They turned Baguio into a university town

BAGUIO CITY—Lawyer Paolo Salvosa remembers listening to his grandfather, Benjamin, talk about his philosophy that “education is a right” when he was a child.

The 39-year-old Salvosa shared that he lost his grandfather at the age of 9, but a piece of wisdom from the family’s elders has stayed with him ever since.

He now works as a strategic management consultant for the family-owned University of the Cordilleras (UC). The institution, originally named Baguio Colleges, was founded in 1946 by the late Benjamin Salvosa. It was renamed Baguio Colleges Foundation in 1966 and achieved university status in 2003.

Peter Rey Bautista, 56, fondly recalls similar memories of his grandfather, Fernando Bautista, who, together with his wife Rosa, established what is now the University of Baguio (UB) in 1948.

“Finding new opportunities in this city, my lolo (grandfather), who was a teacher, quickly packed up their belongings and journeyed from Tondo with Lola, who was pregnant with my father (Reinaldo Sr.), my then 2-year-old uncle Fernando Jr., and a baby who was uncle Benjamin (he became an architect),” said Peter Rey, a former Baguio mayor.

Two city streets below City Hall are named after these men (Fernando G. Bautista Drive and Benjamin R. Salvosa Drive) for helping shape education in the city.

Baguio hosts the century-old Teacher’s Camp, where the country’s public school system was developed by the American colonial government. The city itself was designed, built and opened in 1909 by the Americans.

Nearly every resident of Baguio has, at some point, been connected to UC, UB or Saint Louis University—the latter established in 1911 by the Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (CICM) as a school for boys.

Collaborators

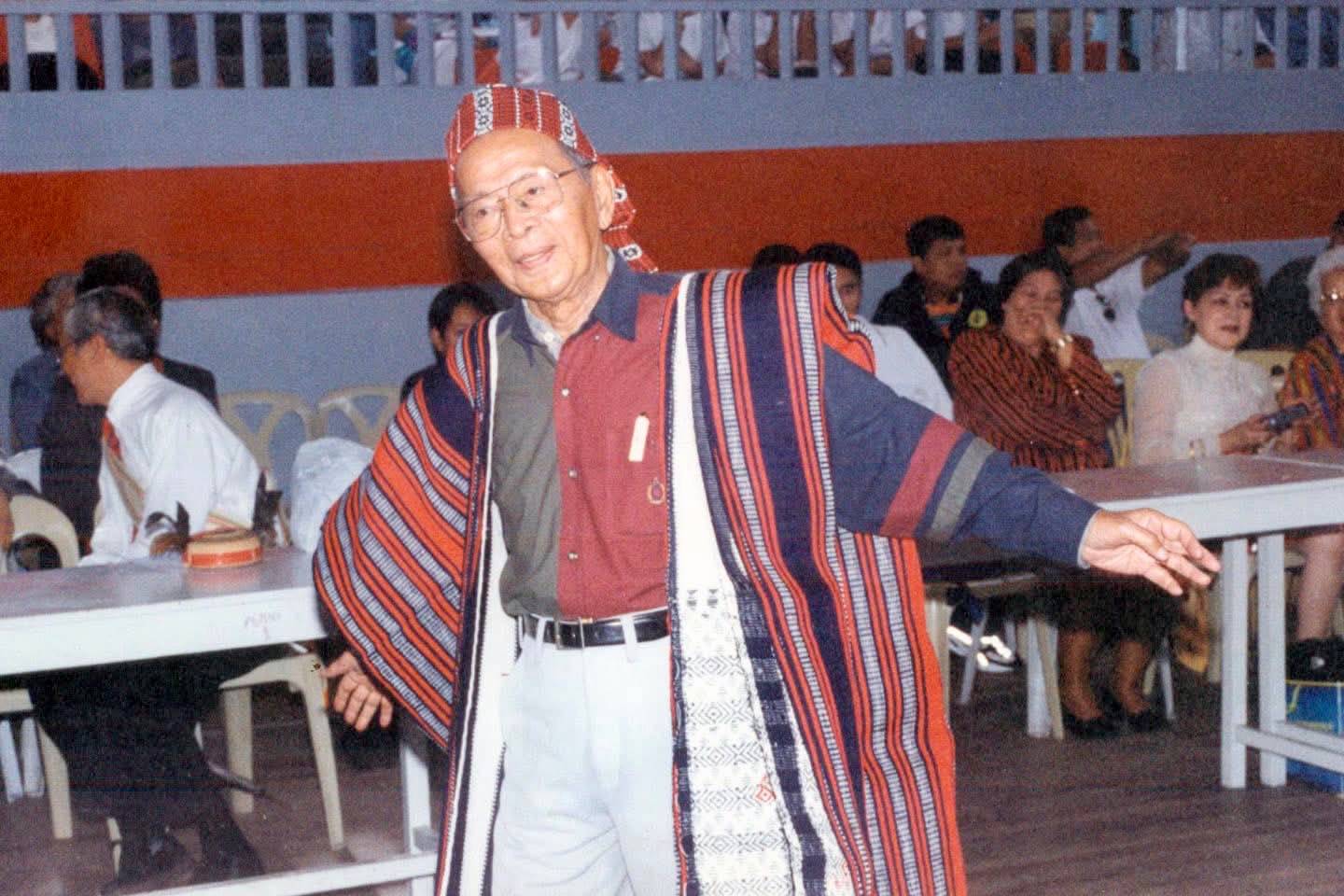

The older Salvosa, affectionately known as “Daddy Ben” to friends, and the older Bautista, lovingly called “Tatay” by his family and employees, began as collaborators with a shared vision of transforming Baguio into a university town.

Together, they established Baguio Colleges, the city’s first post-war educational institution, with Bautista serving as the “industrial partner,” according to Peter Rey.

To accommodate over 100 students, they leased buildings along downtown Session Road.

Bautista later established Baguio Tech, officially known as the Baguio Technical and Commercial Institute, starting with just 80 students. Over time, it grew and evolved into what is now UB.

Their children took on the responsibility of running these schools.

Reinaldo Sr. and his brothers alternated serving as presidents of UB, while Paolo’s father, Ray Dean, and his siblings served as presidents, chairs or members of the board of trustees at UC.

The torch was eventually passed to their respective grandchildren, including Paolo, Peter Rey, and their brothers and cousins, ensuring the family legacy in education continued to thrive.

Paolo said Benjamin, a lawyer, strove to build a “school for the poor,” triggered in part by the desolation and destruction left by the war and the struggles and sacrifices required to rebuild Baguio. Only the Baguio Cathedral was left standing after the Americans “carpet-bombed” the city in March 1945 during its liberation from the invading Imperial Japanese Army, which had retreated here.

Paolo said Baguio Colleges and its later incarnations shouldered the cost of many scholarships for the underprivileged. But it also offered new and attractive programs apt for the times, like law in the 1950s.

‘Practical academia’

Peter Rey believes Baguio Tech was the true spirit of “practical academia” that “Tatay” had in mind when he entered the education business.

“UB now has countless disciplines, but I think the school he wanted was rooted in the technical and vocational courses Baguio Tech first taught. I want to bring that back,” he said, although he has not taken an active role in running UB.

The two universities were set back by two calamities: the 1990 Luzon earthquake that required Baguio to again rebuild from the rubble and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, which crippled many businesses and forced college students to leave the city.

Paolo said the high demand for nurses helped UC recover when enrollment in its nursing and other health-oriented programs spiked. Both universities now take in about 20,000 students yearly, with UC operating a trimester.

But the demographics have since changed from students coming from neighboring Cordillera and Ilocos towns to the young digital natives, Paolo said.

Skilled talents

During the Regional ICT Summit and Exhibition held here on Nov. 28, UC revealed that it was among the Cordillera universities which improved their courses in information and communication technology (ICT) to help increase skilled “talents” as digital companies look to the provinces.

Mark Allen Rabago, talent development manager of the IT and Business Process Outsourcing Association of the Philippines, said the industry needed graduates trained in new IT specializations because IT firms had advanced from providing call center services to digital health services as well as digital entertainment.

Rabago said companies engaged in creative services had become the fastest-growing sector of the IT trade. Digital businesses engaged in or ancillary to health services are the booming IT enterprise for Baguio.

In October, UB hosted the two-day Zonal Creativity Summit organized by the Commission on Higher Education, where top universities of northern and central Luzon were encouraged to offer “creative arts curriculums” to increase workers needed by gaming, film and animation companies.

Paolo said UC’s academic community had also been helping improve the curriculum and operations of many state universities in the Cordillera.

These initiatives could expand Benjamin’s vision “from a university town to a university region,” he said.