SPECIAL REPORT: Can the Philippine economy outgrow debt by 2028? (1)

-

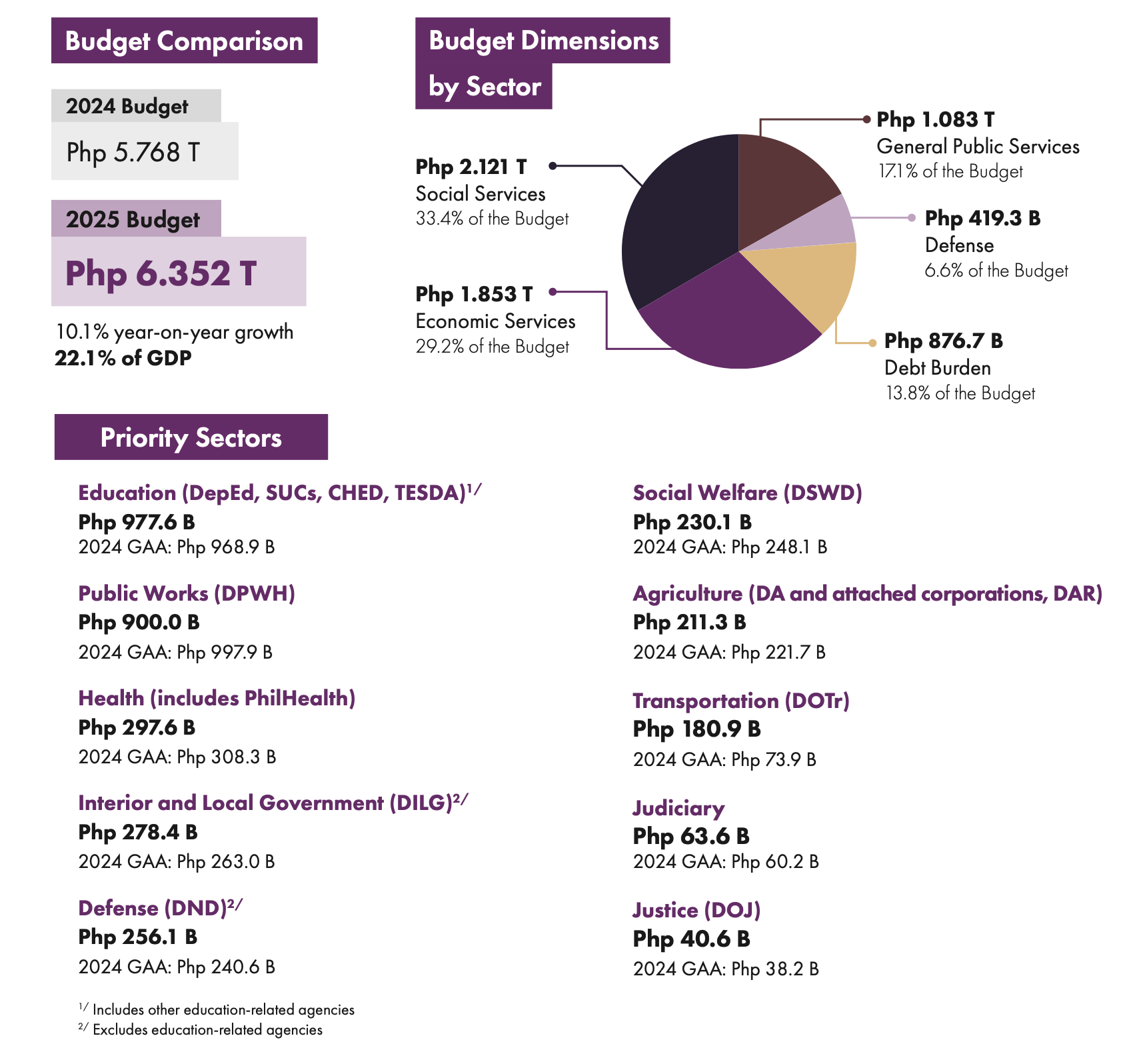

- (First of three parts) The Marcos administration is asking Congress for a P6.352 trillion national budget for 2025, which is a 10.1 percent increase from the current P5.768 trillion government budget. However, a larger budget results in higher debt levels since the government doesn’t have enough revenues to fund its planned expenditures. To maintain operations and grow the economy, the government runs a budget deficit, but is it sustainable?

The country’s ballooning national debt stands at P15.48 trillion by the end of June 2024, representing a 9.4 percent increase from P14.15 trillion during the same period in 2023. In the first half of 2024, the ratio of debt to GDP was 60.9 percent, while the proposed budget would be 22.1 percent of GDP.

Next year, the government needs more money to pay off its maturing debts. Taxpayers will cough up P876.7 billion for debt payments, or 13.8 percent of the 2025 budget.

The lion’s share of the Department of Budget and Management’s (DBM) spending priority will go to social services (P2.121 trillion or 33.4 percent of the budget) and economic services (P1.853 trillion or 29.2 percent), for a total of 62.6 percent. The rest will go to general public services (P1.083 trillion or 17.1 percent), defense (P419.3 billion or 6.6 percent), and debt burden (P876.7 billion or 13.8 percent).

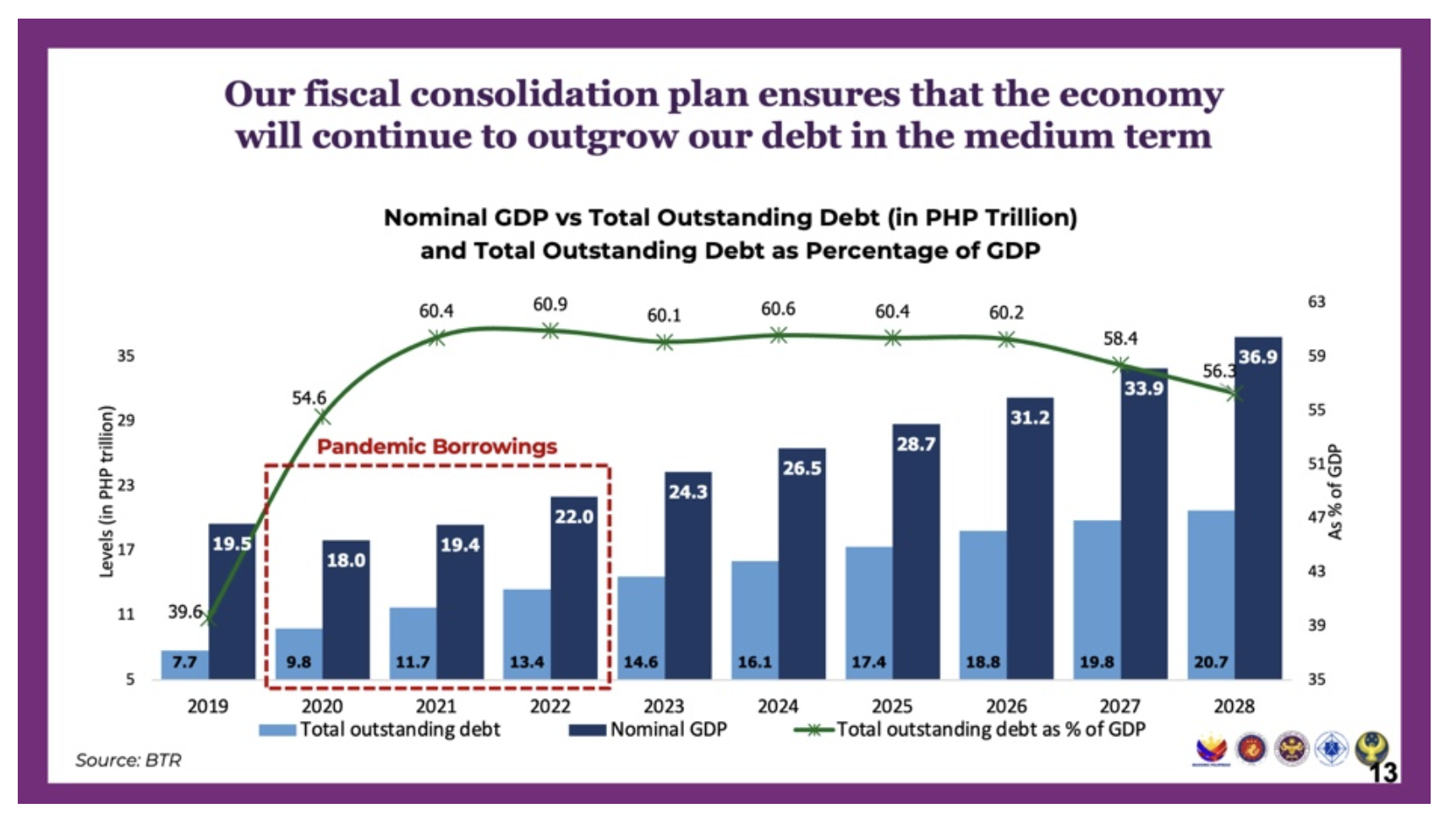

Pandemic spending coupled with a paralyzed economy in 2020 through 2021 resulted in a total debt of P13.4 trillion in 2022, the year in which President Rodrigo Duterte’s term ended and President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s administration began. Research by Inquirer.net puts the government’s outstanding debt at P12.79 trillion in mid-2022.

Sen. Grace Poe, chair of the Senate finance committee, has pledged that senators will scrutinize the government’s spending program “as guardians of the public purse.” Poe warned that the Marcos administration’s “borrow, borrow, borrow” strategy should be an exception rather than the norm, as the bigger the debt, the higher the interest to be paid.

Read more: Maturing COVID loans push PH debt to limit: Did we benefit?

Is the Philippine government capable of managing an ever-increasing annual national budget that only leads to higher debt levels?

This question is timely given the budget season that started this month. The House of Representatives has started committee hearings on the proposed budget bill for next year that contains the expenditure program of the government. The Senate met with the Development Budget Coordination Committee (DBCC) two weeks ago and is conducting parallel hearings while waiting for the budget bill, which is now being scrutinized by the House.

Chaired by Budget Sec. Amenah Pangandaman, the DBCC is composed of the secretaries of four member agencies: DBM, NEDA, Department of Finance (DOF) and the Office of the President (OP). Their duties include resource allocation and management (DBM), revenue generation and debt management (DOF), overall macroeconomic policy (NEDA), and presidential oversight (OP). The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas serves as a resource institution responsible for monetary measures and policies.

At the DBCC briefing, Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Arsenio Balisacan told senators that increased government spending would be necessary to achieve the Marcos administration’s goal to transform the Philippines into an upper-middle-class country by 2025, although he admitted that this goal may not be unlikely by next year.

According to the World Bank, the Philippines is classified as a country in the lower middle-income bracket with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita of $4,230 in 2023, an increase from the previous year’s $3,950. The Marcos administration has set a goal of reaching the upper middle-income status for the Philippines by next year. But the World Bank has raised the upper-middle income status threshold from $4,516 to $14,005, making this goal more challenging.

Balisacan is the director general of the National Economic Development Authority, which is the country’s primary socioeconomic planning body. Despite the high inflation that the country faced in 2023 and early this year, Balisacan revealed that the DBCC has maintained a growth target of 6.0-7.0 for 2024 and 6.5-7.5 for 2025. For the period between 2026 and the final year of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s term in 2028, DBCC has set an ambitious goal of 6.5-8.0.

“Given the latest GDP outturn of 6.3 percent in the second quarter, the economy needs to grow by at least 6.0 percent in the second half of the year to meet the low-end growth target of 6.0 percent for 2024,” said Balisacan. He stressed that meeting the low growth target “will keep the country on track to becoming an upper middle-income country by 2025, provided that the other macroeconomic targets are also achieved.”

For this to happen, the average foreign exchange rate should not exceed Php58 to US$1. The exchange rate has since gone down to Php56.44 to the U.S. dollar (as of Aug. 22).

“For so long as we don’t exceed Php58 per dollar next year for the exchange rate, among the other indicators, we expect to hit or to be reclassified as an upper-middle income country. Otherwise, reaching the upper-middle class status could be delayed to 2026,” said the secretary.

Debt-to-GDP ratio

Budget Secretary Amenah Pangandaman told reporters on July 29 that the increased debt servicing was mainly due to maturing government loans during the COVID-19 pandemic and the depreciation of the peso.

The debt-to-GDP ratio is a metric that compares a country’s public debt to its GDP, and in the case of the Philippines, it indicates the government’s ability to pay off its debt.

“Generally, government debt as a percent of GDP is used by investors to measure a country’s ability to make future payments on its own debt, thus affecting the country borrowing costs and government bond yields,” said Trading Economics (tradingeconomics.com) which tracks historical data and economic forecasts for 196 countries.

Trading Economics estimates that the country’s debt to GDP averaged 55.54 per cent from 1990 to 2023, or from the last two years of the Corazon Aquino administration to the first two years of Ferdinand Marcos’ administration. The ratio reached “an all-time high” of 74.90 percent of GDP in 1993 (Ramos administration) and a record low of 39.60 percent of GDP in 2019 (Duterte administration), it said.

But by the end of the Duterte administration, the national debt grew to P13.4 trillion, more than double the P4.6 trillion debt incurred by Benigno Aquino III’s administration or close to the combined debt stock of the Benigno Aquino and Arroyo administrations (a total of 14 trillion). From the P367 billion incurred by the administration of Marcos Sr. that lasted for 20 years, the national debt has reached P15.48 trillion to date.

The government’s economic team is not concerned about the consequences of using more borrowing to fund government expenses. While the total debt today stands at around P15 trillion, the size of the economy is P26.5 trillion, said Finance Secretary Ralph Recto during the DBCC briefing.

Recto isn’t as concerned about the ballooning debt because of the Philippines’ strong economic fundamentals. Last year, the country saw the fastest GDP growth in Southeast Asia. He expects the pace of economic growth to outpace the debt level, even if it reaches P20 trillion by 2028, because the size of the economy could expand to P37 trillion.

At the DBCC briefing, Recto presented a graph that shows the government’s fiscal consolidation plan. He urged the lawmakers to use the debt-to-GDP metric instead of simply considering the actual outstanding debt. “Based on the chart, although it appears that our debt continues to increase, our economy is also growing. It only means that we can pay our (maturing loan) obligations,” said Recto, explaining that from 60.9 percent in 2022, the debt level went down to 60.1 percent in 2023.

“And we are determined to continue pushing it below 60 percent, so we have enough buffer in case another crisis hits us. And to be clear, there is nothing inherently wrong with a country having debts … as long as the money is used for the right purposes such as growing the economy, which in turn, creates more jobs, increases income, and provides more revenues for the government; and … as long as the government has the ability to repay these obligations without compromising on other essential projects,” Recto said.

The government is using debts “to spur our stronger economic recovery by investing in more infrastructure and human capital development projects, which have the highest multiplier effect on the economy,” he stressed.

‘Borrow, borrow, borrow’ strategy

Sought for comment, Senator Poe observed that the proposed budget “suggests the administration’s effort to keep our debt profile in the median of comparable countries in the ASEAN while still being able to fund the various public services and projects for the coming year.” ASEAN stands for the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations that includes the Philippines.

The current debt-to-GDP ratio of 60 percent is well within the internationally accepted threshold of 70 percent, consistent with the DBCC projections, according to Poe.

“While the planned P2.545 trillion gross borrowings feel like it is not any better than the previous years, this is expected as the government really operates in a fiscal deficit. Our economic managers claim that this ‘borrow, borrow, borrow’ strategy is necessary and advisable for as long as our nominal GDP, which is currently at P26.5 trillion, is still growing faster than our total debt which is at P15 trillion,” Poe said.

She, however, cautioned economic managers against being too reliant on debt, as it could limit the Marcos administration’s fiscal capacity in the event of economic shocks, both internal and external.

“That said, as guardians of the public purse, we (lawmakers) issue a reminder that debt must always be an exception rather than the norm. We must remember that the bigger the debt, the higher the interest to be paid. This could limit our ability to respond to unforeseen economic challenges or invest in other critical areas,” she stressed.

For Poe, the government should start recalibrating its “heavy borrowing mindset” amid the government’s deficit spending strategy that is becoming worrisome to lawmakers and taxpayers.

Poe hit the nail on the head when she called on the government to focus on lowering the debt level by, logically, increasing its revenue generation capacity.

“We always need to recalibrate our fiscal strategies by relying less on borrowing and focusing on sustainable revenue generation for the government. Our fiscal managers are on the right path as they reported a 15.6 percent growth in revenues. We can only hope that this upward trend in revenue lends a hand to our national debt policies,” she said.

The senator expects the government to use debt as intended–“to spur economic growth and encourage investment in infrastructure and human capital that have a positive multiplier impact on our economy.”

“The 2025 budget, as proposed, shows fiscal prudence but there is always room for improvement. Throughout the budget scrutiny process, we will demand more from our economic managers and agencies to show us why all that debt is worth it,” she added.

(To be continued)

Take a look at the second part of this special report.