Aeta folk want more say on Pinatubo tourism boom

BOTOLAN, ZAMBALES—Jordan Mangatoleran, an indigenous Aeta, has faint memories of Mt. Pinatubo’s eruption in 1991, but the sight of the crater lake confirms that fateful event which he witnessed as a 6-year-old.

Now 40, Mangatoleran said that according to his elders, they would notice animals coming down from the mountain months before the eruption — a sign of impending danger.

“We, aetas, listen to animals and nature; they often tell us what to do,” Mangotelaran said in an interview last month.

In April 1991, Aeta families, including Mangatoleran’s, began evacuating from the highlands of Baytan—a cluster of villages comprising Burgos, Nacolcol, Palis, Maguisguis, Cabatuan, Poonbato, Owaog Nebloc and Malomboy to seek refuge in public schools in the town.

After lying dormant for 500 years, Mt. Pinatubo burst back to life on June 15 that year, spewing ash and spreading darkness into the sky in one of the most catastrophic eruptions of the 20th century.

Beautiful disaster

The volcano belched ash into the atmosphere, blanketing vast areas in gray. The pyroclastic flows or lahars that followed engulfed the slopes, filling deep gullies, reshaping the landscape.

The Aeta tribes, who had lived on the slopes for centuries, lost everything—their homes, forests and way of life— as they left the barren, hostile environs behind.

But from the destruction, a thing of beauty—a crater lake—emerged at the Mt. Pinatubo caldera, showing nature’s transformative power.

The lake, which became a popular destination decades after the eruption, is situated within a 15,998-hectare area that was granted to the Aeta communities through a certificate of ancestral domain title (CADT) in 2009. This area covers the villages of Burgos, Villar, Moraza and Belbel in Botolan town, and portions of Cabangan, San Felipe and San Marcelino towns.

Zambales or nearby Tarlac are the typical jump-off points to the lake, which became a popular destination decades after the eruption. The terrain features lahar fields, river crossing, rocky canyons that attract hikers and nature enthusiasts.

Despite the tourism boom in the area, however, some Aeta communities claim they have not received any benefit or seen seen a basic accounting of the revenue generated, which reports place at hundreds of millions of pesos over the last decade.

Compensation issues

In a phone interview on May 19, Aeta leader Chito Balintay said they met with village chiefs together with the National Commission of Indigenous People (NCIP) representatives in 2014 after noting the rising number of tourists. They then formed a Pinatubo Task Force which initially managed the tours.

But in 2016, said Balintay, the Botolan local government unit (LGU) took control of operations.

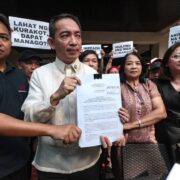

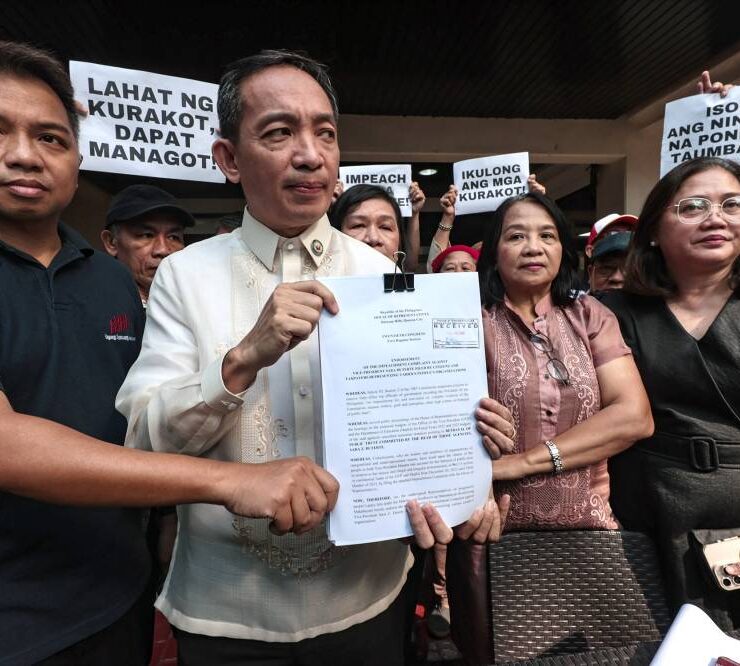

To protest the lack of compensation and failure to recognize their ancestral domain, members of the Aeta communities blocked access to the Mt. Pinatubo crater. Some protesters were detained on April 18 by the police but were released the same day.

The Department of Tourism (DOT) announced on May 4 the suspension of all tourism activities and projects on the mountain, a move that aligned with Executive Order No. 5 issued by the Botolan LGU.

Botolan Mayor Jun Omar Ebdane, however, said the suspension was to make way for the construction of roads that were damaged on May 1 and not due to the issues of compensation.

“It’s not on our part because we have all the receipts, and our tourism officer made sure that communities got their share,” said Ebdane in a phone interview on May 19.

Ebdane recalled that a Pinatubo Commission was created in 2016 by former Mayor Doris Maniquiz so the Indigenous People will share in the responsibility and in the tourism revenues.

Profitable business

Another Aeta leader, Paylot Cabalic, in an interview on May 17, said their guided treks had proven to be a profitable business, enough to pay for the education of Aeta children, including his own. Now both his kids are teachers in public schools.

A big chunk of the income goes to the students’ allowances, school fees and uniforms, while the excess are allocated to leaders and elders. They also set aside an emergency fund in case someone is hospitalized or dies.

Cabalic and Mangatoleran were among those who guarded the barricade to block tourists when the Inquirer went to the site last month.

Mangatoleran has three children who are about to enter high school in a few years and he wants them to graduate and achieve their dreams like Cabalic’s children.

“That is why we are here, to fight for the better future of our children,” Cabalic added.