A matter of syntax

The opening lines of an E.E. Cummings poem have been gnawing at me all week. A week that saw journalists—the real ones, as well as the pseuds—come under fire, literally, in the case of the five Palestinian journalists assassinated in the double-tap missile strikes by the Israeli army on the Nasser Hospital complex in Gaza that also killed the civil defense workers and other civilians:

“since feeling is first

who pays any attention

to the syntax of things”

Odd lines to recall, I know, when thinking about the fallen journalists of Gaza, for the poem, one of Cummings’ most famous, speaks so obviously about the boundlessness of love. But then I thought of how love, and the act of opening oneself to love, is one of the bravest things one can do. And in being daring enough to love, one is being vulnerable and true.

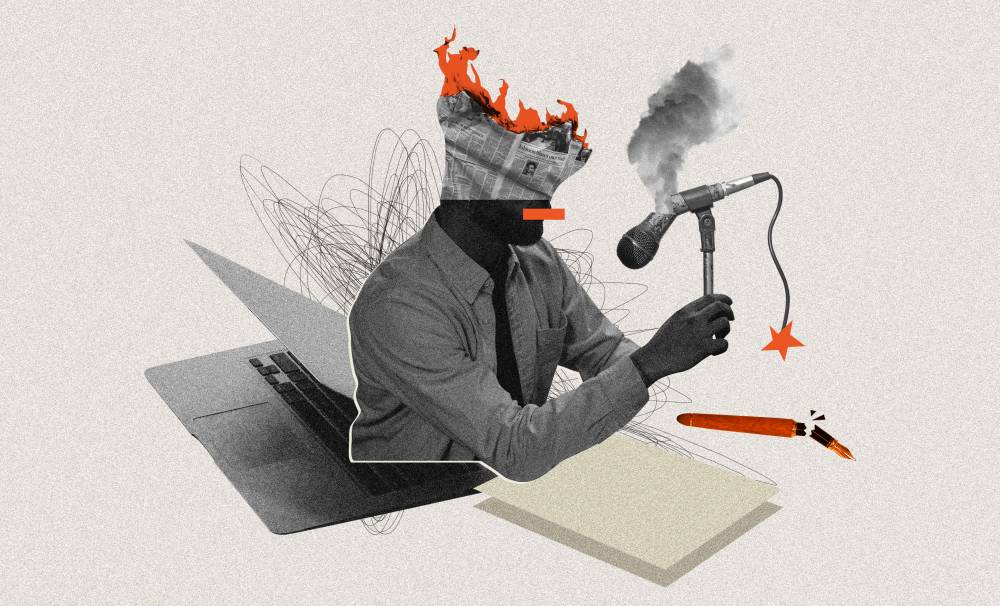

What it means to be a journalist

In a sense, journalism echoes this; the best journalists do what they do out of love (trust me, it’s rarely about the money). For the likes of Anas al-Sharif, Mariam Abu Daqqa, and Hossam Shabat, fully aware of the dangers they faced, they did what they did for love of country and for their fellow Palestinians, brushing their fears aside in pursuit of truthful reporting of the news. For this is what it means to be a journalist: to summon the courage to bear witness to reality, to remain unflinchingly faithful to the facts in the face of crushing devastation and horror, death threats as well as, increasingly, shameless propaganda and wanton distortion of the truth by other parties, and to strive not to lose one’s humanity in the process.

The primacy of feeling and the persistence of fact can often seem to be, in the practice of journalism, diametrically opposed to each other. Feeling, as the poem states, does usually come first—when encountering someone for the first time, for example, when arriving at an unfamiliar location, or when faced with a particular situation.

While feeling is instinctual, instincts can be way off-base. As the saying goes (usually uttered by self-styled enlightened liberals to MAGA sheep with impaired or nonexistent critical thinking faculties), “facts don’t care about your feelings.” Thus, while a feeling, a hunch, say, can lead to a story, a journalist’s report must necessarily be based on fact.

By this I mean objective, demonstrable, evidence-based fact, not both sides-ism parroted as performative fairness to manufacture consent for, in the case of Western legacy media these days, an ongoing genocide by Israel, abetted by the US, that has already slaughtered close to 300 journalists in Gaza, more than in any of the wars in the 20th and 21st centuries combined.

Facts, truth, and truism

There is fact, there are truths, and there is truism. In the course of my research into colonial structures and imperialism and their lingering impact on how histories are constructed, manipulated, and disseminated to a public unable—by design—to distinguish agenda from reality, I’ve come to understand that while truth is often held up as a universal value, the adherence to which is a kind of glue that holds society together, the definition of truth itself can be elastic, depending on who controls the flow of information, and who controls the narrative.

In fact (excuse the pun), truth is dynamic, relational, and contextual. In “The Politics of Truth,” Michel Foucault notably reflected on the political nature of truth, which opened it to distortion as well as amplification. He called truth “a thing of this world: it is produced only by virtue of multiple forms of constraint… Each society has its regime of truth, its ‘general politics’ of truth.” This then determines what is accepted as the truth, and how, and who are the gatekeepers of what is deemed to be true.

And when an occupying regime is deliberately targeting the truth-tellers, what does that say about their own relationship to the truth?

As for syntax, I’d argue that it matters more than ever for journalists. I don’t mean syntax in terms of grammatical construction, in the agreement of subject and verb, the placement of conjunctions and pronouns and the like, but in the flow of words and phrases to communicate the facts on the ground, simultaneously a desperate plea to the world to take urgent action to stop a genocide, and a rebuke in light of the same world’s bewildering impotence.

The poem’s ending is a fitting, if unwitting tribute to Gaza’s journalists, whose commitment to the truth lives on:

“And death I think is no parenthesis”

Not all journalistic battlefields are strewn with the burnt and dismembered bodies of children targeted by American-made quadcopters. Some are to be found in suburban garages filled with luxury cars purchased by contractors who have amassed wealth in questionable ways, or along ghost project floodgates that have collapsed under a torrential downpour.

A journalist always has a choice.