Changing of the guard: BARMM women find empowerment

(First of a series)

Datu Hoffer Ampatuan, Maguindanao del Sur—Samarudin Guimalil Mentong knew that peace, not war, was the key to a better life.

At 20 years old, he had taken over as commander of Camp Omar in the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) war against the government.

But as a peace agreement took hold, Samarudin, a high school graduate, welcomed development initiatives by aid workers in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (BARMM).

He was elected president of the people’s organization (PO) in his barangay two years ago under a novel, bottom-up community-driven program. Here, the people chose from proposals of livelihood projects by donors and aid groups during consultation meetings.

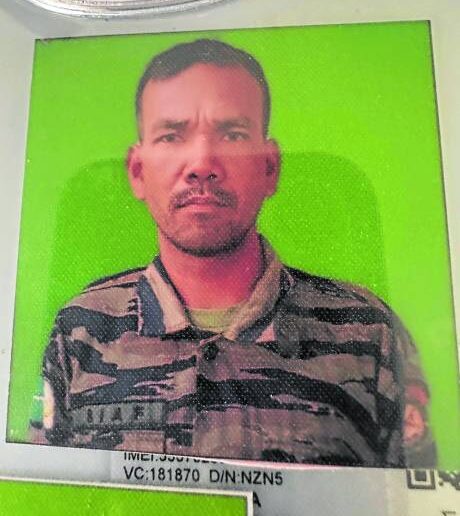

A strapping 35-year-old with Arab looks and a military bearing, Samarudin had just attended a three-hour meeting last September and had hitched a ride to the highway on his way home when gunmen struck, killing him and his two aides.

The MILF commander had survived two previous attacks in his corn farm, said his wife, Muslima, 34. She said her husband had told her the night before that should anything happen to him, she should continue what he had begun.

“You should go on, even if you do it with a heavy heart,” said Muslima, then vice president of the 28-member PO, her eyes misty. “That is what the people want.”

Muslima has taken over as PO president, pursuing activities her husband had started. These include producing coconut oil in the mainly coconut farmland, baking pastries, carpentry.

She supports her three talented daughters by selling sweet potatoes and bananas.

Muslima dismissed news reports that her husband’s death was a result of “rido”—an often bloody squabble over land ownership.

Spanish support

She said his enemies thought he had amassed power and was gaining financially from the Communities for Learning and Employment Project program funded by the Madrid-based Cooperación Española.

Implemented by the international humanitarian agency Community and Family Services International (CFSI), the program provides technical experts, basic tools and implements.

“My father is gone,” Mentong’s daughter Anjap, 14, said in a message on Messenger to Sittie Airah Usman Pendi, 25, a CFSI community organizer.

“I was super affected,” said Airah, “The program really gave hope. It allowed the people to show that survival did not mean dependence on alms alone.”

Children’s playgrounds

Camp Omar is one of six major MILF camps targeted for rehabilitation under a March 2014 peace agreement with the Philippine government.

Following then President Joseph Estrada’s “all-out war” against the MILF, CFSI began “psychosocial” activities for children in evacuation camps, gaining acceptance of local governments initially apprehensive of threats to their authority, the combatants, bandits, kidnappers and other lawless elements.

Dialogues at the grassroots turned into community-driven programs, said Noraida Abdullah Karim, CFSI’s director for Mindanao.

“We became a platform for reconciliation,” said Noraida, because of the agency’s perceived neutrality.

But it also led to close calls. She had seen the wrong end of an Armalite, but has continued to soldier on.

The parties then requested the World Bank to raise $38 million from international donors to finance the building of infrastructure, shelters, health and education facilities in the largely agricultural and forested region reduced to ashes during the MILF wars.

Some 638,000 people—52 percent women—gained from the activities. Where there once was despair, optimism emerged. Hope springs eternal.

It is election season and the excitement is palpable. The armed forces and police behind armored personnel carriers maintain checkpoints along the highways and are courteous and polite.

“Give peace a chance,” proclaims one Philippine National Police truck.

Motorcades of the dominant United Bangsamoro Justice Party of Al Haj Murad Ebrahim, a former chief minister of the BARMM, roam the cities.

WOW

Highways are festooned with portraits of candidates, most scions of prominent rajahs, including a congressional aspirant with movie-star looks named “Dimple.”

Business is booming. A new mall, KCC, has just opened, adding to the string of Robinson’s shopping centers, and competing with ramshackle eateries offering “pastel”—rice and chicken adobo strips.

The grand mosque built by the Sultan of Brunei looms in the distance.

“We have been transformed from a war zone into an economic zone,” said Iskak Managsa, the municipal agriculturist at Matanog.

Managsa organized WOW—Widows of War—to produce and sell coffee, tea, chili powder. Each member earns as much as P1,000 a month, a fortune, from organic farming using fermented fruit juice as fertilizer.

It is something that Muslima Mangi Mentong hopes to achieve in her village.

(The writer is a former reporter and aid worker who has been assigned to conflict zones in Asia, Africa, the Balkans and the Middle East.)