Policing the police: Reformation through the PNP Patrol Plan

- (Last of three parts)

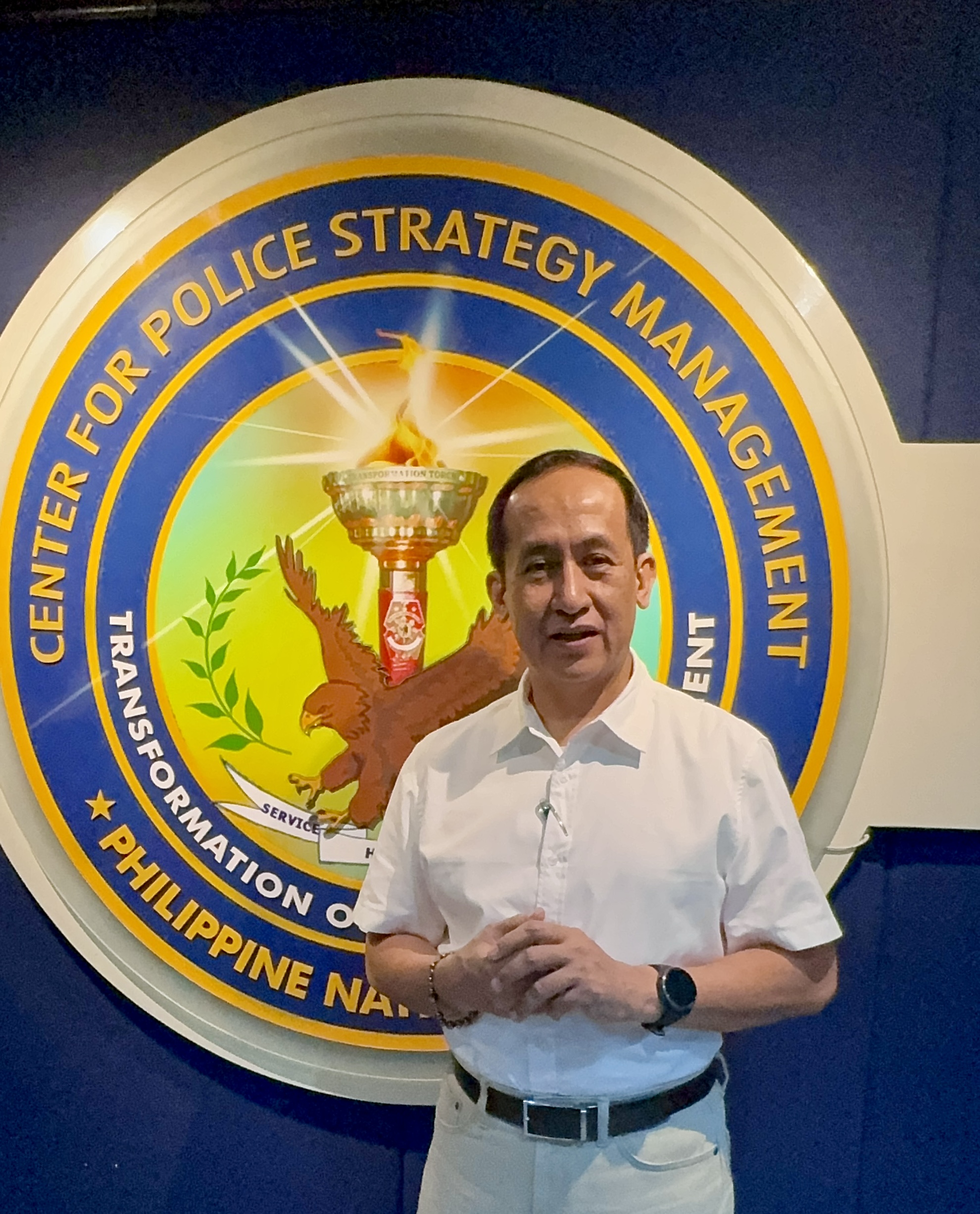

Transformation has been the overarching goal of the “PNP P.A.T.R.O.L. Plan 2030,” which stands for “Peace and Order Agenda for Transformation and Upholding the Rule of Law.” The long-term strategic framework aims to transform the Philippine National Police (PNP) into a highly capable, effective and credible institution by the year 2030.

But can this goal be achieved in six years?

The question has taken on a greater significance after former Police Cols. Royina Garma, Edilberto Leonardo, and Lt. Col. Jovie Espenido testified before Congress implicating several top police officers in extrajudicial killings committed during President Rodrigo Duterte’s brutal war on drugs.

Garma and Leonardo were themselves implicated in the killings of retired Gen. Wesley Barayuga in 2020 and the three Chinese inmates at the Davao penal farm in 2016. The two retired colonels, who are known to be close to Duterte, were named by confessed hit man Arturo Lascañas as key figures in the Davao Death Squad in the latter’s affidavit submitted to the International Criminal Court, which is investigating the Duterte drug war killings.

Dysfunctions

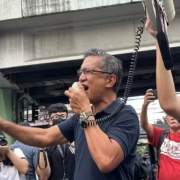

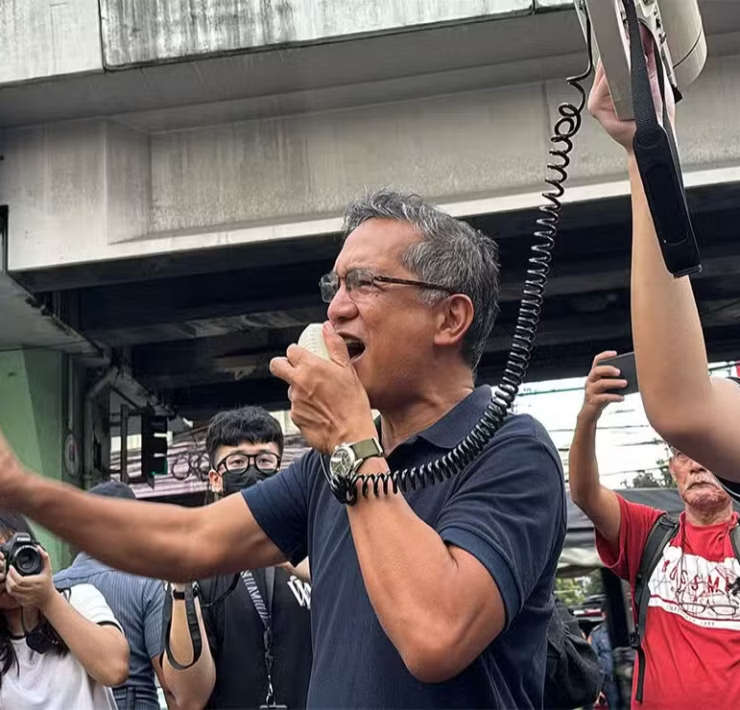

“The problem of the PNP is cyclical,” disclosed former Police Brig. General Noel A. Baraceros, one of the architects of the Patrol Plan whose career in the PNP was largely spent shepherding the plan’s implementation from its inception. He is still the driving force behind the reform movement in the police force even though he retired in 2019.

Baraceros sat down for an interview with the Inquirer Mobile last week to shed light on the progress—and continuing challenges—of the reform movement in the PNP that started right at the rebirth of the police force in 1991. Back then, he disclosed that the PNP was being hounded by the same “dysfunctions” in personnel placements and promotions, as well as corruption committed by police officers.

Baraceros recalled that in 1992, the newly elected President, Fidel V. Ramos, implemented a top-to-bottom revamp of the PNP to rid it of scalawags. That was just the second year of the PNP, having separated itself from its military roots, the defunct Philippine Constabulary-Integrated National Police, a year prior through Republic Act No. 6975.

The PNP’s mandate is derived from RA 6975 (as amended), which is to “enforce the law, prevent and control crimes, maintain peace and order, and ensure public safety and internal security with the active support of the community.”

But because of observed organizational weaknesses, dysfunctions and threats (amid rising crimes in the 1990s and early 2000s), various programs were introduced to reform the PNP right at its inception.

There were significant accomplishments, but it became “apparent that the PNP was in need of a transformation plan that is more long-term and holistic in character,” according to a briefer on “Transformational Journey of the PNP.” The briefer was earlier provided by the PNP Center for Police Strategy Management (CPSM), where Baraceros served first as deputy director and then director from 2011 to 2019.

Integrated Transformation Program

Thus, the PNP Integrated Transformation Program (ITP) was born in 2005, featuring 34 components to resolve the dysfunctions and improve the quality of police services, among other notable objectives.

The PNP-ITP is the final output of three important documents—the PNP Reform Commission Report chaired by former Justice Sec. and Ambassador Sedfrey A. Ordonez, the joint study conducted by the national government and the United Nations Development Program, and the third study conducted by the Supreme Court and the PNP itself.

The PNP-ITP also had 20 priority projects, including the model police station project, public information and advocacy, the PNP shelter program, healthcare system, legal assistance, strengthening the training system, upgrading the crime laboratory and information and communications infrastructure, and improving the retirement and pension systems.

Also in 2005, the PNP Program Management Office (PMO), which was the precursor of CPSM, was created to function as the think tank and central management facility for PNP-ITP projects. Baraceros served in various capacities in the PMO from 2008 to 2010, rising to become its chief of staff before becoming deputy chief of the PNP Public Information Office.

ITP was supposed to be a 10-year program from 2005 to 2015, but halfway through that time, in 2009, the PMO conducted a survey and analysis of the implementation of the program. Only 30 percent of the 34 components were completed. The leadership then decided to upgrade the vision from “more capable to highly capable (police service) by 2030,” recalled Baraceros.

Performance Governance System

The need to comply with the Millennium Challenge Corporation’s criteria for financial grant for the country in 2009 and the PNP-ITP assessment conducted in 2010 in collaboration with the Development Academy of the Philippines, accelerated the change agenda. This paved the way for the institutionalization of the Performance Governance System (PGS) at the PNP and five other government agencies during the Macapagal-Arroyo administration.

With the introduction of the PGS, the Patrol Plan came into being. Bereft of its complexities, the Patro Plan simply envisions a two-pronged outcome: enhanced police capability and a safer community.

To achieve this, the PNP came up with a 20-year-vision vision to become “a highly capable, effective, and credible police service working in partnership with a responsible community towards the attainment of a safer place to live, work, and do business,” according to the plan’s roadmap.

“What one (PNP chief) is doing will become a building block for the next Chief PNP. This is the first time that we have a long-term strategy, a 20-year program,” he said. Baraceros added that the national government at the time recognized that the PNP could easily implement PGS because of its existing Integrated Transformation Program.

“The most important is that the national government saw that the PNP is an agency that has close contact with the communities, and their presence is very important,” he said.

In simpler terms, for the PNP to become highly capable, its officers need to be fully equipped; to be competent, the police must have sufficient training to prevent and solve crimes effectively; and to be credible, they must gain the trust of the people by working to improve the image and service reputation of the police.

Useful strategic management tools

Baraceros explained that it was through the PGS that the PNP “learned to utilize useful strategic management tools to analyze its internal and external environment, and assess the continuing responsiveness of its systems and processes.” These tools include stakeholder analysis, SWOT analysis, gap analysis, strategic shifts, and value chain analysis.

Thus, through the use of these tools and the PGS, the PNP was able to create its own charter statement, road map, and balanced scorecard, he said.

The Patrol Plan is aligned with the Philippine Development Plan and other national government priorities, and it emphasizes enhancing law enforcement capabilities, maintaining peace and order, and strengthening the rule of law.

It should be noted that PGS is the heart of the change agenda, as the Patrol Plan is based on this framework. “[It] aims for transparent, accountable, and results-based governance” by using a “balanced scorecard approach to measure the performance of police units and personnel,” according to the Patrol Plan briefer.

Resource management (optimization), learning and growth (enhancing competence, motivation, values, discipline), and process excellence (where crime prevention and solution, and human rights-based policing are rated) are all part of the strategy roadmap. All of these are geared toward creating a community that is a safer place to live, work, and do business.

According to Baraceros, the PGS addresses corruption, political and economic stability, and human rights through adherence to the rule of law.

The Patrol Plan has led to actual reforms in the PNP budget system, such as the bottom-up participatory budgeting process and the decentralization of funding distribution, and the modernization of the logistical resources of the police service, which include police cars, watercraft, and aircraft. For instance, from a baseline of 67 percent and 31 percent in 2010, the provision of firearms and investigative equipment increased to 105 percent and 60 percent, respectively, in 2019.

PNP Scorecard

The scorecard is also a game-changer in all these reform efforts, as PGS subjects police officers to a quarterly review of their performance, which includes accomplishments, competence, and integrity, instead of using loyalty alone as a basis for promotions and re-assignments.

Specifically, the PNP scorecard operationalizes the strategy map through objective-setting, measures or key performance indicators, targets and actual accomplishments, and initiatives (i.e., programs, projects, and activities). For instance, the objective (desired outcome) of crime prevention is only achieved by reducing crime volume. Measures consist of conducting patrols, neutralizing criminals, and maintaining police community relations.

Thus, at the time the PNP’s PGS was certified as institutionalized in 2019, “the dysfunctions identified in 2005 … have either been addressed or have shown considerable improvement. The PNP now has optimized use of limited resources, sufficient government funding resulting in adequate resources for programmed activities, decentralized funding distribution, sufficient logistical support given to police stations, and sufficient fill-up in basic logistical resources,” the CPSM briefer stated.

Challenges

One major challenge with the scorecard is the reporting requirement (monthly for operations review and quarterly strategy review). With the police already facing significant paperwork for their investigations and after-operation reports, reducing paperwork for PGS-related compliance and monitoring reports can increase compliance by the police officers.

Since 2010, the PNP has embarked on a continuous training and performance-based audit of its compliance with its mandate. This has been a process of reverse engineering of sorts, in which the organization has sought to analyze its strengths and weaknesses, as well as gain insights into its systems and processes, to determine what works and what doesn’t.

The PNP is likewise constantly fine-tuning the roadmap due to police-related issues hogging the limelight and constant feedback from the public, including the formation of civilian-led Advisory Groups (AGs) in every police unit or office.

However, not all senior police officers and their subordinates have fully embraced the PGS.

For PGS to succeed, it “requires the buy-in and contributions” of members of the PNP, according to Baraceros.

He pointed out the necessity of individual police units from national, regional and local levels to comply with their scorecards and pursue goals and objectives that are aligned with their mother units, so that these contribute to the success of the entire command group, for instance.

Using the scorecard to gauge the performance and success rates of the police will also reduce corruption because it requires accountability from the police. Thus, there are PNP members who are still reluctant to embrace PGS “because of what it asks of them,” he said, referring to the objectives, measurable performance indicators, targets and actual accomplishments contained in the PGS scorecard.

“PGS is basically performance. It looks at the results of what we do and what we want is transformative. From individual, personality-based, we want to strengthen our institutions, specifically the PNP,” he said.

The retired general noted that in the experience of the United Nations, “all those countries that fail—and I hope we don’t become failures—they (nations) fail because the first one that is lost is the trust of the people in the police.”

And then there is the issue of the fast turnover of the PNP leadership, especially every time a new PNP chief is appointed. Baraceros cited the case of the late PNP Chief Camilo Cascolan, who served for only two months in 2020 as the head of the police service.

“From a short-term (perspective), what we want is a long-term program, said Baraceros.

Advisory Groups

The PGS is a participatory process, so it observes good governance by involving all sectors of society.

AGs are present in all levels of the PNP organizational structure—local and national—from the national administrative units (e.g., logistics support service) and operational support units (e.g., Maritime Group, Intelligence Group) to the 17 Police Regional Offices, and various police provincial and city police offices nationwide.

The AGs task is to bridge the divide between law enforcers and the communities around the country, besides increasing their competencies as law enforcers through various training programs conducted for free by AGs.

The goal is for the PNP to become a “more effective, responsive and credible force,” with the AGs partnership with the PNP hopefully enhancing trust between the police force and the public. If carried out to its logical, righteous conclusion, the Patrol Plan through the PGS can help in “enhancing law enforcement capabilities, maintaining peace and order, and strengthening the rule of law,” said Baraceros.

Conclusion

The involvement of some PNP members, including ranking officials, in high crimes and associations with unsavory characters in politics and the underworld, cannot be swept under the rug. This has been well-documented recently by the House of Representatives and the Senate in their parallel investigations into the links between the Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators, extrajudicial killings and war on drugs.

Thus, the Patrol Plan is the first solid attempt at a holistic reform of the PNP that uses individual unit scorecards and particularly involves the civilian populace through the AGs, which help rate the police officers’ performance scorecards through the PGS.

Baraceros said that peace and order cannot be detached from its context.

Previously, we only looked at peace and order. But we should also look at whether the police have the resources. Are our police officers well-trained? Are … promotions, benefits given to them because we need to motivate them to (maintain) high morale, so they can perform their job (well),” he said.

He stressed that the police should only focus on crime prevention and solution, not engage in other distractions that deviate from their core mission.

Finally, what would restore people’s trust in the PNP is the continued and increasing partnership with the communities through the AGs, a total buy-in of the transformation agenda through the Patrol Plan, strict implementation of discipline for errant officers, and certainty of punishment even for ranking officers.

“We should fast-track what we’re doing. The (leadership) should not lose focus but (continue to be) in support of the overall objective of the transformation program of the Patrol Plan, which should (even) be enhanced,” said Baraceros.