Love and revolt: Reimagining Oryang and Bonifacio’s story

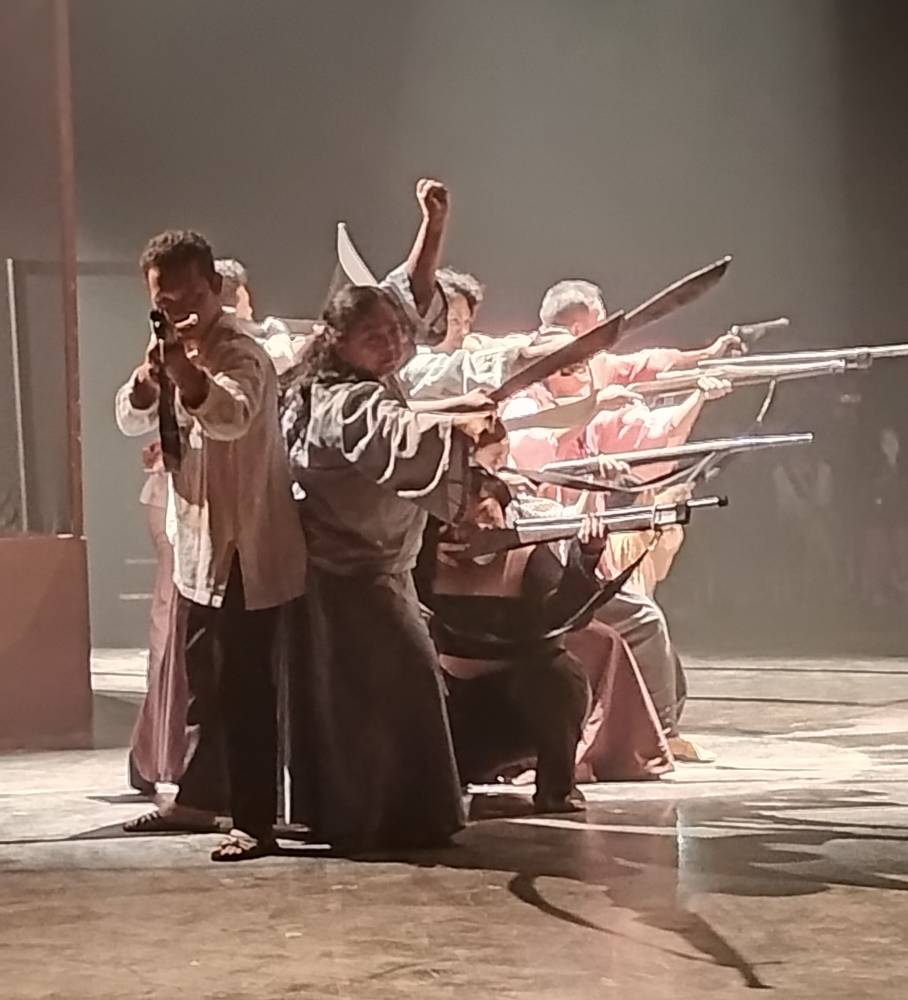

Playwright and cultural activist Bonifacio Ilagan quickly debunks the definition of revolution as an act of terrorism from the get-go of “O, Pag-ibig na Makapangyarihan,” when the spotlight banishes the dark in the Ignacio B. Gimenez Theater.

Ilagan centers his play on the love story of the young Gregoria “Oryang” de Jesus and the revolutionary Andres Bonifacio. He dramatizes the words of historian Teodoro Agoncillo who, in “The Revolt of the Masses,” wrote that it took a plebeian to see the inequality between landed aristocrats and the people mired in poverty and ignorance. Spurred by his love of country and desire for the proletarians to “live and breathe freely,” Bonifacio organized the Katipunan.

“O, Pag-ibig” is Ilagan’s second play to be staged at the Gimenez Theater at the University of the Philippines Diliman after last year’s “Spirit of the Glass.” Premiering in February, it pays homage to two historical events: Oryang’s 150th birth anniversary and the 55th anniversary of the First Quarter Storm of 1970.

The play merges fiction and history and prods Filipinos to think critically in the age of ignorance and naïveté. Ilagan toes the line of creative license and the latitude it gives writers. But he maintains a solid respect for history: At the question-and-answer session after the play on Feb. 22, he explained that the spirited female narrator, the servant Remegia (Angellie Sanoy) is fictional but the play’s idea is based on an extant document—a letter written by Oryang.

The letter, written on Oct. 6, 1893, is kept at the National Archives of the Philippines, according to a Facebook entry by the Caloocan Historical and Cultural Studies Association posted in time for Oryang’s 150th birth anniversary. In the letter to the gobernadorcillo, Oryang detailed her forced separation from Andres.

Two storylines

Ilagan weaves two storylines on love. The first is the love between Oryang (Pau Benitez) and Andres (Nel Estuya) that’s fraught with obstacles stemming from their disparate social classes and the strict rule of marrying within one’s class. Oryang’s mother Baltazara (Astarte Abraham) is against Andres for a slew of reasons: He is a widower much older than the teenaged Oryang, and a seller of canes and paper fans (the last rankles her). Never mind that he is principled, steadfast, and responsible. For Baltazara, marriage is not about love but a perfect alignment of social lineage and wealth, of which Andres is sorely lacking.

Historically, Andres fell hard for Oryang. He visited her at her parents’s house accompanied by Ladislao Diwa and Teodoro Plata, cofounders of the Katipunan. Both play and history books mention Oryang confessing their secret relationship to her father and getting married twice—in a Catholic church and in a Katipunan ritual. Agoncillo wrote that it was Oryang’s father who objected to their relationship because Andres was a Mason, and only relented on the condition they would marry in church.

Significantly, in the play, Ilagan disputes the demonization of revolutionaries. Andres was a revolutionary but he was no degenerate. He was a man born into poverty (and, like other men in love, was nervous, for instance, about meeting Oryang’s parents). He was not a fool and never let his impoverished state hinder his self-improvement or compromise his scruples.

The play portrays Andres Bonifacio as he was in history: an autodidact and an avid reader.

Love of country

Altruistic love is the other storyline in “O, Pag-ibig.” Love and loving in the time of revolution are a luxury for revolutionaries, but Oryang and Andres defy the odds. Their love for each other is strong; they overcome separation and loss (Agoncillo wrote that their firstborn died of smallpox). Importantly, their love is encompassing and grows to include love of country, which strengthens their fight against tyranny.

It’s also in this storyline where Ilagan highlights the gender issue vis-à-vis societal norms. He subverts the Spanish colonial era’s sexist characterization of women as weak and feeble-minded by presenting capable, thinking women like Oryang and the Katipunan members. Oryang stands by Andres’ work and eventually joins the Katipunan.

Historically, Oryang was the vice president of the Katipunan women’s chapter organized mid-1893. Per Agoncillo, the chapter was responsible for recruiting members and, most importantly, safeguarding the male members from surprise raids by the colonial authorities during their meetings. They accomplished this by dancing and singing in the sala in full view of passersby to draw away the suspicion of the authorities.

Ilagan contrasts two women from the same period: Oryang and the servant Remegia. Oryang engages the impressionable servant in a discussion on critical thinking. Remegia serves as an end to a means—Oryang needs her to bring her letter to the gobernadorcillo—but Oryang’s discussion is the first step in cracking Remegia’s ignorance.

Likewise, it’s through Oryang that Ilagan links the past to the present, underscoring the urgency of resisting the distortion of history. Her semi-soliloquy carries a subtle warning against mindlessly believing in trolls and influencers espousing distortions of history as truth.

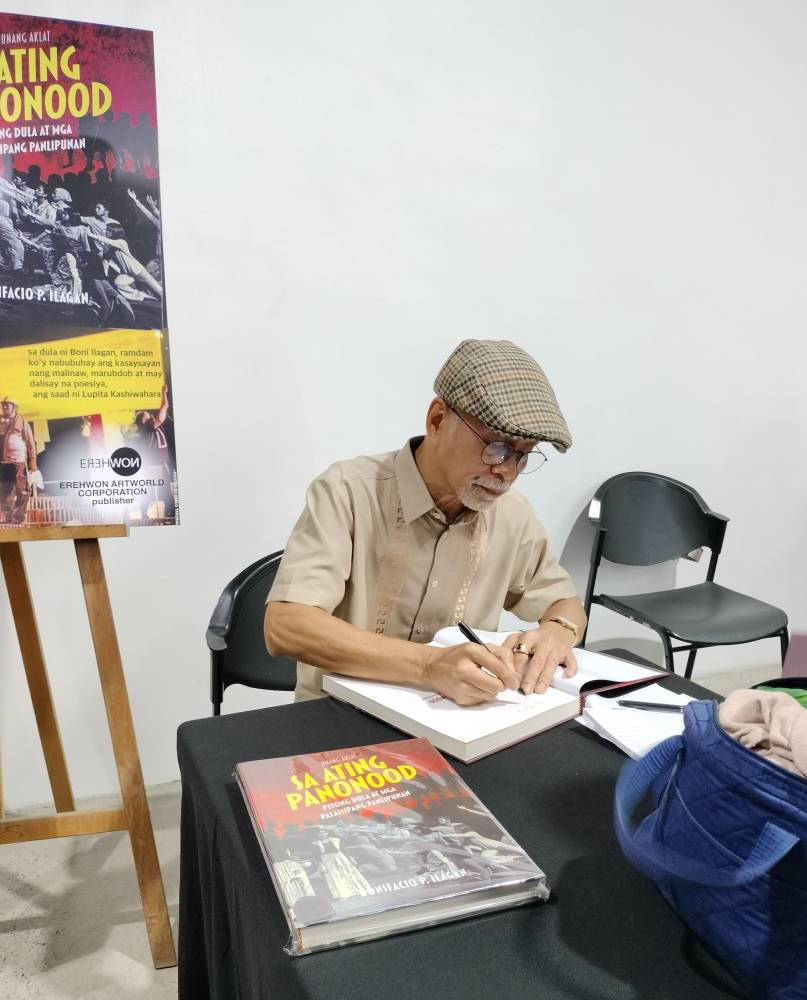

Tell the story

Director JL Burgos spoke at the launch of Ilagan’s book, “Sa Ating Panonood: Pitong Dula at Mga Palaisipang Panlipunan,” in January at the Gimenez Theater, and his words come to mind. Speaking in Filipino, Burgos said Ilagan told him to never pass up the chance to explain what’s happening to the country.

Ilagan himself has always walked the talk, constantly telling people of what has happened and is still happening in this country.

He acquaints Gen Z et al. through “O, Pag-ibig” of the Philippines’ colonial history, the present with its eerie feeling of déjà vu, the insidious culture of impunity and trolling, and the importance of critical thinking. The play’s subject matter is evidently serious, yet Ilagan and associate director Brian Arda’s narration strikes a balance between gravitas and levity.

Ilagan’s voice is heard through Remegia, cute and ebullient, who conveys his contention that critical thinking will prevent injustice, fanaticism, and obscurantism. The actress Sanoy uses the Brechtian technique of addressing the audience, and she holds that audience to rapt attention whether she is singing, narrating, or delivering a soliloquy.

Ilagan and Arda effectively narrate the romance of Oryang and Andres in the tradition of the K-drama rom-com series, effectively connecting with the audience. There’s the trope of an awkward display of affection in the hair’s breadth proximity of the lovers in their secret rendezvous. There’s the age-gap trope, but in reverse—the noona (older woman) romance becomes an oppa (older man) romance. When they fall in love, Andres is pushing 30 and Oryang is 17 (18 according to Agoncillo).

The third trope is the arranged marriage—Oryang’s parents want to arrange her marriage to a man deemed more suitable than Andres. Lastly, the abusive-parents trope has Oryang separated from her Andres, whisked off to literally be imprisoned in a room at her godparents’ house, with the door locked and windows nailed shut.

Mindful, not mindless

Activists/revolutionaries are often cast as villains in this era of disinformation and red-tagging, and much of local entertainment has rendered many Filipinos unquestioning and uncritical. It is against this atmosphere that “O, Pag-ibig” breaks the “norm” by elevating discussions on such issues as authoritarianism, impunity, and the faltering educational system.

Ilagan endeavors to make his audience mindful of what is going on in the country and the pressing need for long-term solutions, not temporary fixes, to pressing problems.

He also settles the faulty concept of love as nonpolitical. Using Oryang and Andres as examples, he asserts that love is political; love calls out all forms of discrimination (racial, social, gender); love rectifies grievances. Love faces challenges and springs into action when needed. Love is concern, love is empathy, for people.

“O, Pag-ibig” is Ilagan narrating the state of the Philippines and insisting that Filipinos can be like Oryang and Andres because, as the Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara said, “the true revolutionary is guided by a great feeling of love.”

“O, Pag-ibig na Makapangyarihan” goes on stage again at the Ignacio B. Gimenez Theater in University of the Philippines Diliman on March 7 at 7 p.m. and March 8 and 9 at 2:30 p.m. and 7 p.m. Tickets are at P800 and at P500 for senior citizens, PWDs, and students. Contact Xian Guevarra at +63 9023 872 3634.