Pontiff’s Creole roots show complex ties of race, church

NEW ORLEANS—The new Pope’s French-sounding last name, Prevost, intrigued Jari Honora, who began digging in the archives and discovered the Pope had deep roots in the city.

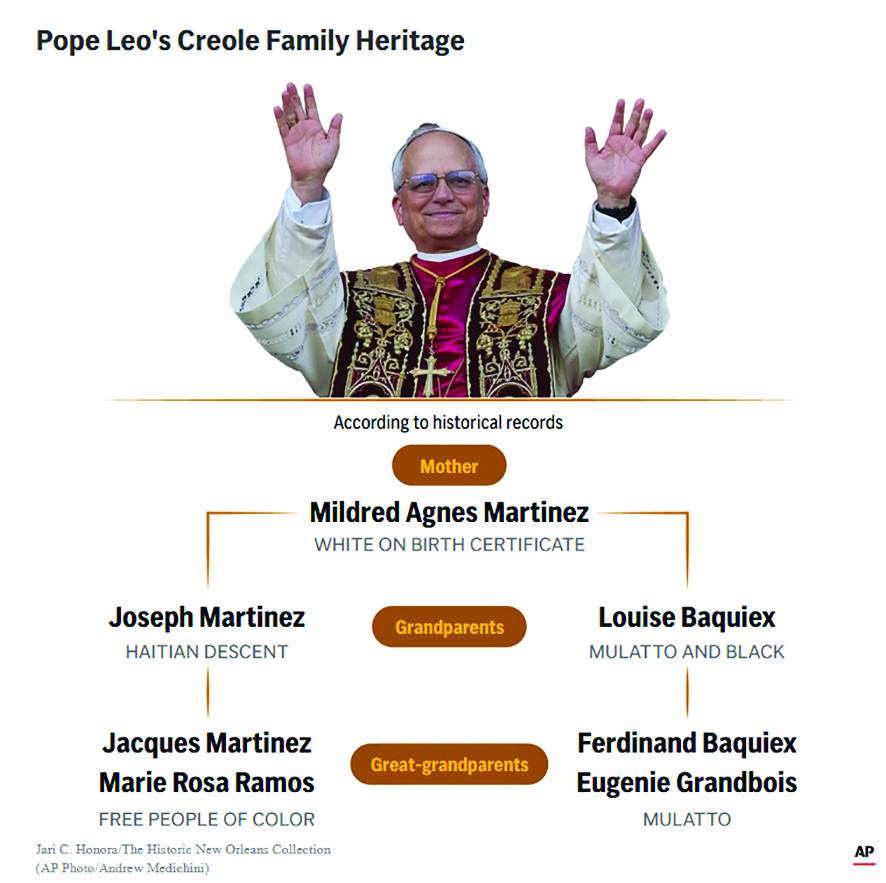

All four of Pope Leo XIV’s maternal great-grandparents were “free people of color” in Louisiana based on 19th-century census records, Honora found.

As part of the melting pot of French, Spanish, African and Native American cultures in the southern state, the Pope’s maternal ancestors would be considered Creole or people of mixed descent.

“It was special for me because I share that heritage and so do many of my friends who are Catholic here in New Orleans,” said Honora, a historian and genealogist at the historic New Orleans Collection, a museum in the French Quarter.

Honora and others in the Black and Creole Catholic communities say the election of Leo—a Chicago native who spent over two decades in Peru—is just what the Catholic Church needs to unify the global church and elevate the profile of Black Catholics, whose history and contributions have long been overlooked.

‘Latino influence’

Leo, who has not spoken openly about his roots, may also have an ancestral connection to Haiti. His grandfather, Joseph Norval Martinez, may have been born there, though historical records are conflicting, Honora said.

But Martinez’s parents—the Pope’s great-grandparents—were living in Louisiana since at least the 1850s, he said.

Andrew Jolivette, a professor of sociology and Afro-Indigenous studies, did his own digging and found the Pope’s ancestry reflected the unique cultural tapestry of southern Louisiana.

“There is Cuban ancestry on his maternal side. So, there are a number of firsts here and it’s a matter of pride for Creoles,” said Jolivette, whose family is Creole from Louisiana.

“So, I also view him as a Latino pope because the influence of Latino heritage cannot be ignored in the conversation about Creoles.”

Most Creoles are Catholic and historically it was their faith that kept families together as they migrated to larger cities like Chicago, Jolivette said.

The former Cardinal Robert Prevost’s maternal grandparents—identified as “mulatto” and “Black” in historical records—were married in New Orleans in 1887 and lived in the city’s historically Creole Seventh Ward.

In the coming years, racial segregation rolled back post-Civil War reforms and “just about every aspect of their lives was circumscribed by race, extending even to the church,” Honora said.

‘Passed for white’

The Pope’s grandparents migrated to Chicago around 1910, like many other African American families leaving the racial oppression of the Deep South, and “passed for white,” Honora said.

The Pope’s mother, Mildred Agnes Martinez, who was born in Chicago, is identified as “white” on her 1912 birth certificate, Honora said.

“You can understand, people may have intentionally sought to obfuscate their heritage,” he said. “Always life has been precarious for people of color in the South, New Orleans included.”

Former New Orleans mayor Marc Morial called the Pope’s family history “an American story of how people escape American racism and American bigotry.”

Morial said the shifting racial identity of the new Pontiff’s maternal family highlights “the idea that in America people had to escape their authenticity to be able to survive.”

The Rev. Ajani Gibson, who heads the predominantly Black congregation at St. Peter Claver Church in New Orleans, said he sees the Pope’s roots as a reaffirmation of African American influence on Catholicism in his city.

“I think a lot of people take for granted that the things that people love most about New Orleans are both Black and Catholic,” said Gibson, referring to rich cultural contributions to Mardi Gras, New Orleans’ jazz tradition and brass band parades known as second-lines.

Kim Harris, associate professor of African American Religious Thought and Practice at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, said the Pope’s genealogy got her thinking about the seven African American Catholics on the path to sainthood who have not yet been canonized.

Harris highlighted Pierre Toussaint, a philanthropist born in Haiti as a slave who became a New York City entrepreneur and was declared “venerable” by Pope John Paul II in 1997.

“The excitement I have in this moment probably has to do with the hope that this Pope’s election will help move this canonization process along,” she said.

Gibson said he hopes the pontiff’s Creole heritage signals an inclusive outlook for the Catholic Church.