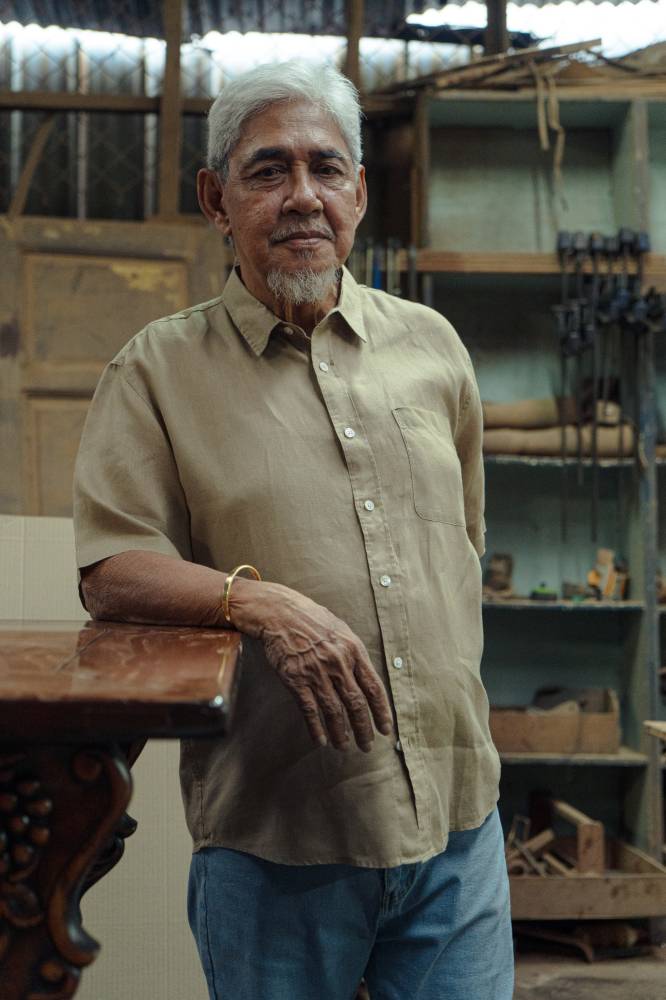

Buddy Lagdameo is Filipino furniture’s keeper

“I’m a professional basurero,” Buddy Lagdameo says, a wry grin spreading across his face. “We buy everything Filipino. We don’t touch anything that’s not Filipino. Whatever old Filipino furniture and artifacts we keep.”

He walks through the sprawling 3,500 sq.m. property, which houses his studio, shop, and warehouse.

Within the warehouse are towering wooden doors, ornate tables detailed with Spanish colonial carvings, and wood. So much wood. Ninety percent of which is recycled from old houses and fallen trees. “Real, hard, heavy, wood. No cheap stuff,” he says, running his hand along a Molave table surface.

In his studio, there is a collection of Mindanao fabrics and soft stone jars. Clustered in corners are just some of his collection of 300 bululs, carved Cordilleran granary guardians. A few of his 100 Cordilleran baskets hang from the ceiling. He even has a few eerie Kalinga headhunting trophies, blackened skulls staring from the shelf. Then there are Buddha statues from a period in the late ’70s, when he ran the house as an urban ashram.

Surrounded by his collection are Lagdameo’s furniture creations: tables, from consoles to dining centerpieces, flanked by elegant Kamagong chairs.

Besides being a collector and furniture maker, Lagdameo is also an artist, showing his carvings of a face emerging from Molave, spindly African-inspired pieces, another of a Buddha ensconced in an Enso, and three blind mice, side by side.

Lagdameo moves through the maze with the confidence of someone who knows exactly where everything is. Point to anything and he’ll tell you its story, its age, where it came from, and how much he paid for it. With a photographic memory, it shouldn’t come as a surprise, knowing his previous life.

The makings of heritage

For decades, from the late ’60s to the early ’90s, Lagdameo worked the trading floors, first at the Manila Stock Exchange, then Makati Stock Exchange. “That’s the training from the stock market. You remember the prices of all the stocks,” and so it reflects in his antiques.

“It paid the bills,” he says simply, and more importantly, supported his habit of collecting anything of Filipino heritage. His collecting started with dressing up his grandmother’s 1932 Bahay Filipino, nine-feet Capiz windows and all, which he still lives in today.

“The market was Monday to Friday,” he explains. “Weekends were something different.”

While other stockbrokers spent the weekends playing golf at country clubs, Lagdameo caught the evening bus to Baguio with his young family, then pushed deeper into the Cordilleras. He even kept a traditional Igorot house in Banaue, all stilts, no bathroom, as his base for collecting runs.

The family often came along in his Land Rover loaded with supplies, ready to set up tents with his wife, renowned Australian dress designer Rosalyn, and his three kids, including jewelry designer Natalya.

His affinity for the Cordilleran lifestyle and their rituals started as a 16-year-old, fresh from Ateneo, as he traveled up the dirt roads to the Cordilleras by bus, staying for months. From this first trip grew his collection of centuries-old wooden crafts, jewelry, and fabrics. “Maybe I was Igorot in a past life, because the connection is very strong,” he says.

Lagdameo recalls how he wanted his children to know the Philippines. While summers were spent in Australia, where his wife was from, regular weekends were spent exploring locally, from weekend road trips to heritage churches around Manila, or going farther to Banaue, Bontoc, Sagada, all the way to Lubuagan.

Preserving piece by piece

As Lagdameo collected antiques after trading hours, his collection grew. And so he established a system of runners, supporting their livelihoods with steady incomes in different provinces, “I had people working for me for 30 years until they died,” he says. “Now their children work for me.” From Quezon Province to Mindanao, these runners brought everything by boat, bus, and truck.

Lagdameo would buy first, ask questions later, as long as he had space. Which he did, until he didn’t. And by the early ’90s, his home was full, requiring the construction of the current showroom.

By the ’90s, those in the know were asking Lagdameo to help furnish their own homes, looking for the kind of heavy, well-made furniture that wasn’t as readily available in the commercial world. He also started buying old houses just to get the wood and the furniture.

Collecting had taught the heritage savant about proportion, materials, and how anything old Filipino could work in a new space. He recalls that his first set of furniture he created was made in his own backyard out of bamboo, then the cheapest raw material. His daughter Natalya chimes in, recalling how she had a mini scythe to smooth the fiber’s surfaces.

“I’m not learned. I didn’t go to school for this. It’s all experience and exposure,” Lagdameo says.

As a designer and collector, Lagdameo has become something of Filipino furniture’s keeper, a passion he hopes he can pass on. “Hopefully more young people can appreciate old Philippine furniture,” he says.

And in a world that is becoming increasingly filled with items that are mass-produced, Lagdameo reminds us that what lasts with true meaning is often heavy, handcrafted, and built to last.

“We buy everything Filipino. We don’t touch anything that’s not Filipino. Whatever old Filipino furniture and artifacts we keep.”