Individual voices in 3 artistic Filipino families

It runs in the family …” goes the familiar expression. It means a trait, quality, or characteristic is shared among family members. In the arts, it can also mean something. Hereditary—a DNA of artistry has been passed down from generation to generation. This family is then said to have formed an artistic dynasty.

Our country, blessed with artistic talents, has produced families bearing the genes of creativity. The rare exhibition at the Reflections Gallery at Museo Orlina selected three paterfamilias: Angelito Antonio, Abdulmari Imao, and Angel Cacnio. Joining them are their descendants, proud progeny, and bearers of their unique artistic genes.

Whether their works are in direct continuity or divergence, what is incontrovertible is the estimable force of dedication and commitment to their direction and journey.

The Antonios

Angelito Antonio is a master of the urban folk genre, popularized by National Artist Vicente Manansala and pursued by Anita Magsaysay-Ho and Malang. Indeed, Manansala mentored Antonio while he was a student at the University of Santo Tomas. In this mainly Filipino idiom, artists depict everyday activities at home and in the marketplace. While these humble settings seem to have no significance or symbolism, they provide a rich tapestry of images and a palette of colors that capture and crystalize the Filipino spirit and way of life.

Despite the commonality of subjects, an individual style of pictorialism distinguishes the works of one urban artist from another. Antonio evolved a fragmentation of forms and planes—an acknowledged debt to Manansala—that is brisk, aggressive, sharp-edged, and abrupt but decisive in delineating the human figure. Like a musician with a perfect pitch, Antonio manifests his draftsmanship in treating human physiognomy as puzzle pieces in a dynamic assemblage of planes and facets. In particular, his black-and-white works are deftly etched masterstrokes.

Antonio’s wife Norma Belleza has her domain in which she reigns, whether in market scenes, kitchen still lifes, street vendors, or the mother-and-child theme. Her compositions are dense with details and ornaments, confirming a persistent horror vacui, a style of art that fills the entire work surface with detail to avoid space. The term is Latin for “fear of emptiness.” Indeed, by her admission, the artist even makes her presence seen by evoking herself in the visages of the tindera and the nanay. Unbeknownst to the public, this has become a sort of signature motif.

Marcel Antonio’s works, too, are in a world of their own, starkly alien to the native folk realm of his parents’ art. He conjures psychologically charged figures in settings that may look domestic but are, in fact, open spaces of the psyche. Whether as single figures or in multiple configurations, the viewer senses they have been cast verily like actors in a mise-en-scene, driving the artist-cum-director’s narrative vision. While they are fully realized human figures, each is emotionally detached and seems to relate to the viewer as abstract constructs. But so powerful is the tension of the narrative pull that we are nonetheless drawn to their distant gaze and remarkable presence.

Fatima Antonio Baquiran’s floral bouquet fills the viewer’s eyes with a surfeit of brilliant colors of her crowded petals, all massed into the plumply delicate Chinoiserie vase, itself circled with ornamental minuscule florals. Like music’s handful of notes, inexhaustible in its variation and permutations, floral painting, with nature’s invariable botanical species, is capable of endless efflorescence.

The Imaos

Sculptural art was once reserved for solemn, monumental, ambitious, noble, and heroic themes. Today, the sculptural imagination, stirred and whipped up by the spirit of whimsy, buoyancy, charm, and the carnivalesque, unleashes the playful aesthetics of childhood and innocence. Indeed, sculptors today are in the throes of three-dimensional revelry as they celebrate childhood games and merriment.

Abdulmari Asia Imao was the first Bangsamoro National Artist. His art, both in painting and sculpture, is dominated by the single most potent icon of the Muslim world: the sarimanok. It comes from the word “sari,” a garment of different colors, and “manok,” a rooster of colorful feathers. The sarimanok signifies good fortune and prosperity. It is the essential trademark of their art forms.

His father nicknamed Toym Imao after his first national award as a young man: Ten Outstanding Young Men of the Philippines, more popularly known as the TOYM Awards. Not surprisingly, Toym turned out to be an achiever himself. His Bachelor of Science in Architecture was earned from the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman in 1999, while his Master of Fine Arts in Sculpture was attained from the Maryland Institute College of Art-Rinehart School of Sculpture in Baltimore, Maryland, in 2012.

Toym produced a talented progeny of sculptors, son Diego and daughter Kahlo. Diego works in various mediums, such as video and graphic design, and conceptualizes sculptural installations for multiple spaces. On the other hand, Kahlo plunges deep into the deep blue waters of her pictorial space, and like the sharks that inhabit it, her imagination never remains still.

For this family of sculptors, a subject like kite-flying is more than just an ode to childhood’s summer. Admiring a vibrant, multicolored construction of a profusion of ribbon-like sheets of little kites forming a tail trailing a mother kite, the viewer imagines their free-spirited flight up in the skies. In their vivacious imagination, sculptures may emerge uncannily from the least expected stimuli, taking them as exhilarating points of departure.

The Cacnios

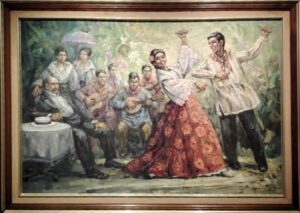

Angel Cacnio, a peer of the UP-bred artists like Jose Joya, Juvenal Sanso, and Rodolfo Ragodon, painted historical scenes, festive occasions, and classic Philippine images like cockfighting, market vendors, dancers in colorful native garb, harvest scenes, serenaders, families saying grace before meals, the mother and child, and other scenes from his hometown Malabon. Indeed, it is admirable that Filipino artists use their hometowns and provinces as emotional impetus for their creative visions. A childhood immersed in the memories of Malabon provided Canio with a rich tradition that sustained him for a lifetime.

Living under the shadow of distinguished parentage can be either a blessing or a burden. Michael Cacnio found himself at such a crossroads. This crucial issue led him to choose the three-dimensional art of sculpture. But while his chosen idiom departed from his father’s, the font of inspiration—his childhood memories of games growing up in Malabon—remained vivid and alive.

Working in brass and other metals, Michael distinguished himself with his chosen subjects: balloons, kites, and other Filipino games. His simple themes were so influential that they spawned a slew of imitators. The works are enhanced by highly refined craftsmanship, and the incorporation of intensely chromatic colors charges the works with a frisky dynamism.

Opting to be known by a single moniker, Teo, like his father Michael, was similarly determined to find his own identity. Impressively, at a very young age, observing his father at work opened up the wonders of sculpture to him. Teo’s works are an adventurous amalgamation of painting and sculpture, while his gleaming freestanding works in aluminum, inflected with fun-house surreal distortions, already show a sculptural imagination unfettered by reason and logic.

The Antonio, Imao, and Cacnio families teach us that genuine artistry’s momentum is self-propelled and motivated through the succession of generations. Individuality is what is to be nourished, nurtured, and treasured. As an unknown wise man has sagely observed: “Families are like branches in a tree; we grow in different directions, yet our roots remain as one.”

“Artistic Legacies” runs until March 31.