‘Green Bones’: Hope springs eternal in the most unlikely places

Existing is hard enough; living, harder still.

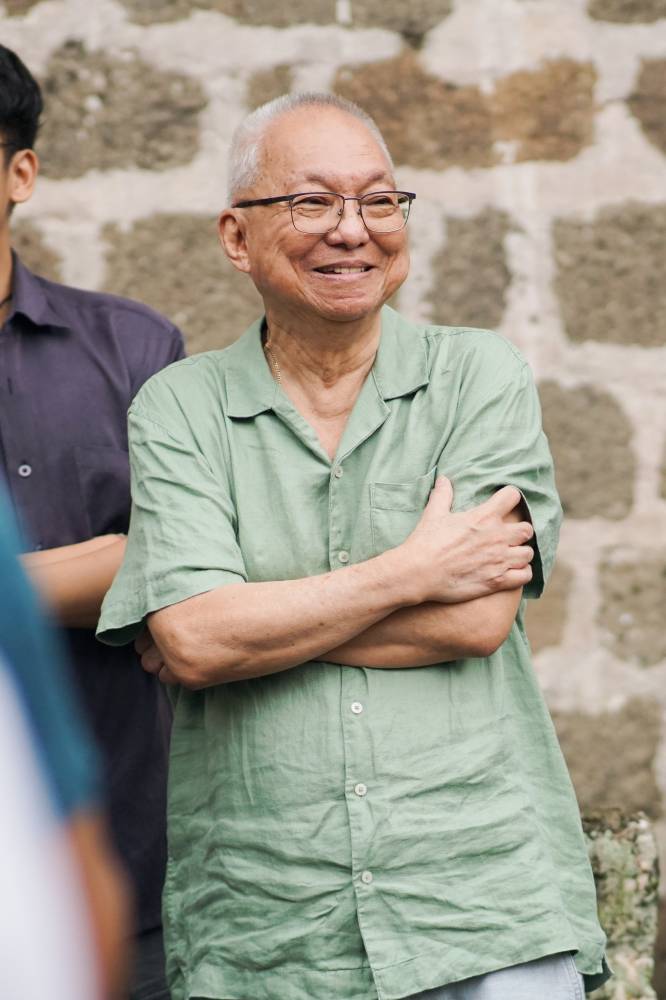

“There’s so much evil around us—and it’s only growing around the world. Sometimes, merely going on social media can already overwhelm us with negativity,” National Artist for Film and Broadcast Arts Ricky Lee told Lifestyle. “Ang dilim ng lahat (Everything is dark)”

And amid blinding darkness, it’s but human nature to search for a beacon—something to hold on to—as we stumble our way through life.

Many find it in religion. Others see hope in the faces of their families or loved ones. And then there are some who are still left wanting, people who find themselves asking for signs, or the tiniest shreds of reassurance that kindness ultimately endures.

Final gift

There’s a relatively unheard-of belief, said to have originated from the Chinese, that finding green bones among cremated remains suggests that the deceased lived a life of goodness. They’re supposedly the departed’s final gift to the bereaved, some of whom turn the fragments into mementos—sources of comfort, and supposedly, good luck.

“When I heard about this long ago from Chinese friends, and friends whose dead parents left them with green bones, the first thing that crossed my mind were my own parents,” Lee said.

His mother died when he was 5; his father followed, just three or four years after. “I lost them so early in life. I had a lot questions. There’s no way to find out now whether they had green bones or not so there’s this tinge of regret that I wouldn’t ever really know.

“But they have green bones, most likely, especially my father whom I got to know better. Ang bait-bait ng tatay ko. And I would like to believe that,” the revered screenwriter said.

But if such earthly remnants are a manifestation of kindness, can they emerge in a place seemingly robbed of light? This idea is the impetus for the drama film “Green Bones”—a 2024 Metro Manila Film Festival (MMFF) entry penned by Lee together with last year’s best screenplay winner Anj Atienza, from a concept by writer-documentarist JC Rubio.

Conflicting characters

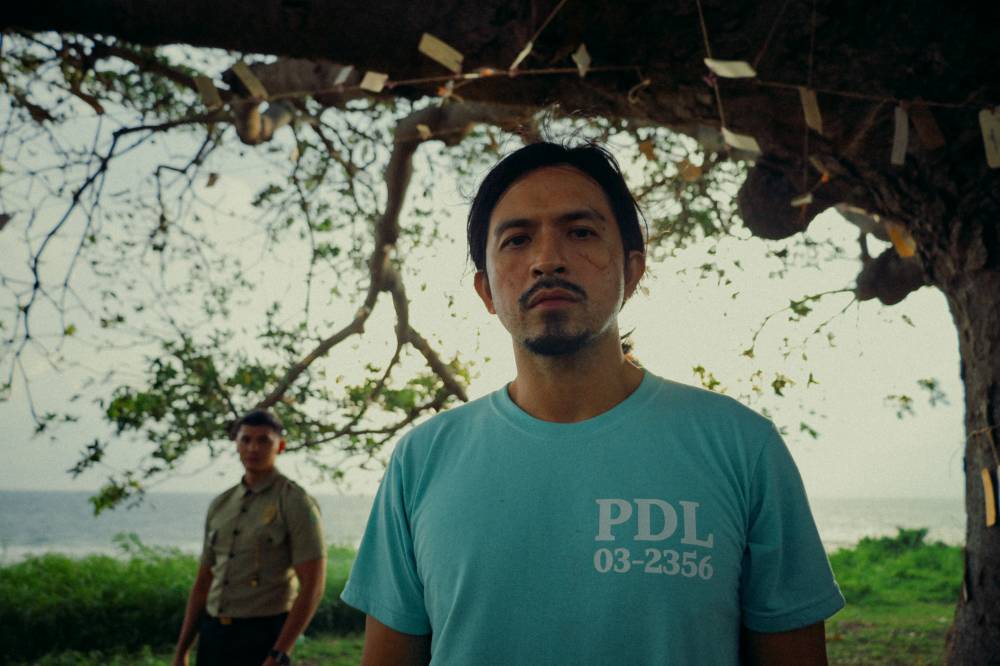

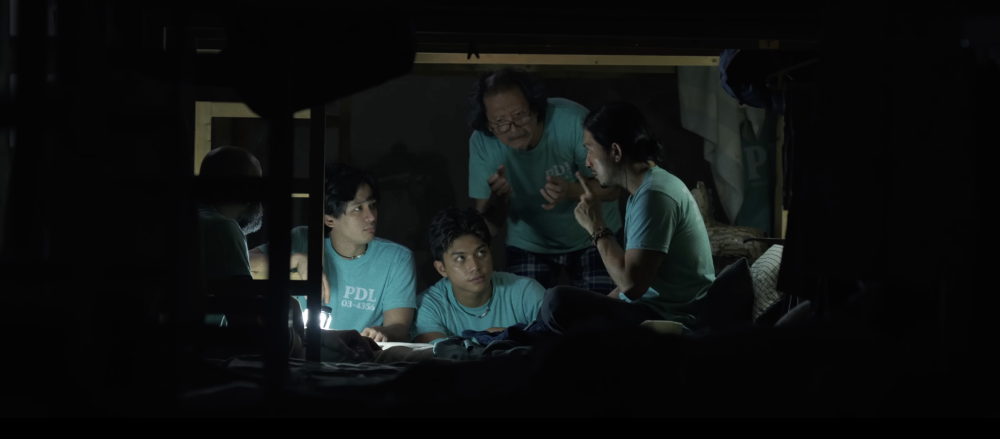

Directed by the award-winning filmmaker Zig Dulay, the film is set in a penal colony and follows two vastly conflicting characters. Domingo Zamora (played by Dennis Trillo) has spent most of his life behind bars for the murder of his own sister. But through the years, he changes for the better, and by all indications, has become a reformed man.

Zamora finds himself eligible for parole. However, his impending release is put in jeopardy by the arrival of Xavier Gonzaga (Ruru Madrid), a young prison guard with a chip on his shoulder. And with him, he carries a vial containing pieces of green bones from his sister, who died a senseless death at the hands of criminals.

To the young warden’s jaded eyes, everything is black and white. All criminals, he believes, are beyond help. Zamora is no exception. Fueled by a noxious cocktail of his melancholy, cynicism and unfounded suspicions, Gonzaga does everything in his power to keep Zamora in prison.

Traumatic pasts

While it can be easy to paint Gonzaga as the hero, and Zamora, the villain, the realities of humans are far more complex than that, Lee pointed out. “They’re adversaries. But soon, they will realize that they’re both prisoners. One is physically trapped behind bars; the other, trapped in his own wrong beliefs,” he said.

“Before long, the two will find out that they’re both held victims by their traumatic pasts, and that they must band together to set each other free,” said Lee, the genius behind the scripts of some of Philippine cinema’s most important films like “Himala,” “Jaguar,” and the feminist trilogy, “Brutal,” “Moral,” and “Karnal.”

At first, the story begs the question: Who among them is good? But digging deeper, the question inevitably turns into something else entirely: What is goodness even to begin with?

“How do we know? Who is in the position to judge? Maybe it’s the laws that dictate whether or not people are bad. But those laws can have holes to them. Or, you can be bad and be on your way to changing your life,” he said.

“At the same time, there are far more evil people outside of prison. Are they good just because they walk among us?”

Road to redemption

If this film is sounding like it will make for a despondent holiday viewing, fret not, Lee said. Christmas, after all, is a season of hope. And while some may be inclined to think that it’s impossible for kindness to sprout from the bloodied soil of a penal colony, or the squalid confines of a jail cell, the contrary is true for Lee—for light shines brightest when it’s darkest.

“I believe that there’s actually more opportunities for kindness amid evil. There will always be someone who will struggle against it. That’s our nature as humans. You will fight, and then we hope that kindness prevails,” he said of the overarching theme of the film, which also touches on the plight of PDLs or persons deprived of liberty.

And it’s with kindness that the road to redemption is paved. “Life is about opportunities to change our lives—to be kind, to be free, to do good. Laging may pag-asa. There’s always a second chance … and a third and a fourth and so on,” he said.

Aside from green bones, a second symbol of hope in the movie stands proud in the form of the “Tree of Hope,” whose majestic branches serve as a haven for handwritten notes on which the PDL’s humble wishes are written.

Symbols

But when it comes down to it, symbols are just that—symbols. It’s us people who assign meaning to them. In fact, the scientific reasoning behind the formation of green bones is far less romantic or inspirational than what the belief claims; a study states that it’s a result of certain metals, like copper or iron, coming in contact with the bones during the cremation process.

But even if you take away the material things from the equation, the hope and faith that we attach to them persist. “It doesn’t matter whether the idea of green bones is scientifically true or not. What’s important is that there are beautiful things we can hold on to. And I don’t think that’s bad. The mere fact of believing, for me, already makes the world a better place,” he said.

And this is something that Rubio—GMA Public Affairs’ senior manager for documentaries—would come to realize while working on the film, whose concept he came up with while ruminating on the death of his father at the relatively young age of 48.

Like Lee’s, Rubio’s loss prompted a difficult question: “Why was my father’s life so short? What was the sense of his life?” he told Lifestyle. And when he heard about what people say about green bones, Rubio, also like Lee, wondered, “Would we have found green bones had we cremated my father’s remains instead?”

Surely, they would have, Rubio would tell himself. His father raised him working two jobs, as a teacher and a tricycle driver. He was generous and compassionate. His father wasn’t a public official, but their home, at one point, “looked like a barangay center,” because of all the people coming in seeking his help.

The question stayed with Rubio for a very long time. But now, with the movie complete and about to be shown, he seemed to have finally found his answer. “I no longer need to know if my father had green bones, because in my heart, I know that he was kind,” he said.