What if AI is better at governance than us?

Is artificial intelligence (AI) simply a tool or more sinisterly, an improvement—a replacement, even—for the human workforce?

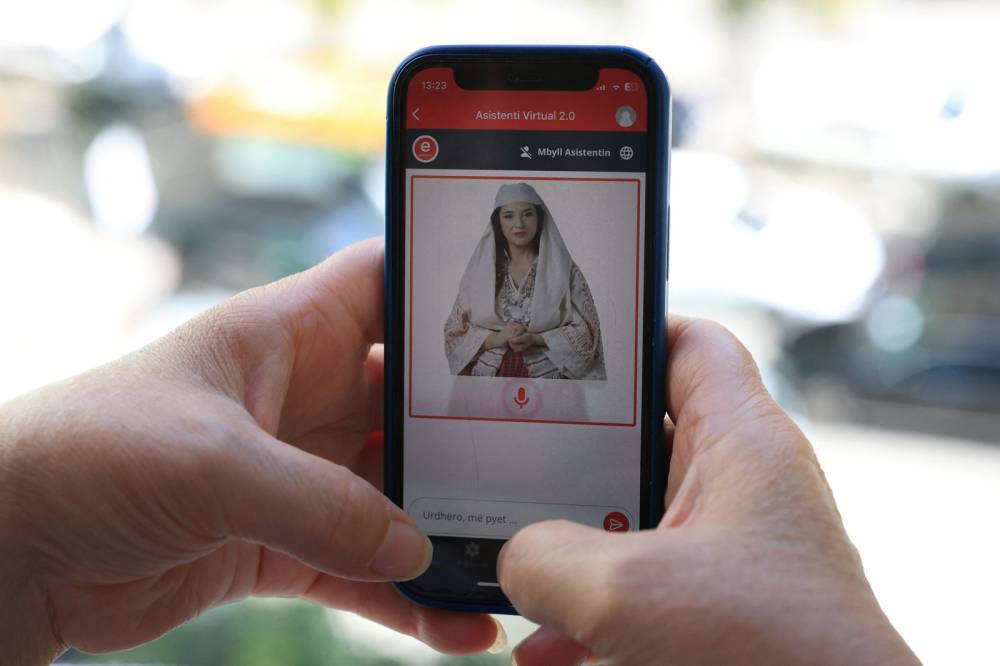

The role of AI and its place in society is a hotly debated topic, given its unprecedented rate of growth and evolution. But it seems that the issue now goes beyond its effect in education or even its potential to replace and effectively wipe out select professions. Case in point: Last Sept. 12, Edi Rama, the prime minister of Albania, introduced to the Albanian Socialist Party the first-ever AI member of government: Diella.

“Diella is the first [government] member who is not physically present, but virtually created by artificial intelligence,” says the Albanian prime minister. Diella will reportedly handle public procurement and make it “100 percent corruption-free,” and “every public fund submitted to the tender procedure will be perfectly transparent.”

Previously, the AI minister was introduced as the virtual assistant in the e-Albania platform, where it notably assisted Albanian citizens in accessing around 36,600 digital documents and 1,000 services, according to official statistics.

Though questions of accountability in the event of error or corruption, along with concerns surrounding who trains and programs the AI have since arisen, the unprecedented move reflects Albania’s long-standing battle with corruption in its administration.

Inhuman governance

Procurement, in the case of Diella, is factually defined as the collection of goods and services to achieve a desired goal. To bring it closer to home, an example of procurement is the identification and selection of contractors for certain flood control projects. In an ideal world, the criteria by which a construction firm should be evaluated should only involve its financial status, technical capabilities, and track record—not to mention the regular monitoring of a project’s progress.

Among the aforementioned, none require subjectivity like familial relations or even utang na loob. Instead, it relies on complete and utter objectivity that places procurement not as an act of governance, but rather, an administrative process that is based on facts, figures, and rationality alone.

We’re not talking about the creation and passing of laws rooted in deeply human experiences and needs. This is about a straightforward process that’s impaired by systemic corruption and the limitations of human cognition.

That said, wouldn’t it be to our collective benefit for matters such as these to be left to an unbiased, incorruptible body? Technological limitations, accountability concerns, and the loss of hundreds, if not thousands, of jobs in the bureaucracy aside—strictly looking at the billions of pesos lost to corruption and ghost projects yearly—wouldn’t an AI administrator outright reduce such incidents?

AI: A digital colonizer?

Although corruption remains abstract and insurmountable for some, it remains a human problem that must be addressed and resolved by humans alone. If not, wouldn’t it be the same as admitting we can’t be left alone to self-govern? That we need something else, someone who can make the decisions we aren’t capable of making for ourselves?

Sound familiar? President William McKinley once said: “We could not leave them to themselves—they were unfit for self-government, and they would soon have anarchy and misrule worse than Spain’s was… There was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them, and by God’s grace, do the very best we could by them, as our fellow men for whom Christ also died.”

Humanity’s relationship with AI is highly contested, complex, and one that will continue to develop and evolve in the coming decades. But whether you view it as a tool to be used or even as a social companion in rarer cases, AI, at its core, was an instrument created by humans for humans. And when it is replacing us not only in the workforce, but now in the government, that isn’t necessarily just indicative of the so-called dangers of AI—instead, it is actually more indicative of our capabilities (or lack thereof).

AI will inherently be better at administrative tasks, yes. But what separates us from a tool is our capability to discern and make decisions—and now that it’s proving it can also do that better in government, frankly, it only means our replacement is rightful and just.

Is that something that we should stand for? Undoubtedly not. But until we’ve proven our capability to self-govern—to avoid corruption at even the most administrative parts of governance—then we might as well accept AI as our digital colonizers.