The art of strangers

The figure was both imposing and poignant, combining a riot of textures and references while standing under a neon sign that read “Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere.”

That was the title of the 60th International Art Exhibition organized by La Biennale de Venezia in the beautiful Italian city, held last April 20 to Nov. 24, 2024.

“Refugee Astronaut” pretty much represented the weight of displacement that bore down on many of the world’s homeless and marginalized, banished by war, economic strife, environmental crises, or plain discrimination and hate. Created by British-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare, the life-sized nomadic spacewalker was adorned with fabric, and carried a mesh sack filled with odds and ends.

The work, wrote Sofía Shaula Reeser del Rio in the exhibit notes, had a strong environmental bent, serving as “a cautionary tale on environmental negligence and capitalism, challenging the unsustainable pursuit of perpetual growth.”

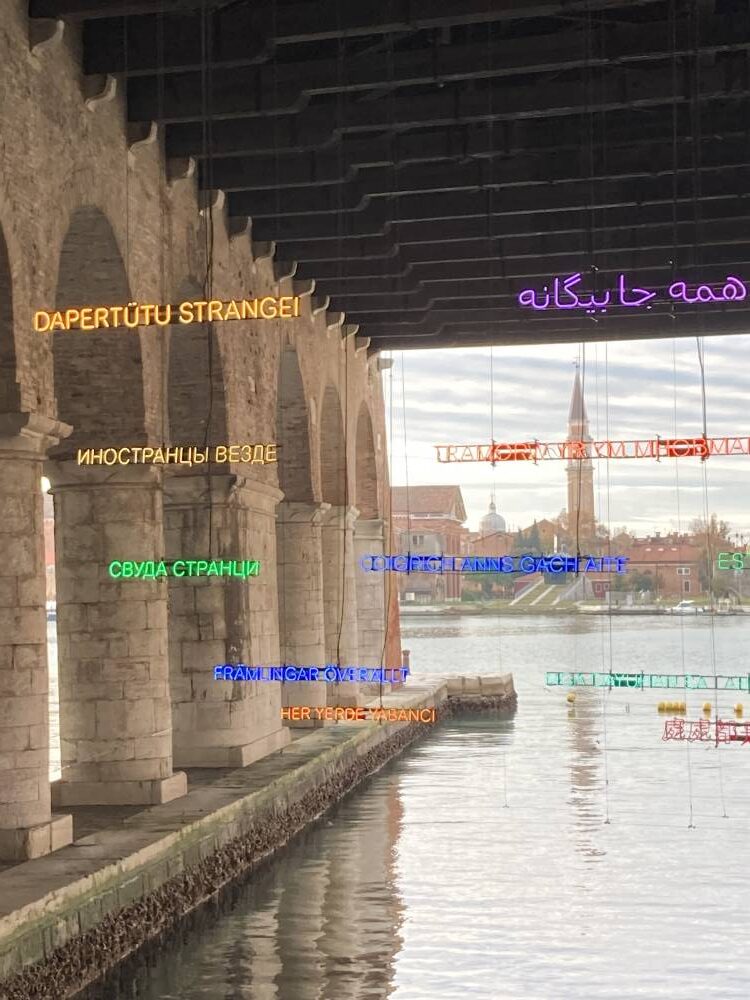

The exhibition title was borrowed from the works of the Palermo, Italy-based feminist collective Claire Fontaine, neon light sculptures spelling the words in different languages, already exhibited in various places and evolving since 2004. The Arsenale incarnation was an outdoor installation, displayed over water, giving it added depth and dimension.

These two works, I thought, were fitting introductions to this massive art exhibition that has been ongoing since 1895, showcasing the newest and best in the art world. The timeliness is evident: “Wherever you go and wherever you are, you will always encounter foreigners,” wrote curator Adriano Pedrosa, artistic director of the São Paulo Museum of Art, in a statement. “… No matter where you find yourself, you are always truly, and deep down inside, a foreigner.”

Sustainability

Since 2021, La Biennale di Venezia has integrated the idea of environmental sustainability in the exhibition, even going for a carbon neutrality certification in 2024. Biennale Arte 2024 also opened up to artists who had never participated in the exhibition. Thus, a dazzling variety of works was seen, from paintings and sculpture to installations, video, and mixed media. By the time the exhibition closed on Nov. 24, some 700,000 people had visited.

This year, the show had two sections: the “Nucleo Contemporaneo” (Contemporary Nucleus) and the “Nucleo Storico” (Historic Nucleus). The titular word “stranger” also translated as artists of every persuasion: queer, outsider, folk, indigenous. The façade of the Central Pavilion, for example, was painted by the Brazilian Mahku Collective with a colorful mural depicting the myth of the alligator bridge, describing how life moved between the Asian and American continents.

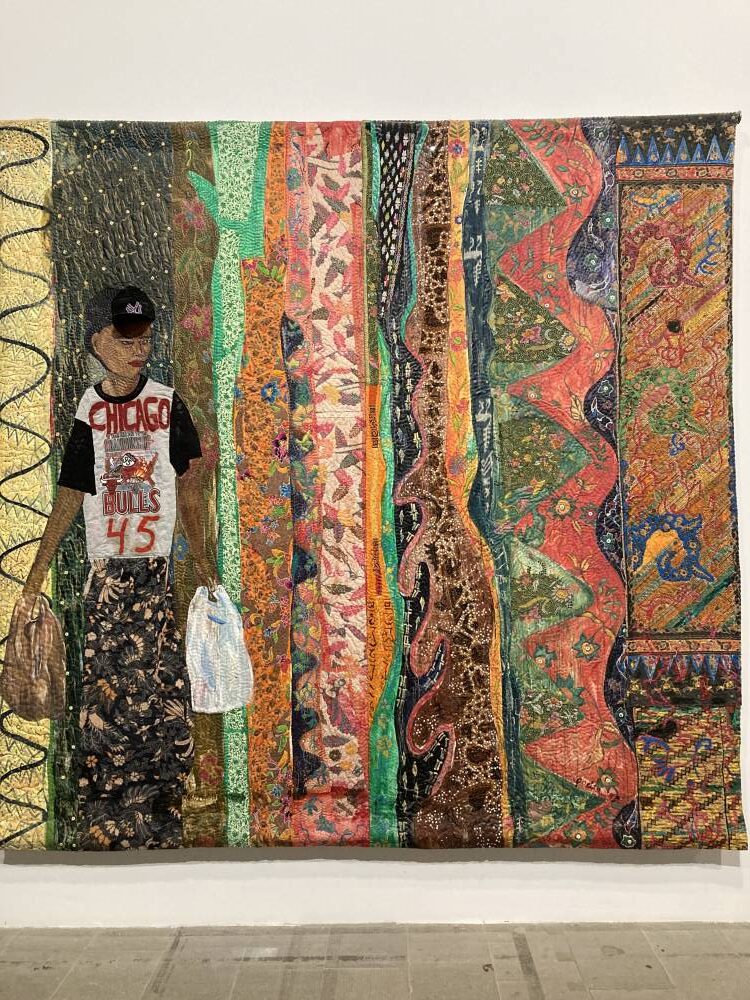

Also in this section: three powerful works by the late Filipina artist Pacita Abad, who specialized in trapunto, or stitching and embellishing stuffed, painted canvases with objects such as buttons and mirrors. Most thought-provoking was her 1995 work “You Have To Blend In Before You Stand Out,” showing a woman dressed in a sarong, a basketball jersey, and a baseball cap, “illustrating the internal struggle that immigrants and their families experience when integrating into a new society,” wrote curator Joselina Cruz.

Other Filipino artists present—all females, incidentally, and like Abad, all first-timers at the Venice Biennale—were Anita Magsaysay-Ho with her 1944 “Self Portrait,” Nena Saguil and her “Untitled (Abstract)” from 1972, and Maria Taniguchi and her “Untitled” from 2023.

Other memorable works: Lebanese artist Omar Mismar’s stunning mosaic showed two men kissing, “Two Unidentified Lovers in A Mirror,” still taboo in his home country—thus, the faces remained an unidentifiable jumble of tiles. Colombia-born Daniel Otero Torres, meanwhile, built an imposing, ephemeral “Aguacero” structure (2024) of collected, recycled materials, a statement on the global water crisis.

Joyful

“Diaspora,” the massive 2024 mural by the Aravani Art Project in Bangalore, a group of women and transwomen, was a joyful, colorful depiction of what could be, if only people of all genders were allowed to be true to themselves.

The Philippines was represented yet again, as Bacolod-born, Belgium-based multimedia artist Joshua Serafin presented a mesmerizing video, “Void,” also an ongoing work. Described as a “queer + trans performance” inspired by the creation of the Philippine archipelago, it showed what seemed like a mystical birthing of a genderless creature drenched in slime. Serafin, incidentally, was just declared one of the Cultural Center of the Philippines’ Thirteen Artists Awardees last December.

At the other venue, the Arsenale, I made a beeline for the 2024 Philippine Pavilion, which showcased the almost serene, thought-provoking work of artist Mark Salvatus as curated by Carlos Quijon Jr., “Sa kabila ng tabing lamang sa panahong ito/Waiting just behind the curtain of this age.” (See previous article in Inquirer Lifestyle, 01/06/24: “Psssst: Serendipity, art, and the road to the Venice Art Biennale.”)

The Philippine participation at the Venice Biennale is a collaborative undertaking of the National Commission for Culture and the Arts, the Department of Foreign Affairs, and the Office of Sen. Loren Legarda.

“Nucleo Storico,” meanwhile, presented portraits, abstractions, and works from the Italian diaspora. Nil Yalter, a French feminist artist based in Paris, featured black-and-white videos of immigrants talking about their difficult lives and heartbreaking struggles, collected from 1977 to 2024, with the title “Exile is a Hard Job” emblazoned in red. Roberto Montenegro (1885-1968), a painter, illustrator, and leading Mexican muralist, contributed a beautiful portrait of a bronzed “Pescador de Mallorca” (1915), capturing the idyll and traditions that antedated any horrors of war.

By contrast, Mexican artist Teresa Margolles, whose works explore the subject of death, showed a rather chilling “Tela Venezuelana” (2019), a human imprint of blood on cloth, obtained after the artist placed the material on the body of a Venezuelan salvage victim.

Color

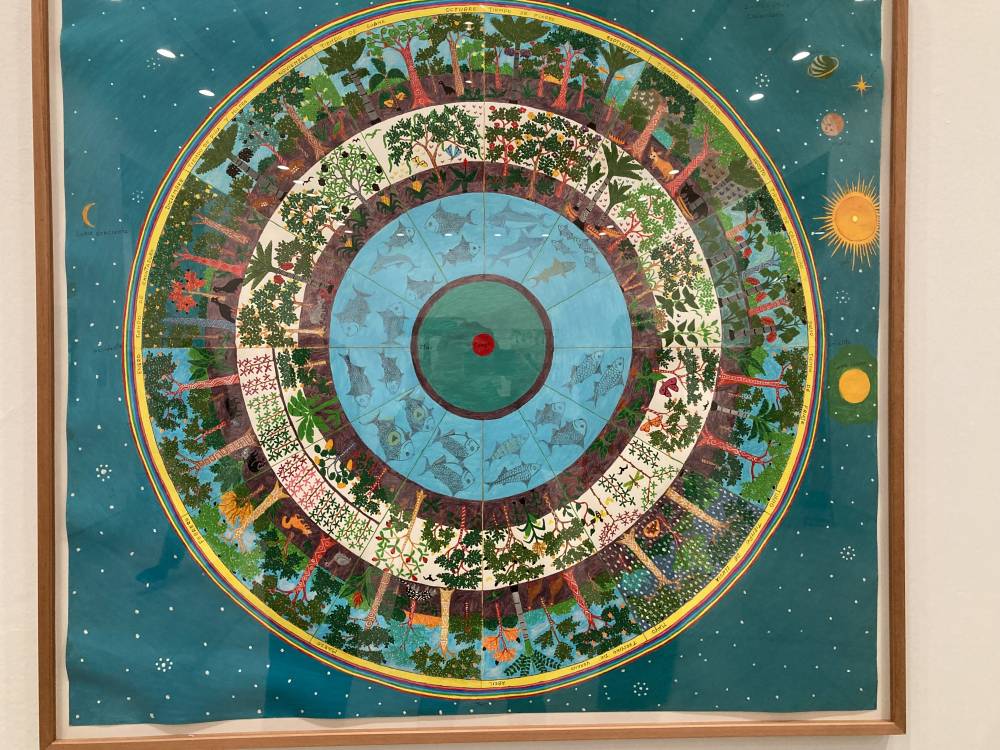

Finally, two versions of how color could be used to send different messages: Swiss artist Aloïse Corbaz (1886-1964), who spent most of her life in a psychiatric hospital and used whatever materials she could find, such as toothpaste and thread, to create surreal, colorful worlds; and Colombian artist Aycoobo (Wilson Rodriguez), whose “Calendario” (2023), a favorite of mine, is a detailed representation of the Amazon forest every month, presenting an indigenous worldview and an exquisite call for environmental preservation.

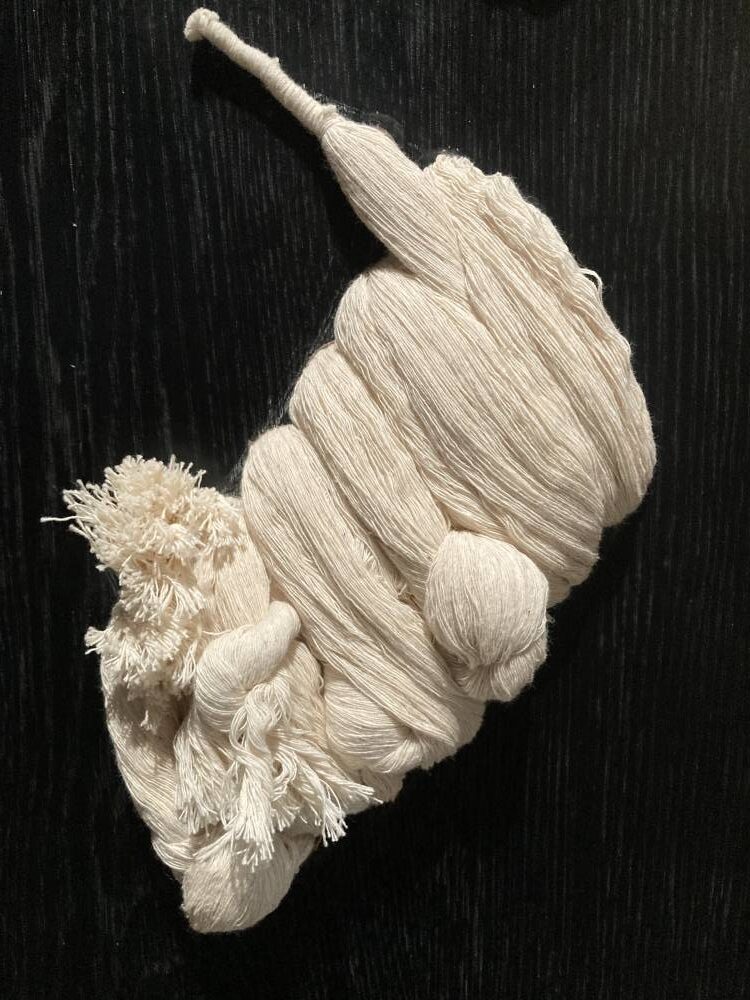

Several national pavilions—there were 86 of them—and more artists provided unique takes on the theme. China’s was called “Atlas: Harmony in Diversity,” and presented a wide range of media and artworks. Most ingenious were Shi Hui, whose delicate “Writing-Non-Writing I: The Eight Principles of Yang” featured knotted cords that captured the essence of calligraphy as well as brush strokes, and Jiao Xingtao, who used leftover copper strips to create figures, and ingeniously animated them on video.

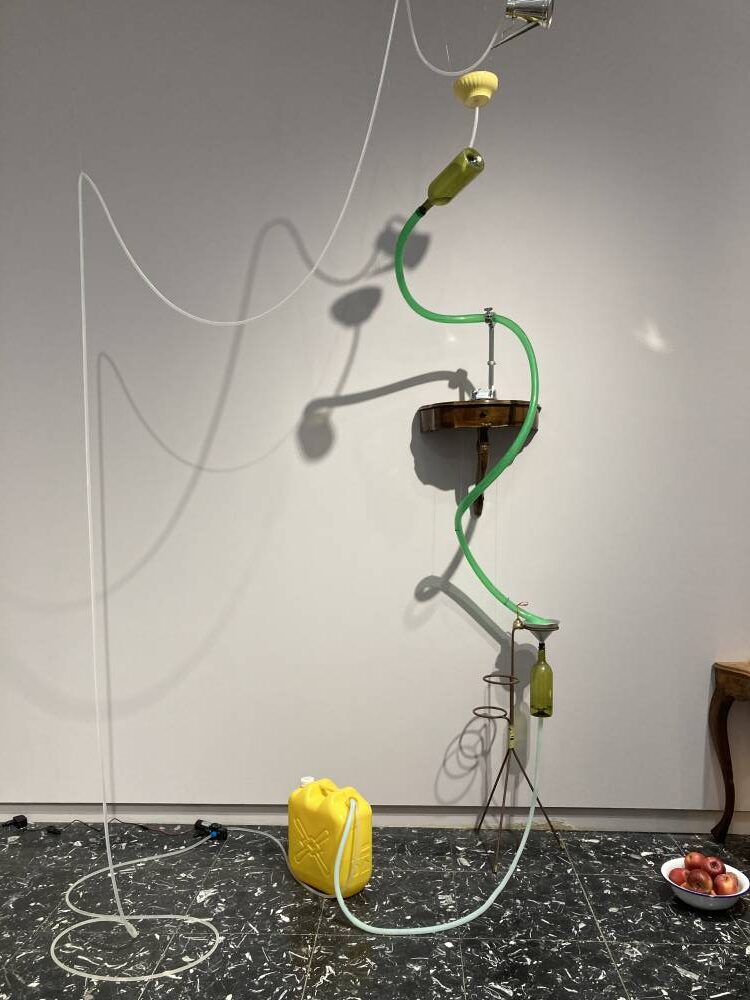

Japanese artist Yuko Mohri’s art in the country’s pavilion, “Compose,” featured seemingly random, almost absurd installations of leaking water and rotting fruit that actually pointed to the environmental crisis and subverted cycles of life. In South Korea’s “Odorama Cities,” artist Koo Jeong A made the statement that “Scent has no borders”—and filled a pavilion with probably the only artworks in the Biennale with an olfactory element. A floating cartoonish figure, balanced precariously on one toe, blew scented smoke into a sunlit space.

Finally, as if to remind us all that art does indeed reflect life and simply cannot exist apart from the world around it, the Israeli Pavilion remained closed and dark, with only a big sign posted on its glass wall. It declared, “The artist and curators of the Israeli pavilion will open the exhibition when a ceasefire and hostage release agreement is reached.”