Norman Crisologo curates yet another f*ed up but brilliant show

If you want to see art that makes your skin crawl (but makes you think and look twice, too), go to an exhibit curated by Norman Crisologo.

This is the energy at “Ang Butas sa Lupa ay Butas ng Langit,” a group show that feels like a séance, a fever dream, a descent (or maybe an ascent). At first glance, the artwork looks straight-up messed up. But linger a little, and the show starts to unfold in a gloriously deranged, warped, and raw way that, like it or not, is unsettling for most.

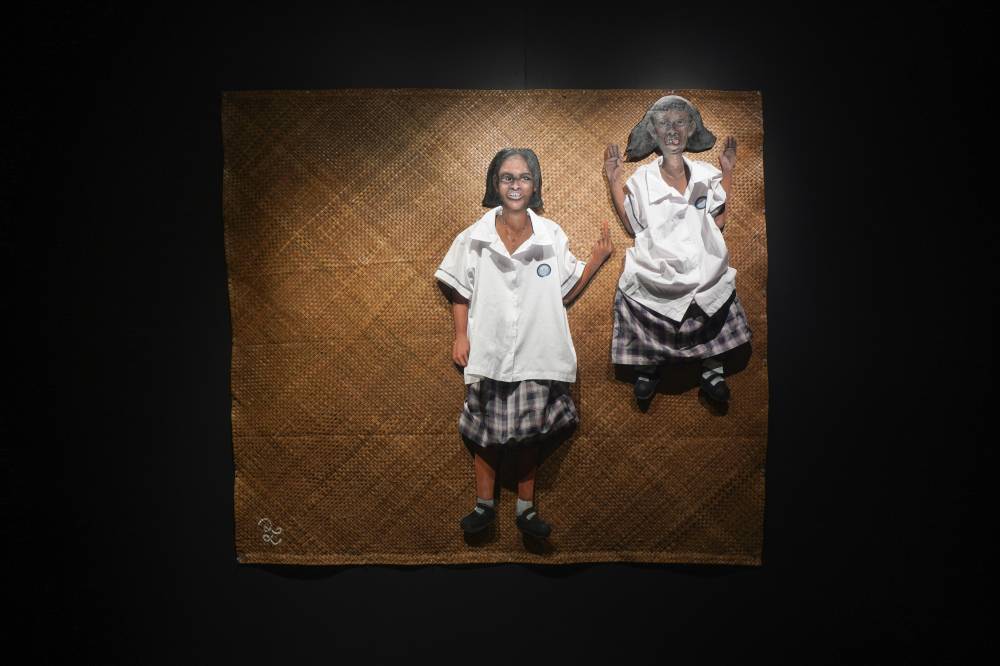

“Pasok po kayo,” the three-word exhibition notes by Lourd de Veyra reads at the entrance of the exhibit. The words are installed next to the first artwork you see, a pair of photographic works by Artu Nepomuceno. The ballerinas, captured under natural light, appear sublime, elegant, almost unreal. But this moment of grace quickly fades, and soon you’re stumbling into visions of decay, sex, death, purgatory, and utter madness. Maybe a little heaven but mostly straddling these worlds.

“The title says it all for me,” says Crisologo on his curation for “Ang Butas sa Lupa ay Butas ng Langit.” “Sometimes you see something that’s ugly or just a hole, but actually, it enters something heavenly. Everything is not what it seems.”

He says he wants the artwork to “talk or fight or love each other… Sometimes, you think they look good together,” he tells me, “but when they’re actually near each other, talagang nag-aaway. One eats the other. Or one lifts the other. Then when you add a certain color to it, parang marriage counselor—it brings things together. It’s funny how color does that.”

Crisologo curates the show with his signature walls painted in different colors. While in the past he painted the walls bright neon greens and oranges, for this exhibition, he painted the surfaces a range of grays and neutral tones. “I look at the works first and try to see which ones seem to be friends, and which ones need to be against each other,” the curator explains. “Then the color comes at the end, when I want everything to be one whole show.”

On choosing artists, he shares how he picks a style he likes. “I ask them if they’d like to explore that one artwork,” he says. “And then I say, let’s try to make it a bit bigger, smaller, or darker. I give them ideas. I don’t tell them what to do, but I just give them possibilities.”

Crisologo also shares that despite the darkness in the work that you would think would repel many, he also has the market in mind. And he knows the market well. “I’m a little bit business, a little bit art,” he says. “And I want to help them sell without selling out.”

So what’s in the show?

With a little bit of purgatory and a lot of possibility, the works are installed in a manner that makes you think twice about how to move about. I felt a compulsion, an instinct, that there was a manner to move through the show that maybe felt like the transition of heaven and hell, a shifting metaphor that is felt on Earth.

Near Nepomuceno’s work is a looming black-and-white work of Dennis Occeña. The gloomy hyperrealist painting features a man standing still before a closet, expressionless. Behind him, a woman’s head peeks out from the closet door. Flies buzz, in great detail, as if tangibly present.

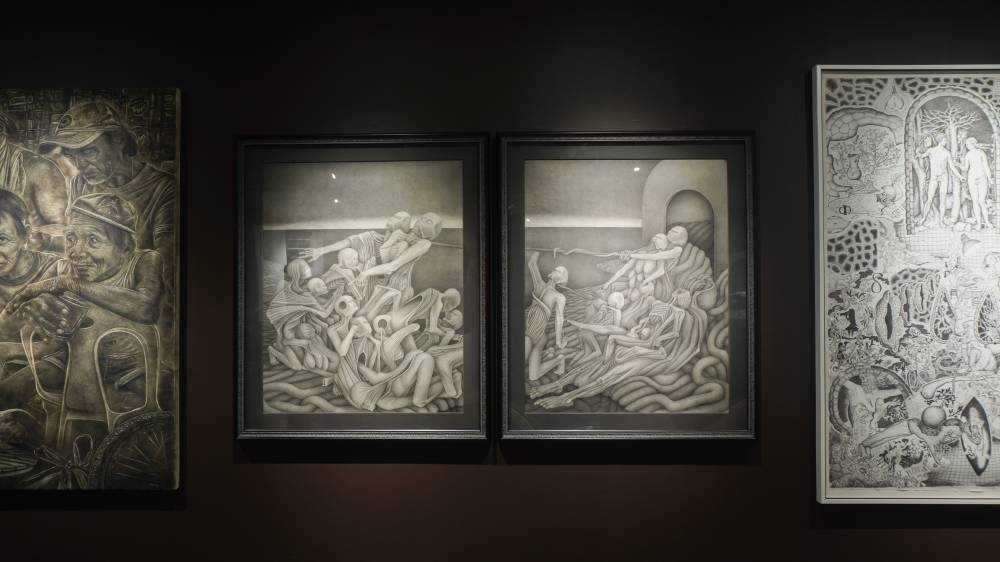

Next to the work is a pair of pieces by Karl Arnaiz, a self-taught artist from Talisay, Negros Occidental. Initially appearing to be paint, the works are technically well done in charcoal, graphite, and watercolor, depicting haunting renditions of men in the nude, lined up, then piled up, like offerings.

Further in, the works get more condensed. Soika’s “Abjectoons” combine the terms “abjection” and “cartoons” in images layered with symbols, faces, and other suggestions of the worst of humanity, in layers and layers of archival pen, thread, and aerosol paint.

David Ryan Viray also creates heavily layered images and goes full pen-and-ink apocalypse with historical, philosophical, mythical, and real-world references to war, territory, and religion, from depictions of what seem to be Adam and Eve to figures that seem to be from another realm—all rendered in dense detail.

Then there’s the collaborative works between two artists: the well-known jack of all trades de Veyra and educator Kaloy Olavides in ink, acrylic, and marker. The works sprawl, from images of Jesus playing basketball and bones on fire to evidently satanic goats, crucifixes made of bones, and middle fingers.

JC Mariategue takes us straight to what looks like hell. His installation sprawls across the wall, in a triptych-esque division of what seems to be heaven, Earth, and the underworld, bringing to mind Classicist religious panels or Bosch, this time appearing to be more focused on demons, not angels.

Jayvee Necesario sketches skeletal, humanoid forms that twist and snake like serpents. All sinew and no skin, amassed onto each other, the pieces feel like a descent into a fleshless, restless existence.

Ian Fabro, who regularly works with Crisologo, presents a Madonna-like sculpture cloaked in mesh, made of plaster, wax, preserved flowers and insects, and prayer medals, evoking religious imagery of the Holy Mother but under a darker lens.

Meanwhile, Gwen Fuji’s piece “Corpus Mundi (Body of the World)” features a massive painting of a voluptuous nude woman, her body resting atop a pile of unidentifiable limbs and bones, all set on a blood-red background.

There are also images recognizable in the Philippine context. Rap Carloto’s “Listen to what you’re seeing” paints familiar images of the city’s chaos—from the multicolored umbrellas on street carts to traffic signs—but accented with hollow-eyed bunny heads and blurred-out faces, evoking the urban with the strange logic of dreams.

Marvin Dalisay, who draws from his experience living in poverty, presents “Sapat Amon Sumsuman,” featuring images of men gleefully drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes on monobloc chairs, as corpses of dogs and pigs hang from hooks nearby. There’s a dog on the table too, which we tried to figure out for the longest time if it was alive or dead and ready to be eaten. The artist creates with the darndest mediums as well: fire, smoke, squid ink, and bird droppings.

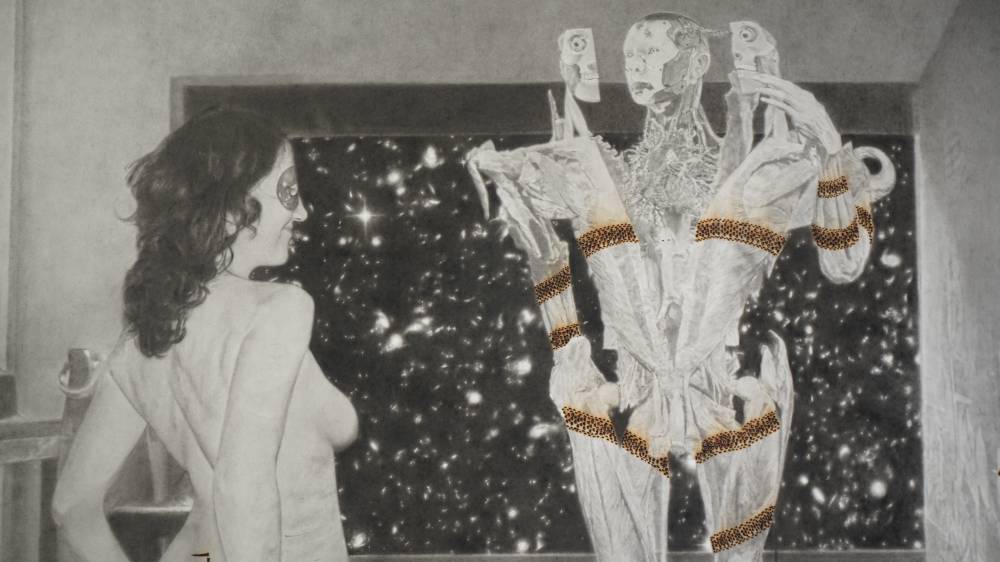

Further in, Rando Onia’s “Disco in Eden” involves a nude masked woman, and what might be aliens or robots in the studio, evoking a world that is warped. He continues to use fire, burning the canvas in his process.

Jomari T’Leon paints in his distinct style that is subdued yet contemplative, with somber undertones. Despite the flowers, the figure of a human wearing a silver crucifix lies under fabric, collaged with images of foliage.

Robert Langenegger, true to form, goes full depraved, as written in his artist bio, continues to create with “extremely confronting humor, carnal excess, body fluids and unclean protagonists.” You’ll know his work when you see it.

“It looks like a slice of normality,” Crisologo says. “But once you come in, you start seeing the artists’ pieces. I wanted it to be a bit of a journey. A portal maybe to heaven, to hell, to purgatory. Whatever… Every step, there’s something deeper and deeper. Or shallower and shallower. Little secrets.”

So what is “Ang Butas sa Lupa ay Butas ng Langit” really? A portal, a pit, or a mirror? Either way, you leave unsure of how you’ve been touched by this f*cked up universe of ballerinas, bunnies, corpses, saints, pigs, and prayers, which all coexist. And leave feeling unsure if you’ve been blessed or possessed. The latter more likely.