Abstract dance challenges Filipino taste

Importing a famous work by a knighted choreographer was no mean feat for Christopher Mohnani, the Arts and Culture manager of Circuit Makati. Wayne McGregor CBE’s “Autobiography” opened the second International Dance Festival (IDF) at the Samsung Theater to a supportive dance community. It’s about time, as the local dance scene has lagged in showcasing works by the world’s best choreographers, and has grown too comfortable with redundant classical and neoclassical choreography. Even contemporary dance here often lacks innovation and maturity.

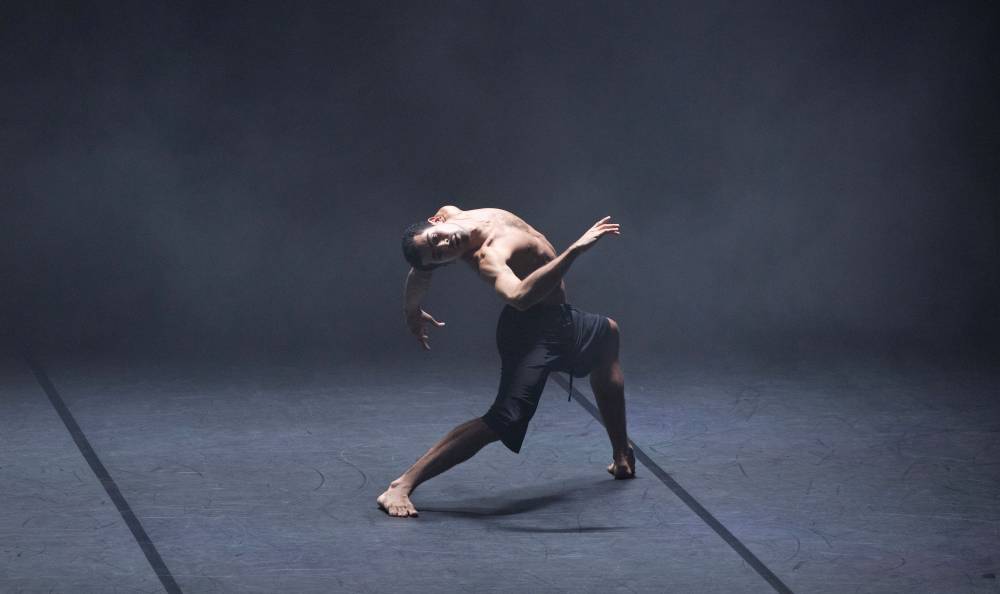

McGregor is known for his experimental style performed by dancers possessing Olympic-level strength, and his choreography’s interface with avant-garde music and technology. It’s a treat for us to be educated by witnessing dance of this caliber. Associate artistic director Odette Hughes aptly said, “Wayne is a physical genius, a creative genius, and quite funny. He’s also kind, incredibly intellectual, and simply brings a wealth of amazing gifts to the table.”

However, McGregor’s choreography isn’t for everyone. Unless you grasp the British choreographer’s cerebral approach and his collaborative working style, appreciating “Autobiography” might prove challenging.

The theme itself is unusual: “Autobiography” comprises 23 sections, each reflecting a pair of chromosomes in the human genome based on McGregor’s DNA. Artificial intelligence, through a computer-generated algorithm, determines the show’s sequence. Consequently, the order of the dances varies with each performance. The algorithm has 23 sections to choose from and selects 15 for each performance with a running time of 75 minutes. While the algorithm’s specific order is revealed just before the show, the opening and ending dances remain constant.

Freedom to explore

Given the limited production timeline in the IDF, “Autobiography (v.105)” is comprised of 13 dances, with a 70-minute running time, a bare set but scaled-down yet atmospherically stunning lighting design by Lucy Carter.

Dancer Rebecca Bassett-Graham mused, “Isn’t that the beauty of it? We never reveal what to feel or the order of events. It’s for each individual in the audience to find something that resonates with their experiences. Similarly, during creation, Wayne never told us, ‘This piece is about X.’ We always had the freedom to explore an idea, feeling, or event from our own lives. So, I feel like everyone almost has their own story, and every performance is different, just like every day changes.”

“Autobiography (v.105)” mirrored a DNA animation, its dances structured to echo the body’s precise blueprint. McGregor imbued each segment with a cryptic theme, inviting audience interpretation. The performance opened with “Avatar,” a solo depicting a loose-jointed male starting his life’s journey.

One section drew inspiration from McGregor’s birth date, March 12, 1970.

“We actually used those numbers as a way of tasking,” said Basset-Graham. “It has a specific feel, like electrical current and energy, derived from those numbers. He sets a movement task, and it’s up to us to interpret it. We created movement within a structure based on one, two, zero, three—his birth date. Very abstractly, you, the audience, wouldn’t know.”

“World” presented a brooding and intriguing dynamic between two men, contrasted by a separate group’s pensive, slow movements bathed in a warm glow. The performance continued with a tense duet between a man and a woman, marked by sharp, intense movements, and a subsequent dance of two men whose careful interactions hinted at ambiguous feelings. The ending saw the group leaving Bassett-Graham alone on stage.

“The end is like a goodbye,” she said. “Whether that’s a goodbye to life as we know it or goodbye to those whom you love. But it is also a freedom and willingness to step into what is next. What is the afterlife? Is there one? Be ready for it.”

Asked how it felt to perform a difference sequence each time, Bassett-Graham, one of the pioneering dancers of this piece, explained, “Having done it over and over, even 105 versions later,

‘Autobiography’ retains a sense of newness and a real human quality. As dancers, the specific order of movements doesn’t matter as much as the transitions between them and the human interaction within those transitions. In one show, I might not see someone for a long time, and then suddenly they’re walking towards me to dance or just pass by to dance with someone else. It has this truly human element.”

Androgynous visual landscape

In his maverick approach, as seen in “Autobiography,” McGregor presented an androgynous visual landscape. Women, clad in flesh-colored leotards over loose bottoms, moved with a masculine dynamism, even carrying bodies. Notably, in many shows, critics were impressed by two transgender dancers who exhibited both grace and Herculean strength, while the male dancers moved with tenderness. The choreography featured a blend of floor-based movements—sliding and gliding—alongside classical ballet vocabulary, including multiple pirouettes in attitude (bent leg at 90 degrees), pas de chat (catlike jump), and brisé dessus-dessous (beaten leg to the front and back), punctuated by rippling torsos, body isolations, suspended leaps, speedy moves, and intricate contortions.

Bassett-Graham reflected, “It’s pushed me physically to reach new heights, constantly testing and breaking my limits, then setting new ones. Creatively and mentally, it’s challenged how I think when approaching a creation or moving my body, constantly questioning the why and how to discover newness. It’s pushed me to trust my instincts and not doubt them.”

Recalling her dancing days with McGregor, Hughes exclaimed, “I found it super exciting! It made me dance in ways I never thought possible. I didn’t even realize I could get my legs up that high, how far off-balance I could be, or how high I could jump. It’s just electrifying, innovative choreography. I was never bored doing his work; it’s very beautiful.”

She continued, “More importantly, Wayne challenges you creatively. It’s not just about the physicality. It’s about how you think about the work, the tasks you’re given, and how he delivers all this information that your mind then has to process before it becomes a physical act.”

“Autobiography” presented beautiful moments like revelations of truths. Yet, considering the Filipino preference for lighter entertainment over deep philosophical thought, and set against Jlin’s percussive electronic score (including a classical interlude by Italian composer Arcangelo Corelli), the dances likely felt too long, leading to audience “inattention.”

Still, the impact of Company Wayne McGregor remained undeniable. Their genuine interaction as individuals, sharing a real-time experience, lent their performance a powerful and profound meaning. They transcended the role of fellow dancers, connecting as “real people up there.” Reflecting on the ensemble, Bassett-Graham noted, “It’s an incredible group of diverse personalities and movers, each unique. Yet, there’s this almost tangible unity. Sharing so much of life—seeing the world, traveling, the good times, and the hardships—has attuned us to each other even onstage.”