Navalny believed he would die in prison — memoir

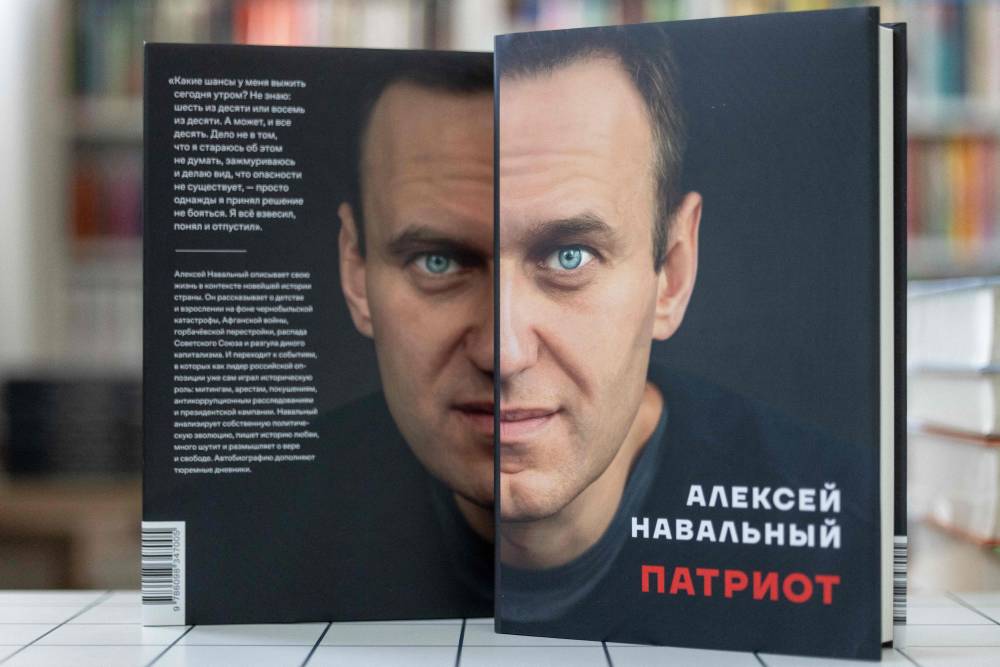

PARIS –A much-awaited posthumous memoir by Russian dissident Alexei Navalny was published worldwide on Tuesday, containing sometimes humorous descriptions of his life including his time in prison and the now-famous prediction that he expected to die there.

Navalny, the top opponent of Russian President Vladimir Putin, began writing “Patriot: A Memoir” after his near-fatal poisoning in 2020.

The book recounts his youth, activism, personal life and his fight against Putin’s increasingly authoritarian hold on Russia.

Navalny worked on the manuscript and diaries that form the basis of the book until his death, aged 47, eight months ago.

US magazine The New Yorker and The Times of Britain published excerpts from the book earlier this month, including Navalny’s chilling expectation of his own death.

“I will spend the rest of my life in prison and die here,” he wrote on March 22, 2022.

“There will not be anybody to say goodbye to… All anniversaries will be celebrated without me. I’ll never see my grandchildren.”

‘Gang of liars’

Navalny had been serving a 19-year prison sentence on “extremism” charges in an Arctic penal colony.

His death on Feb. 16 at age 47 drew widespread condemnation, with many blaming Putin.

Navalny was arrested in January 2021 upon returning to Russia after suffering major health problems from being poisoned in 2020.

“The only thing we should fear is that we will surrender our homeland to be plundered by a gang of liars, thieves, and hypocrites,” he wrote on January 17, 2022.

In a lucid, and sometimes lighthearted, tone Navalny also talks about matters far from politics or activism, such as his taste for cartoons, and the love for his wife, Yulia Navalnaya.

He also describes the drudgery, and pointlessness of daily prison routines: “At work, you sit for seven hours at the sewing machine on a stool below knee height,” he wrote.

“After work, you continue to sit for a few hours on a wooden bench under a portrait of Putin. This is called ‘disciplinary activity.'”

Looking back at his childhood, Navalny remembered that the absence of chewing gum in the Soviet Union seemed to him to indicate his country’s inferiority on the world stage.

After the breakup of the Soviet Union, Navalny the student observed the corruption among university professors and the wealth grab by oligarchs in the new Russia.

Whatever hope he may have put in post-Soviet Russia’s political elite evaporated with Boris Yeltsin, whom he calls a drunk surrounded by thugs, and Dmitry Medvedev, president between 2008 and 2012, whom he calls both corrupt and stupid.

Navalny said he hated Putin, not only because he targeted him personally, but also because he thought the president had deprived Russia of two decades of development.

‘Cheery stoicism’

In an entry dated Jan. 17, 2024, Navalny responds to the question put to him by his fellow inmates and prison guards: why did he come back to Russia?

“I don’t want to give up my country or betray it. If your convictions mean something, you must be prepared to stand up for them and make sacrifices if necessary,” he said.

In the Arctic colony where he was sent in December 2023, walks longer than half an hour were impossible because of the bitter cold, Navalny writes.

On Feb. 16, 2024, he was declared dead, under unclear circumstances.

“‘Patriot’ reveals less about Navalny’s politics than it does about his fundamental decency, his wry sense of humor and his (mostly) cheery stoicism under conditions that would flatten a lesser person,” the New York Times said.

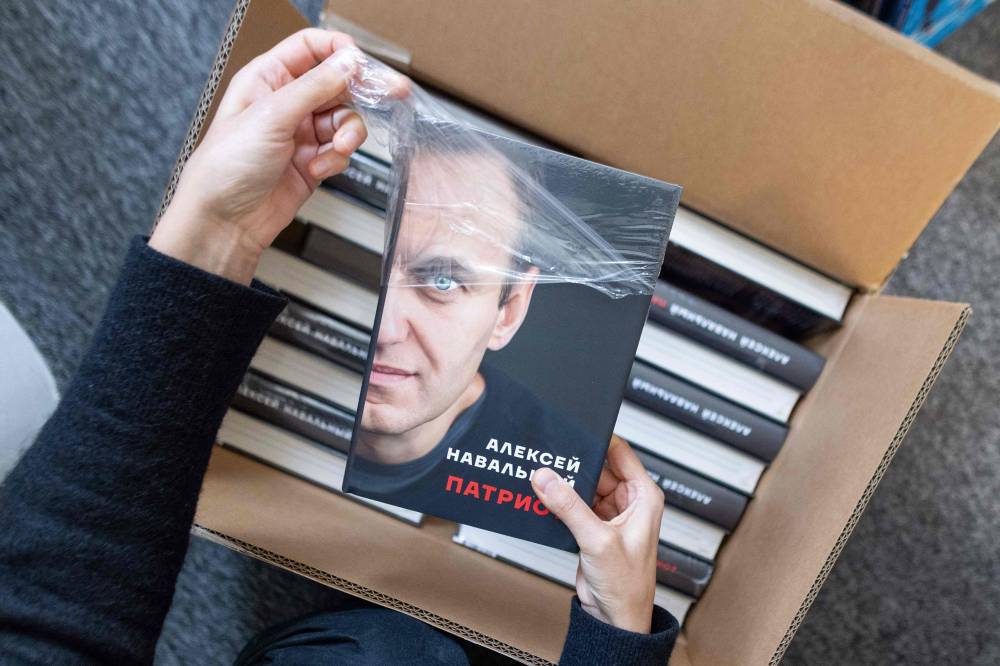

“It is important to publish these kinds of books,” said Caroline Babulle, at the book’s French publishers Robert Laffont, which has printed a first run of 60,000 copies.

“Patriot,” which had a worldwide run of several hundred thousand copies, topped Amazon.com’s list of bestselling books on Tuesday. It’s not available in Russia.

Mix of indifference, curiosity

In Moscow, there was a mix of indifference and curiosity Navalny’s autobiography was published on Tuesday.

Outside the house in Moscow where Navalny lived with his wife Yulia and two children, several former neighbors shrugged at the news.

Valentina, a 60-year-old nurse, said she was “not very interested” by the life of Navalny.

Anna, 39, an economist, also said she was “not very interested” by the anti-corruption activist and lawyer, who Amnesty International described as “a prisoner of conscience jailed only for speaking out against a repressive government.”

He had “no role in my life”, Anna said.

“Why should I be interested in this book since I know everything already?” Natalia, a 66-year-old pensioner, told AFP after throwing out some rubbish near the apartment building.

But others were much keener to know more about Navalny, who led massive demonstrations against Putin before he was jailed on a string of successive charges, widely seen as repeated punishment for challenging the Kremlin.

Outside the entrance to the home where Navalny lived from 2000 until 2010, 58-year-old Tamara shared a happy of memory of when they would walk their dogs together in the neighborhood.

“I knew he was an opposition leader but I never got into the detail,” she said with a smile, setting down two heavy bags to speak to AFP.

“His death saddens me on a human level.”

Elena, 41, said the Navalny couple were “positive, polite and nice people who joked a lot.”

“Our children went to the same school and loved to stroke their bulldog,” she said, adding that she would read the autobiography if possible.

AFP is one of the world's three major news agencies, and the only European one. Its mission is to provide rapid, comprehensive, impartial and verified coverage of the news and issues that shape our daily lives.