Passing down the art of spaces and structures

Interior design, construction, and architecture are often a family affair, where the wisdom and expertise of the elders are passed down to the next generation like heirlooms.

The visionaries showcase how tradition, innovation, and a deep sense of identity shape their craft. Their philosophies and passion inspire a new generation to design with purpose, lead with ingenuity, and create with heart.

Here are stories of families whose legacies are etched in interiors, structures, and spaces. From timeless design philosophies to groundbreaking innovations, these trailblazers prove that artistry and craftsmanship can transcend generations and shape the future of their industries.

Nena and Tito Villanueva

Interior designers

Like most senior designers, Elvira “Nena” Ocampo Villanueva would often impart wisdom to her son, Tito.

“A true designer doesn’t rely solely on a limited color palette. Some get stuck in the beige, black, white, and brown formula. A good designer knows how to mix colors effectively. Secondly, a designer should always consider the client’s personality and preferences. Imposing one’s own taste can lead to generic, impersonal spaces. Lastly, while interpreting the client’s vision, a designer should also educate them about interior design principles,” said Tito, recalling the advice he got from his mom.

Nena studied interior design at the Universidad de Madrid and the New York School of Interior Design.

“Her style was traditionally Spanish—dark woods, heavy moldings, stones, and earth tones. Yet, she wasn’t afraid to incorporate bold accent colors. A room might be predominantly neutral, but a pop of turquoise could add a vibrant touch,” Tito explained. “The clean lines, solid colors, and geometry of the Bauhaus style was believed to be suitable for the office.”

When Tito experimented with metal frames, his mother suggested they were more suitable for a den than a living room.

“Today, we might consider that old-fashioned,” admitted Tito, whose style bridges the gap between traditional and contemporary.

“I avoid excessive curves and ornamentation. My goal is timeless design. Projects I completed 20 years ago still look relevant today,” he said. One of his techniques involves taking inspiration from the lines of historical furniture, streamlining them for modern lifestyles, and enlivening them with contemporary fabrics and colors.

Tito is known for his skillful blending of colors. One of his notable projects is the Magsaysay Room at the President’s Guest House. He used a custom pistachio color by Boysen to highlight hand-painted nature murals, a nod to Ramon Magsaysay’s farming roots. The four-poster bed features a modern stainless steel frame with a classic headboard. The classical round-backed chairs are modernized with contemporary upholstery, and pink pillows add a vibrant contrast to the cool tones.

“During my mother’s time, houses and condos were more spacious. Today, we must be creative in maximizing small spaces and incorporating storage solutions,” Tito said.

He observes that the increasing number of interior designers reflects the growing demand from homeowners who want to personalize their studios and one-bedroom units.

“Social media, vlogs, and lifestyle shows have inspired people to dream big. However, achieving their desired look without professional help can be challenging.”

He and other senior designers believe the younger generation should cultivate a refined aesthetic and apply their knowledge to their own lives.

“While it may sound elitist, clients often hire designers based on their lifestyle and taste. They want to see how elegantly you curate your space. A keen eye for detail and a broader understanding of lifestyle, including entertaining, are essential,” he said. “In my mother’s time, the Philippine Institute of Interior Designers screened licensed applicants based on their lifestyle. Today, the membership seems to be more on numbers.”

He added that many young interior designers start as draftsmen in offices and struggle to establish independent practices. “Due to stiff competition, only a few of the younger generation can rise to the top of the heap.”

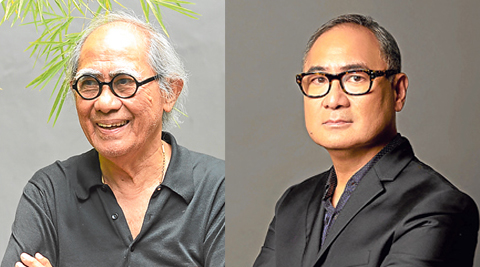

Pablo and Jose Paolo Calma

Builders

Construction magnate Pablo Calma often took his two sons, Jose Paolo “JP” and Juan Carlo, to his construction sites.

Pablo founded Multi-Development and Construction Corp. (MDCC), one of the country’s largest builders specializing in interior projects, particularly in the hospitality industry. Under Pablo’s leadership, MDCC undertook prestigious projects such as the Peninsula Manila, Shangri-la Properties, and Clark International Airport.

JP, who started working at MDCC at age of 16, eventually rose to the position of CEO. A highlight of his career was working on the country’s largest casinos: New Coast Hotel Manila and Okada Manila.

“These two projects pushed the boundaries of executive imagination and required meticulous attention to detail and rapid construction timelines. The lesson: Deadlines are always looming, and quality standards are constantly evolving,” he said.

“Construction sites are chaotic, filled with sweat, labor, and challenges. Achieving high-quality standards in such an environment is difficult, given human limitations and manual labor,” JP added. “I learned from my father the importance of meticulous attention to detail and not simply delegating tasks.”

Disrupting the traditional homebuilding industry, the younger Calma launched Home Qube. This innovative platform leverages blockchain and AI to revolutionize the home design and construction process, enabling users to collaborate seamlessly with a network of experts to realize their dream homes.

He is currently a doctoral candidate at Purdue University, researching Generative Intelligence for the Built Environment with System Engineering applications.

“While MDCC operates in a business-to-business model, Home Qube will cater to individual consumers. It’s like ordering food online. With the high level of personalization and design complexity, no two homes will be exactly the same,” he said.

JP explained that construction is heavily reliant on manual labor, making it challenging to manage large workforces due to human idiosyncrasies. He cited the importance of strong leadership in motivating and problem-solving for such a large team.

However, with the advent of new technologies, he is shifting towards prefabrication, reducing the need for manual labor and enabling the production of more complex home designs.

“If there’s any wisdom to be passed on to the next generation, it’s about how to solve problems. Know-how can be easily acquired, and new technology can easily disrupt past knowledge. What endures is the timeless wisdom of leadership—the character to tackle operational problems with surprising certainty, faith, and heuristics,” said JP.

As a young man, JP admired Depa Group, a leading interior construction and manufacturing firm, and was particularly inspired by their yacht designs. Now, he’s turning his admiration into action by building his own vessels.

JP finds yacht building a more refined and less production-intensive process compared to traditional construction. He’s developed a passion for composite materials, particularly GFRP and carbon fiber. In fact, he’s already made history by completing the first-ever carbon fiber Kevlar hull in the Philippines, a 14-meter landing craft cargo boat.

Francisco and Miguel Angelo Mañosa

Architects

Growing up with Francisco “Bobby” Mañosa, Gelo witnessed his father’s nationalism manifest in the experimentation of local materials and the advancement of Filipino craftsmanship. Dubbed the Father of Neovernacular Filipino architecture, Bobby used the bahay kubo as the criteria for his designs to establish cultural identity. The Coconut Palace, Amanpulo, and Pearl Farm Resort embody this design philosophy.

While studying Design Science at the University of Sydney, Gelo encountered green architecture, then known as climate-conscious architecture.

The elder Mañosa’s philosophy—architecture must be true to its land and people—brought modernity to tradition. Gelo recognized his wisdom as he learned the science behind the bahay kubo: the pitched roof accommodating warm and wet seasons, the large windows facilitating cool air and energy efficiency, the weather protection of native window awnings, and the use of available materials.

“The house was purely organic,” said Gelo. “The cultural fundamentals of the bahay kubo paved the way to a tropical climate-conscious house.”

In building structures, Gelo studies the sun path, wind dynamics, and heat-absorbing properties of materials and colors.

Understanding the science behind the Filipino architectural vernacular enables him to design with practicality, not just aesthetics. “The building will be cooler. The wind will penetrate the house quicker. The thermal comfort in the rooms will work well, and the high ceiling will let the hot air rise, cooling the room,” he said.

“Growing up, I lived in a bubble influenced by my dad’s philosophy of designing Filipino. As a student and young architect, I worked only for his firm which I now manage. It has been my entire world,” he added.

As CEO of Mañosa & Partners, he reminds his team to keep evolving. “We wake up every day with the aim to showcase Philippine architecture to the world.”

Gelo is concerned about the increasing trend of “Pinterest architecture” or designs based on social media images. “Some architects no longer look to their roots for design inspiration. Many are mere copycats or variations of copycats, or even rely on AI-generated design ideas,” he observed.

As a result, architecture is beginning to look homogeneous. Technology can accelerate the design process, but it can also hinder critical thinking. Clients’ demands for faster and cheaper designs often lead to shortcuts.

Gelo envisions elevating climate-conscious architecture while remaining rooted in Filipino culture. He explores other cultural references, such as the Chocolate Hills, for design inspiration. His current project, a bridge for Bridgetowne inspired by the sea dragon, pays homage to the Filipino-Chinese heritage of developer Robinsons Land.

“AI can reshape the architectural landscape. However, we remain committed to bespoke design and cultural authenticity,” Gelo said.

Lor and Ed Calma

Architects

Architect Lorenzo “Lor” Calma, a proponent of modernism in the Philippines, believed in the power of surprise, integrating fine arts, site planning, landscape, and lighting into every space.

His minimalist approach, combined with attention to materiality and craftsmanship, elevated the design.

Lor seamlessly blended local materials, culture, and craft into his work, rooting his designs in their specific context. His versatility is unparalleled, spanning architecture, interiors, furniture, art, sculpture, and jewelry. He was also one of the pioneers in professionalizing the interior design industry.

One of his stunning works is the Angara family chapel in Baler. “He was 85 then. He took a sheet of metal, bent it and said, ‘This is the chapel,’” recalled his son Eduardo, or Ed to friends.

“He didn’t rely on his previous works, which were boxy, white, and minimalist. He’s not fixed into a certain style. He would design according to the context. That chapel was in a big field surrounded by trees.”

Ed, a leading Philippine modernist architect, is renowned for his unique spatial typologies. His designs integrate modern aesthetics with the site’s natural character. By prioritizing site analysis and capturing its essence, he creates spaces that evoke introspection and resonate with the spirit.

One of his interesting works is an upcoming retail building along Tagaytay Road. The four-level edifice is characterized by curves on each floor, abstracting the undulating terrain. The landscaped roof will only be visible from the street. As one draws near, the entire building is revealed.

Ed said his father explained his design process to him but never imposed it on his son. He wanted Ed to develop his own methods and critiqued his designs after seeing them. This parenting-mentorship style is passed on to his daughter Daniella, a project architect for the prestigious Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM). Like Ed, she graduated from Pratt Institute and received a scholarship from Yale Graduate School.

“I didn’t even influence her to be an architect. It takes a certain character to be one. Daniella has got it in her. She wouldn’t be satisfied after finishing something. She would go back and redo it,” Ed said.

As the managing partner, principal architect/designer of Lor Calma & Partners, he is assigning her to design a vacation home in Calaca, Batulao, where she can learn to work in the Philippine context—dealing with small-scale projects, limited lot sizes, and local materials.

The three generations of architects carry the value of continuous improvement. At 97, Lor continues to sketch, reflecting on his past projects and re-evaluating them.

“Daniella is still starting. I want her to go out of our sphere of influence and create her own things. It’s boring if you continue the same work for three generations with no change. That would be boring. If she could come up with something new,” said Ed.