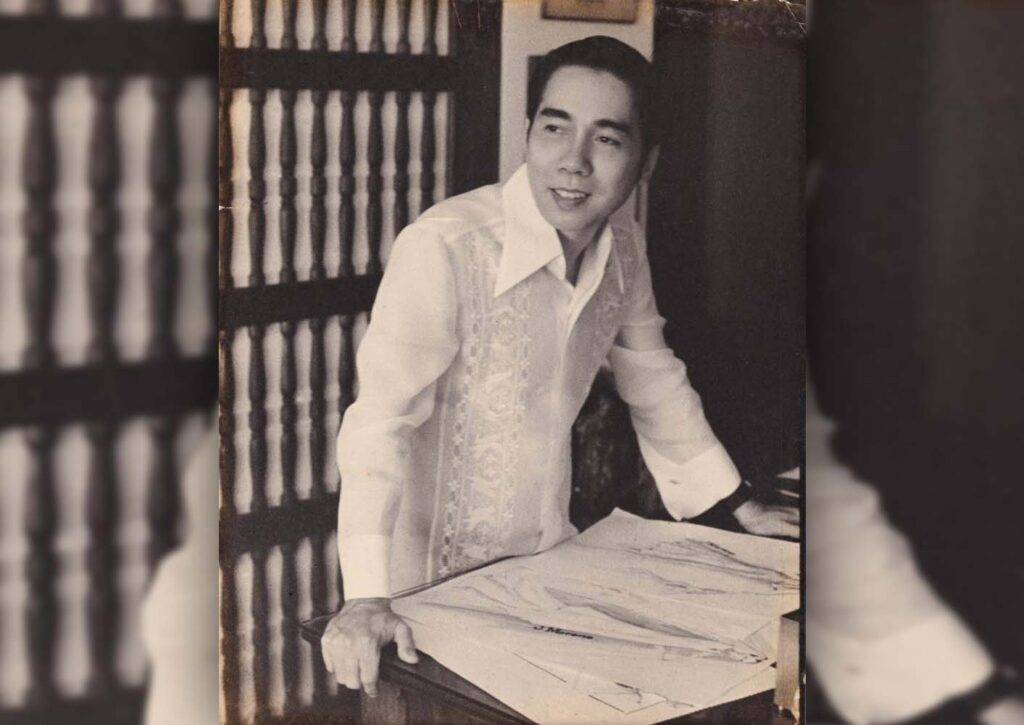

Decoding Pitoy Moreno in centenary exhibit

The “Timeless: J. Moreno” exhibition opens with a striking display: velvet ternos with bubble peplums, adorned with shells and floral embroidery. Sections of the Metropolitan Museum of Manila gallery are dedicated to first ladies’ ternos, formals from Jose “Pitoy” Moreno’s (1930-2018) touring shows highlighting embroidery, beadwork, or the phoenix motif, and Bayanihan dance costumes that give way to the socialites’ wedding gowns.

Maricris Floirendo-Brias’ wedding gown, made in 1986, has puff sleeves, reminiscent of Princess Diana’s. Instead of referencing the creation by David and Elizabeth Emanuel, Moreno crafted it from delicate piña, the paneled skirt a graceful nod to the Maria Clara. This melding is what Fil-Am fashion curator Clarissa Esguerra, a consultant for the exhibit, highlighted in an interview with Lifestyle.

“I look at his clothes through the lens of Western fashion history, understanding its impact on the Maria Clara, and later, designers like Pitoy,” she explained.

Moreno’s creativity, she said, lay in his ability to craft garments that empowered women on a global stage, seamlessly weaving Philippine textiles and motifs into Western silhouettes, a powerful, silent language of cultural fusion.

“Timeless: J. Moreno,” a landmark exhibit and book, commemorates the designer’s centenary. Lead curator and book editor Nina Capistrano-Baker assembled a team of experts, including museologist Ditas Samson, textile expert Sandra Castro-Baker, and Esguerra to analyze Moreno’s aesthetics, cultural influences, and impact. The book is an indispensable chronicle of how he became the most influential designer in the Philippines and the Fashion Czar of Asia. The book and exhibit explore how he successfully bridged the gap between Western fashion and the rich heritage of Philippine textiles and crafts.

Fashion as art

Esguerra, costume and textiles curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma), was responsible for mounting Moreno’s clothing using specialized techniques to ensure proper fit on mannequins for both the book’s photographs and the exhibit. She also contributed an essay placing Moreno’s designs within the context of 20th-century Western fashion.

“These displays aim to show fashion as art, helping people understand that designers often share a similar creative process with fine artists, even though they may use different mediums like painting, sculpture, prints, or photography,” she said.

The curator further explained, “Pitoy was very good at creating looks for women who desired to make an entrance, to make a statement. His clientele included very powerful women, and he understood that clothes were a form of communication, a nonverbal form. When you see a woman wearing one of his dresses in, for example, an international context with diplomats and other high-ranking people from many different countries, she is wearing something that is Western in cut, but made with the textiles of the Philippines. This allowed her to express Philippine identity and be recognized as such, while remaining relatable to a Western audience. The exhibit demonstrates that Pitoy mastered the Western dress, enabling this global representation.”

While acknowledging Moreno’s nationalism, Esguerra also recognized influences from prominent Western designers such as Valentino Garavani, Christian Dior, and Cristobal Balenciaga. “He followed fashion trends but always from the Filipino viewpoint,” she noted.

For instance, the ternos with bubble peplums from his 1990s fashion shows echoed Pierre Cardin’s exploration of rounded, tucked-under hems in the 1950s. The evolution of the bubble skirt, as seen in Balenciaga and Dior, further illustrates this cross-pollination of ideas.

“Even in European fashion circles, designers copied each other,” Esguerra explained. “Oftentimes, clients want to express fashionability. And that might mean wearing a similar silhouette that they’ve seen from another designer.”

She pointed to Dior’s influence, particularly the New Look with its nipped waist and voluminous skirt, visible in Moreno’s pink Filipiniana with piña and callado embroidery. Similarly, a terno done in sequined leopard print recalled Yves Saint Laurent’s recurring motif from the 1980s. This animal print was also explored by Azzedine Alaïa and James Galanos.

Visually interesting

The exhibit further highlighted Moreno’s collaboration with the Bayanihan Dance Company, working closely with costume director Isabel Santos. The black-and-white maria claras inspired his own black-and-white collection for his traveling fashion shows. His signature Maranao princess costume for singkil, widely imitated by other dance companies, exemplified his cultural sensitivity.

“He purposefully referenced the culture of Southern Philippines,” Esguerra said. “With a wrap skirt and a tight blouse, the woman has to be able to dance in it. Also, there’s tons of beads and sequins so that she really sparkled on stage. There’s a lot of visual interest on her. I liked it because he’s being sensitive to the dress of that region. That was the same with dances from the lowland Christian groups where they have the big skirts and the maria clara ensembles, he’s referencing that fashion history.”

Charlene Gonzalez’s gold blouse and red pantsuit, featuring T’boli, Bagobo, and Higanon inspirations, along with a feathered and pearled fan-shaped headdress, won Best National Costume at the Miss Universe 1994 pageant.

Esguerra said, “I saw the Ayala exhibition on Philippine indigenous dress. It was interesting to see his referencing the ikat-dyed abaca, beaded belts, and cast iron bells. It was showy, as she was Miss Universe (Philippines), with a bold headdress. Importantly, he avoided the maria clara or terno, opting for a costume from a different Philippine region, showcasing the country’s diverse cultures.”

Working on “Timeless: J. Moreno” proved a rewarding experience for Esguerra, who, born and raised in the United States, found it a reconnection with her Filipino roots. “It has been a great experience to be exposed to the immense creativity of Filipino fashion designers,” she said.

During her trip, Esguerra discovered Philippine textiles and their modern applications, potential resource materials for the Lacma as it diversifies its collection to better represent various communities.

“People think fashion is a Western concept, and it is not. The West does not have control of fashion. Fashion is anything that changes over time,” she maintained.

Ultimately, she hopes that young designers and students will appreciate the rich history of modern Philippine fashion. “They just shouldn’t look at Balenciaga and other internationally famous ones. They should learn from the Filipino designers who paved the way for them,” Esguerra said.