Nature in a pocket

I had the fortune of growing up in the 1960s in Cubao.

At that time, this now bustling district was more like a suburb. Our modest home was made of wood and had a considerable front yard where my father planted different fruit trees like papaya, dwarf coconut, langka, guava, chesa, kamias, along with some herbs and ornamental plants. The area attracted dragonflies, grasshoppers, butterflies, wasps, birds, spiders, frogs and other critters which we sometimes played with as children.

Our home was, in many ways, organic and it was not unique as our neighbors’ homes were similar to ours.

Consequence of urban growth

That was then. Our old home along with the rest of Cubao is now largely concreted and densified.

The wooden homes have given way to structures made of non-organic, inanimate, and industrialized materials. The old fruit trees are gone, and the insects and birds that visited our small garden have disappeared.

Such is the consequence of urban growth. It is not just the outward spread of cities towards the wilderness, but also of its encroachment inwards, utilizing every available space, eliminating pockets of nature that once existed.

Our urban areas, devoid of the richness of life that flourish in nature, do not benefit from the ecosystem services necessary to support life. Vegetation and forests, in particular, cleanse the air, recharge groundwater, provide habitat for various species of flora and fauna, mitigate floods, regenerate the soil, protect slopes from erosion, provide food, timber, shade, recreation, and well-being.

In place of natural vegetation, we have paved surfaces and in the few areas where greenery exists, we have manicured gardens filled with non-native, exotic species that require higher maintenance, are prone to pests and diseases, and where native birds and insects do not thrive.

Most places in Metro Manila do not satisfy World Health Organization’s recommended universal access to green spaces of at least 0.5 hectare of green space within 300 meters of every home.

Divorced from nature

Urban life has become so divorced from nature that residents of cities flee urban areas to experience nature. This drives tourism that ironically harms forests, mountains, and shorelines, creating a cycle of development, increased visitors, and degradation of pristine natural environments.

Climate change, habitat depletion, and biodiversity loss are among the most severe impacts of society’s fixation on growth. The dilemma is that the march of urbanization remains relentless and the need to create environments for humans remains pressing.

If both urban expansion and nature conservation are equally essential, then perhaps the necessary approach is to re-imbed nature within our urban environments.

Afforestation

Such an approach is possible–done decades ago by countries like Japan.

In the aftermath of World War II, after losing a significant amount of tree cover from bomb raids, Tokyo City created a plan to secure 10 percent of urban lands for green areas and urban parks.

Now one of the densest urban areas in the world, it has 20 percent of its land area devoted to greenery with over 21,000 ha of this green space made up of forest. The approach is called afforestation (creating a forest in an area where no recent tree cover existed) and one of the most promising methods is one developed by Dr. Akira Miyawaki, a plant ecologist, who endeavored to restore native forests in Japan in the 1970s.

Micro urban forests

The Miyawaki method uses the key principles of planting a mix of native species in multiple layers at high density (spacing trees just a few feet apart). It allows for fast growth, about 10 times faster than conventional planting; utilizes small space; and requires little maintenance after a few years.

The combination of deep-rooted trees and plants with shallower, fibrous root systems are effective in holding the soil breaking down harder strata to encourage ground water recharge and preventing soil erosion. This diverse combination helps create a rich ecosystem.

Miyawaki was inspired by the Chinju-no-mori, the ancient pocket forests surrounding Shinto shrines. The method allows for the creation of micro forests within cities that can mature within decades instead of centuries.

Toward biological communities

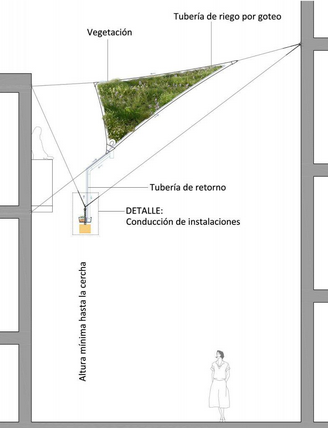

Other places in the world have adopted approaches in re-greening their cities, at times utilizing tiny areas to reestablish nature and rebuild native habitats. Small pockets are being rewilded, parking spaces are being de-paved, roofs and walls are being planted to allow communities to reconnect with nature.

Rebuilding native habitats builds resiliency of our cities. Some experts believe that the recent rise in wild fire frequency in North America could be reduced by restoring native habitats. Plant and animal life are part of systems that support each other and the diversity of genetic material that builds resilience.

Humans have extracted themselves from these systems because of the way we build our cities.

Correcting decades of maldevelopment will be daunting and bringing nature back to its pristine condition may now be impossible. But taking small steps toward achieving balance in our built environment is possible.

The author is a built environment professional and the founder and principal of JLPD, a master planning, architecture and property consultancy. www.jlpdstudio.com