‘Pilato’: Thank heavens for the heavenly music

Over 2,000 years ago, a Roman prefect named Pontius Pilate became the reluctant catalyst for the trial, torture, and crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Fast-forward to the present, and “Pilato,” an original sung-through Filipino musical, dared to give voice and the spotlight to this infamous figure—a man often cast as a footnote to the world’s greatest martyrdom.

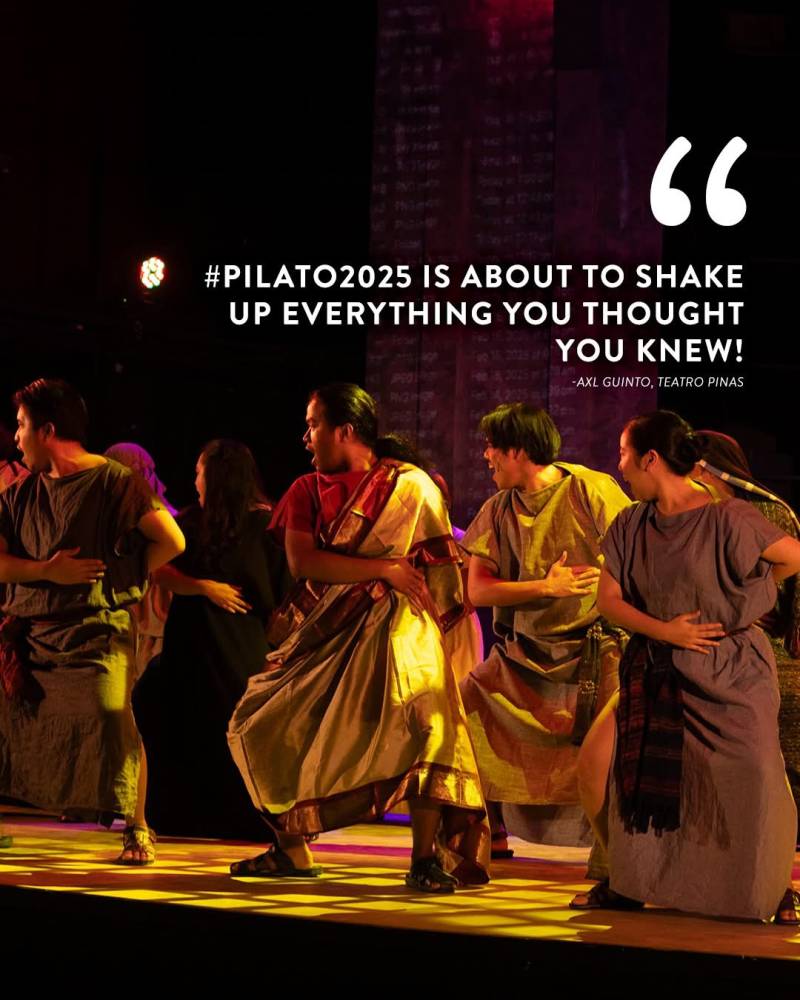

Premiering at the PETA Theater Center during the penultimate week of Lent, running until April 13, “Pilato” was the inaugural production by The Corner Studio. And while its ambition was admirable, its execution revealed both promise and pitfalls.

A production like “Pilato” must overcome two things to earn its place on the stage: first, to build a compelling portrait of Pilate—not just as a one-dimensional villain, but as a man caught between conscience and empire, racked with doubt and consequence. Second, it must reframe the familiar through the unfamiliar—to trace the origin of the antagonist, not to absolve him, but to understand his character.

It’s a time-honored theatrical tradition. From Stephen Schwartz’s “Wicked” (2003), which redeemed the Wicked Witch of the West, and Stephen Sondheim’s “Sweeney Todd” (1979), which explored how injustice begets monstrosity, to Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “Jesus Christ Superstar” (1970), which cast Judas as a tragic, disillusioned figure, musicals have long looked into the soul of the so-called damned.

“Pilato” bids fair to join this lineage. But the show we saw never quite found its footing. What should have felt like a moral crucible ended up as a series of moments that skimmed the surface without ever plunging into the deep.

Much of this is due to a central performance that failed to command the narrative.

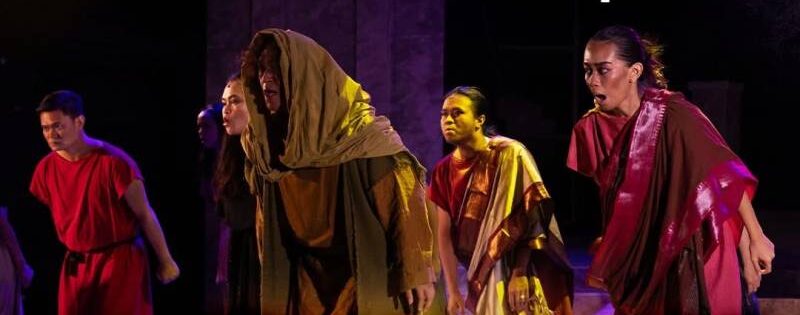

Jerome Ferguson’s Pilato was frustratingly one-note. His vocal performance was serviceable but emotionally vacant. From his wife Procla’s laments about their marriage—compounded by his alcoholism and the trauma of a miscarriage—and the impending unrest among the Judean crowds, to the political tightrope he walked in trying to appease both the mob and the Roman empire, Ferguson’s expression barely flickered. His Pilate was stone-faced even when the story cried out for doubt, for anguish, for humanity. When his breakdown finally arrived near the end of Act II, it felt abrupt, dramatically unearned, and jarringly out of character.

Upstaged

Whether it was a failure of direction (by Eldrin Veloso), performance, or the writing itself (also by Veloso), what became certain was this: Pilato was consistently upstaged by the supporting cast, whose vitality made the title character’s flatness all the more glaring.

Christy Lagapa, as Procla—canonically an underdeveloped character relegated in the Bible to a single foreboding dream—infused the role with clarity and emotional precision. Her vocals were both ethereal and urgent. Please give her more roles. Onyl Torres’ Josefo, likely inspired by the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, served as both scribe and conscience—an external narrator drifting in and out of scenes with curious timing, but providing textured commentary. He was Pilato’s whisperer of self-awareness, offering the nuance the main character rarely provided.

The trio of Publius, Decimus, and Marcus—not soldiers in the strict sense but more like Pilate’s courtly advisors or bureaucratic confidants—supplied much-needed comic levity. Their interjections often broke the somber tension, though they sometimes pulled the tone into sitcom territory. Still, they were a welcome release valve in a musical otherwise drenched in angst.

And then there was Jeremy Manite’s Caiaphas—a tenor of remarkable precision whose performance blended vocal brilliance with a slick political cunning befitting the high priest who would engineer Christ’s fate. His presence sharpened every scene he entered.

These characters, vivid and dimensional, formed a chorus of compelling subplots. And that was the problem. In a show titled “Pilato,” the gravitational pull was everywhere but in the center.

The music, by contrast, was heavenly. Pauline Arejola’s musical direction and Yanni Robeniol’s compositions conjured a sonic world that was rich, reverent, and emotionally generous. The ensemble delivered with full-bodied resonance—uniformly strong, often transcendent. Close your eyes, and you were lifted. The harmonies swelled like a procession of angels. It was the kind of music that wrapped around your chest and momentarily convinced you that everything would be okay.

Inert, uninspired

But open your eyes—and there was trouble.

Tsard Chua’s set design was uninspired, bordering on inert. The choreography was often stiff and awkward, especially during large ensemble scenes, where the Judeans moved more like marionettes than motivated characters. The costumes—a mishmash of vaguely Roman tunics and clunky silhouettes—lacked any unifying visual language, feeling more like a crowded village from different ends of the globe than the polished pageantry of a historical drama. Not any better were the static, unimaginative projections meant to contextualize the setting. Rather than elevating the visual landscape, they distracted from and dulled it.

Unfortunately for “Pilato,” musicals are made not just for the ears, but also for the eyes. And while the music achieved rapture, the visuals were crying out for resurrection.

We already knew the facts: Pilate saw no legal reason to execute Jesus but feared public unrest. He used the custom of releasing a prisoner at Passover to shift accountability. He washed his hands of the matter—literally. But what the musical didn’t fully explore was the man beneath the myth. What was Pilate’s upbringing? What ghosts haunted him in the night? Was there a moment, perhaps earlier in life, when he vowed never to be seen as weak? Did he truly believe Jesus was innocent—or was that just a performance for posterity?

These were the questions “Pilato” hinted at but never truly wrestled with. Instead, we’re told that “what is written is written”—a fatalistic shrug rather than a dramatic excavation. “Pilato” presented the dilemma, but refused to dig. It gestured toward empathy, but eventually played it much too safe.

“Pilato” ran April 4-13 at Peta Theater Center.