On Ireland’s peat bogs, climate action clashes with tradition

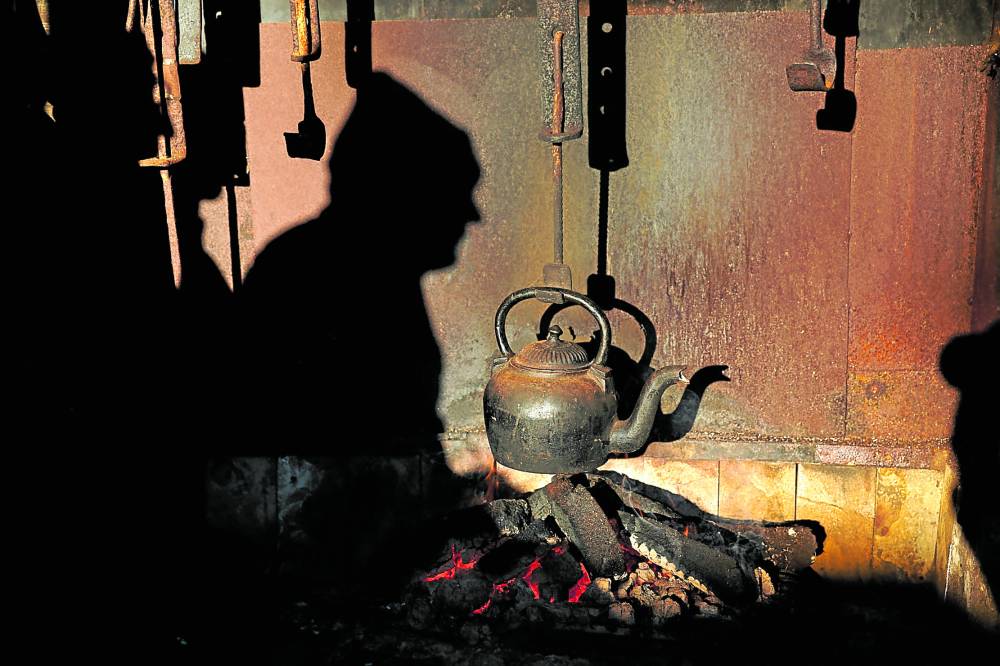

CLONBULLOGUE, IRELAND—As wind turbines on the horizon churn out clean energy, John Smyth bends to stack damp peat—the cheap, smoky fuel he has harvested for half a century.

The painstaking work of “footing turf,” as the process of drying peat for burning is known, is valued by people across rural Ireland as a source of low-cost energy that gives their homes a distinctive smell.

But peat-harvesting has also destroyed precious wildlife habitats, and converted what should be natural stores for carbon dioxide into one of Ireland’s biggest emitters of planet-warming gases.

As the European Union seeks to make Dublin enforce the bloc’s environmental law, peat has become a focus for opposition to policies that Smyth and others criticize as designed by wealthy urbanites with little knowledge of rural reality.

“The people that are coming up with plans to stop people from buying turf or from burning turf… They don’t know what it’s like to live in rural Ireland,” Smyth said. He describes himself as a dinosaur obstructing people that, he says, want to destroy rural Ireland.

“That’s what we are. Dinosaurs. Tormenting them.”

When the peat has dried, Smyth keeps his annual stock in a shed and tosses the sods, one at a time, into a metal stove used for cooking. The stove also heats radiators around his home.

Turf, Smyth says, is for people who cannot afford what he labels “extravagant fuels,” such as gas or electricity. The average Irish household energy bill is almost double, according to Ireland’s utility regulator, the 800 euros ($906) Smyth pays for turf for a year.

Smyth nevertheless acknowledges digging for peat could cease, regardless of politics, as the younger generation has little interest in keeping the tradition alive.

“They don’t want to go to the bog. I don’t blame them,” Smyth said.

Industrial harvesting

Peat has an ancient history.

Over thousands of years, decaying plants in wetland areas formed the bogs.

In drier, lowland parts of Ireland, dome-shaped raised bogs developed as peat accumulated in former glacial lakes. In upland and coastal areas, high rainfall and poor drainage created blanket bogs over large expanses.

In the absence of coal and extensive forests, peat became an important source of fuel.

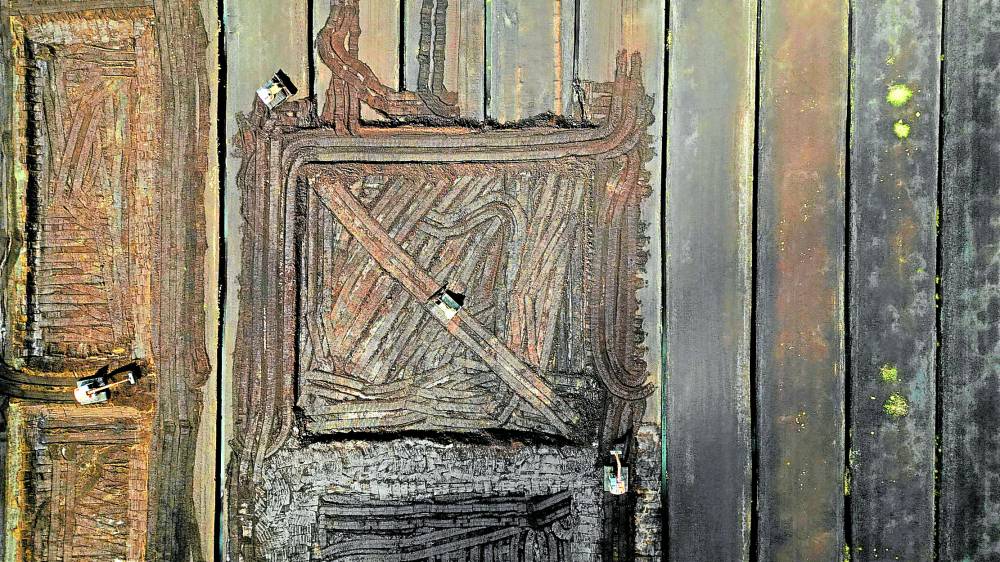

By the second half of the 20th century, hand-cutting and drying had mostly given way to industrial-scale harvesting that reduced many bogs to barren wastelands.

Ireland has lost over 70 percent of its blanket bog and over 80 percent of its raised bogs, according to estimates published by the Irish Peatland Conservation Council and National Parks and Wildlife Service, respectively.

Following pressure from environmentalists, in the 1990s, an EU directive on habitats listed blanket bogs and raised bogs as priority habitats.

As the EU regulation added to the pressure for change, in 2015, semi-state peat harvesting firm Bord na Mona said it planned to end peat extraction and shift to renewable energy.

In 2022, the sale of peat for burning was banned.

An exception was made, however, for “turbary rights,” allowing people to dig turf for their personal use.

Added to that, weak enforcement of complex regulations meant commercial-scale harvesting has continued across the country.

Ireland’s Environmental Protection Agency last year reported 38 large-scale illegal cutting sites, which it reported to local authorities responsible for preventing breaches of the regulation.

The agency also said 350,000 metric tons of peat were exported, mostly for horticulture, in 2023. Data for 2024 has not yet been published.

Green vision

Pippa Hackett, a former Green Party junior minister for agriculture, who runs a farm near to where Smyth lives, said progress was too slow.

“I don’t think it’s likely that we’ll see much action between now and the end of this decade,” Hackett said.

Her party’s efforts to ensure bogs were restored drew aggression from activists in some turf-cutting areas, she said. “They see us as their arch enemy,” she added.

In an election last year, the party lost nine of the 10 seats it had in parliament and was replaced as the third leg of the center-right coalition government by a group of mainly rural independent members of parliament.

The European Commission, which lists over 100 Irish bogs as Special Areas of Conservation, last year referred Ireland to the European Court of Justice for failing to protect them and taking insufficient action to restore the sites.

The country also faces fines of billions of euros if it misses its 2030 carbon reduction target, according to Ireland’s fiscal watchdog and climate groups.

CO2 emissions

Degraded peatlands in Ireland emit 21.6 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent per year, according to a 2022 United Nations report. Ireland’s transport sector, by comparison, emitted 21.4 million tons in 2023, government statistics show.

The Irish government says turf-cutting has ended on almost 80 percent of the raised bog special areas of conservation since 2011.

It has tasked Bord na Mona with “rewetting” the bogs, allowing natural ecosystems to recover, and eventually making the bogs once again carbon sinks. So far, Bord na Mona says it has restored around 20,000 hectares of its 80,000 hectare target.

On many bogs, scientists monitoring emissions have replaced the peat harvesters, while operators of mechanical diggers carve out the most damaged areas to be filled with water.

Bord na Mona is also using the land to generate renewable energy, including wind and solar.

Mark McCorry, ecology manager at Bord na Mona, said eventually the bogs would resume their status as carbon sinks.

“But we have to be realistic that is going to take a long time,” he said.

Reuters, the news and media division of Thomson Reuters, is the world’s largest multimedia news provider, reaching billions of people worldwide every day. Reuters provides business, financial, national and international news to professionals via desktop terminals, the world's media organizations, industry events and directly to consumers.