‘Palayok’ takes center stage in Bicol museum

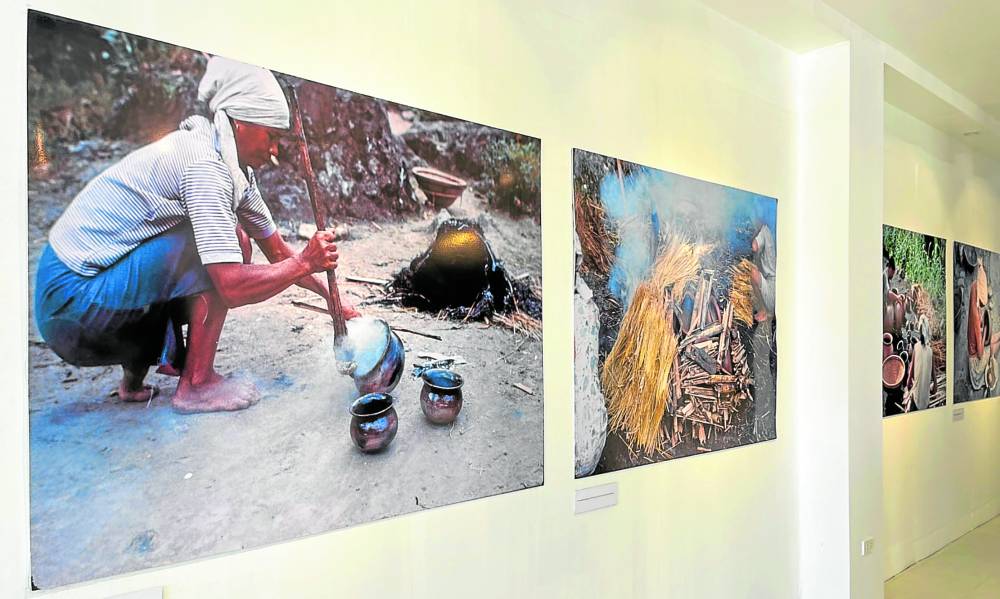

The lowly but anthropologically and archaeologically significant palayok or earthenware pots are featured in an ongoing exhibition at Museo de Isarog (MDI) of the Partido State University (ParSU) in Goa, Camarines Sur.

The exhibit, “Longacre’s Legacy: Ethnoarchaeology and Studies on Philippine Earthenware,” highlights pots collected by American archaeologist Dr. William “Bill” Longacre (1937-2015) in the provinces of Kalinga and Sorsogon.

Longacre, a Michigan native and longtime educator at the University of Arizona, was a trailblazer in what is called processual archaeology, a multifaceted theoretical and methodological branch of anthropological archaeology that studies the surviving material culture of the past to fully understand the dynamics and culture of a group or groups.

Essential tools

In the exhibit, Longacre is noted to have “transformed the field of archaeology by strengthening ethnoarchaeology and pottery studies as essential tools for understanding human cultures over time.”

Ethnoarchaeology is a study of contemporary cultural materials and activities to understand and give context to archaeological materials and anthropological sites.

Longacre is known for his ethnoarchaeological studies in the country, notably the “Kalinga Ethnoarchaeological Project” in the 1970s and 1980s which explored the profound connections between the lifeways of the community vis-a-vis the everyday objects they are using.

The exhibit of Longacre’s collection is a collaboration between the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Southeast Asian Archaeology Lab at UCLA, and the MDI-ParSU.

It is part of the four-day “Workshop: Collaborative and Integrative Climate Research in Southeast Asia” held in ParSU and the Villa Caceres Hotel in Naga City.

Part of a larger collection, 10 ethnographic cooking pots—two from Paradijon in Gubat, Sorsogon, and eight from Kalinga—are on exhibit.

Collected by Longacre during his research in the country from 1970s to 2010s, these pots were donated to ParSU following his death in 2015.

Archaeologist and Camarines Sur native Stephen Acabado of the UCLA said the exhibit “aims to break the regional silos that characterize the state university systems” and with this, ParSU is “advancing scholarship beyond Bicol.”

These pots, said Acabado, “revolutionized the way archaeologists interpret pottery by demonstrating how ceramics reflect social behavior, economic interpretations, and kinship networks.”

Detailed observations

Longacre’s Kalinga project is significant in the field of ethnoarchaeology as it “provided some of the most detailed observations of ceramic production and distribution ever recorded,” giving a link between the ancient and contemporary communal setup.

Through his Kalinga study, Longacre brought to fore the vigorous trade system, community relationships, and shifting social structures in the cultures he studied.

“His findings challenged traditional archaeological assumptions and provided a more nuanced way to interpret ceramics in excavations worldwide,” showing “that pottery style and form were shaped by social connections rather than rigid ethnic identities,” said Acabado.

Bicol’s pottery tradition, which differs from that of Kalinga, provides insights into lowland pottery production, trade, and usage.

Acabado said Longacre’s pioneering work “remains a cornerstone of ethnoarchaeology, linking material culture with the lived experiences of the people who made and used it.”

During the exhibit opening, Miriam Stark, Longacre’s former student and colleague, described the latter as an accomplished scholar who was part of a group of “new archaeologists” who challenged traditional archaeological tenets.

Like other ethnoarchaeologists, Longacre “contended that contemporary ethnographic research, designed with archaeological questions in mind, offered the interpretive potential for strengthening archaeological inference.”

“We looked to him to show us proper conduct, from how to traverse the local bridges, how to sing in public, how to dance the traditional courtship dance, and also how to make friends with the Kalinga hosts and neighbors in the villages where we did our work,” Stark said.

Longacre was so well loved in Kalinga, she recalled, that a baby boy in 1975 was even named after him.