Managing boundaries and consent

While watching some short films for a festival, I saw that a few of them credited theater actress and director Missy Maramara as the intimacy coordinator. I knew this was a new role in film productions in Hollywood—someone in charge of navigating what is acceptable and not acceptable when it comes to intimate moments onscreen, like, say, sex.

I had no idea that it was being done here, so I quickly messaged Maramara and asked to sit down with her to find out exactly what it means to be an intimacy coordinator and how she got started in the work.

“I heard about it, pre-pandemic, after my MFA,” she states. “I finished my MFA back in 2014. The prerequisite in theater was wala kang pake. Pag kiss, kiss. My training in the Philippines… when your director says to do it, you do it. If you’re not willing to push the boundaries that you have, you should reconsider your life in the theater.” She finishes the thought with an almost exasperated, “Ganon!”

Intimacy 101

As an actress, Maramara considers herself daring—always pushing her limits as part of her practice because of her training, but because she’s a teacher, she saw “the shift in the way students and the younger generation respond to training.” Thus, she became curious to explore it further. But there were no available mentors or training in the country, and she didn’t want to go back to the US to get it.

It wasn’t until the pandemic that she discovered an online course on Intimacy for Improv with Lucy Fennell (who has a range of credits in theater, film, and TV, including “All Of Us Strangers” and “Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story”). From this course, she learned the pillars of intimacy coordination in improv, along with names and concepts that inspired Maramara to seriously get into Theatrical Intimacy Education.

To get herself certified, she contacted Intimacy Directors and Coordinators (IDC), a New York-based organization that trains in intimacy coordination for theater, film, and television. She took the online courses, where she learned various concepts and did exercises through the eight-week-long, weekly sessions.

The experience was “very hard,” Maramara shares. “I was unlearning what I knew as an actor and coming to terms with it and aligning it with our Filipino culture because the modules were very Western.”

The five pillars of intimacy in the Philippine context

Because of that Western mindset, Maramara asked Ariel Diccion and Ron Capinding, actors and faculty members of the Ateneo de Manila University, to help her translate the concepts of the first two modules (covering the pillars of intimacy coordinating) into the Filipino setting and culture.

There are five pillars of intimacy in production, namely context, consent, communication, choreography, and closure. Maramara shares that she “had to translate consent. I had to translate what boundaries are.” I immediately caught on to what she meant, since respecting boundaries is uncommon in Filipino culture. Everybody is in everybody else’s business, prone to giving comments and criticisms to strangers, close friends, and family alike. No exemptions.

Maramara and Capinding adapted the concepts of context to kalagayan, saying, “It’s positionality—where are you positioned, what are your influences. It puts the actor in the center.” Next is consent, which they called kusa, or “of the heart.”

“Apparently, we don’t have a word for consent because we’re a colonized country,” they say, to which I immediately respond that studies and scholarly papers have shown that before our colonization, Filipinos never needed consent because we were very social and respectful people.

The rest came easier: komunikasyon for communication and koreo for choreography. For closure, they chose the word kalas, “which equates to breaking free.” And from Diccion’s analogy of the bahay kubo, Maramara was able to have a working model she could use in the Filipino setting. “It’s a shared space,” she says.

And she has a whole method that shows off the five repurposed pillars, adapted to our local culture and customs.

What it means to be an intimacy coordinator

As she was getting her Level 3 certification from IDC, she was also approached by Amazon to bring in two other people (she chose Jenny Jamora and Patty Lapus), who were working in the same field, for further workshops in Singapore to train with the Los Angeles-based Intimacy Professionals Association (IPA). This equipped her with more techniques and skills, and she was able to take all her learnings from her training and keep the best practices for the country.

She shares stories about her work in theater and in film (she has worked on the sex comedy “I’m Not Big Bird,” “Un/Happy For You,” and the box office hit “A Very Good Girl”). She’s been involved in Viva Max projects, “but only as a consultant, not a coordinator. I’m only a coordinator when I’m on set. As a consultant, I only give workshops.” In the past three years, she has been working in the industry, and she has had to untangle issues of power, power dynamics, and the differentiation of respect and trust, “which they always get wrong.”

For her, “the job of the intimacy coordinator is to help with the communication and the flow” of the actors, and for the director to navigate such intimate scenes. This is especially true when the power dynamic always skews toward the director, whom most actors would not say no to. That said, it’s her job to find out what the director needs from their actors and to empower said actors to be clear with their boundaries before they do any scenes involving nudity, intimacy, sex, or conflict.

Other than working with the actors and the director ahead of the shoot, the intimacy coordinator ideally also handles “community alignment, rehearsal—if there’s a budget.”

“On a different day, with the choreography of the scenes, I also talk to wardrobe. I also make sure [that no one’s] taking videos on their phones, that it’s a closed monitor, and ideally, in my practice, I do a closure exercise with the actors when they are done with the intimate scenes for the day,” Marmara explains.

On setting boundaries

All this seems pretty intense and tedious, but Maramara shares the benefits of the exercise. She says that when the actors feel empowered and they know their limits and boundaries, they are then “free to act and they won’t be pussyfooting around each other.” The scene can then reach its full potential.

“We’re not here to police anybody,” she says jokingly, “Ba’t kami mamumulis eh matanda na kayo. Intimacy coordinators are here to support you, to articulate your needs, articulate your capacities para walang hulaan para mag-save ng time. We provide intimacy riders, not just to protect the actors, but also the production house.”

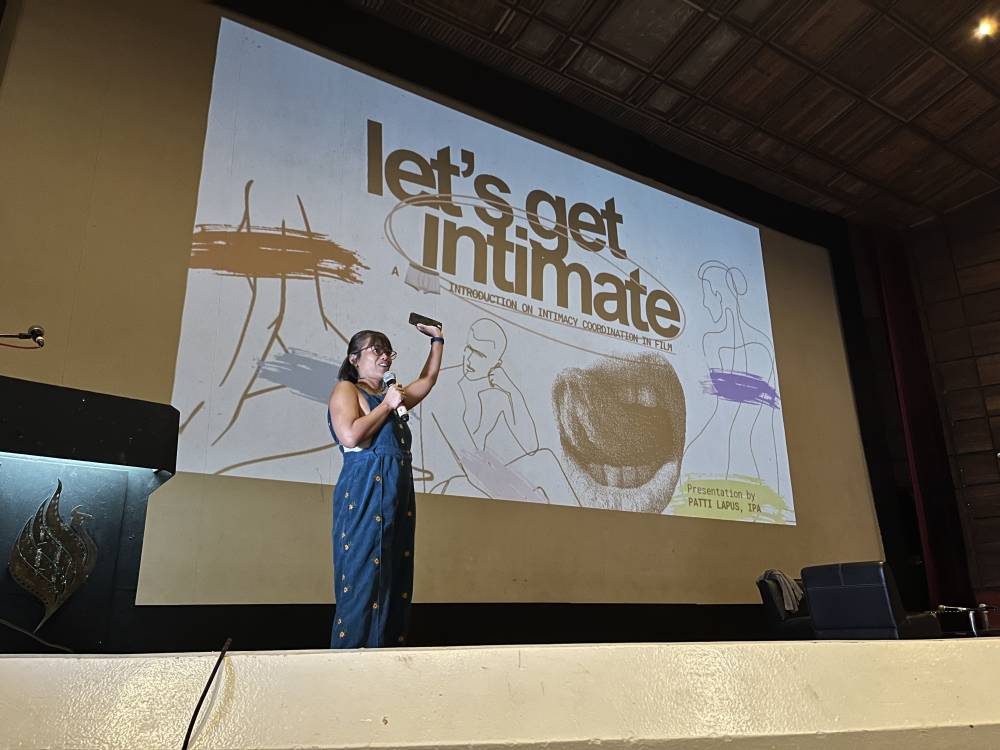

On Sept. 30 at the Future Filmmakers Forum—sponsored by the Directors Guild of the Philippines, the University of the Philippines Film Institute, and the film program of De La Salle-College of St Benilde—producer Lapus gave a talk on the importance of intimacy coordination.

She echoed a lot of the points that Maramara gives, including an understanding of the Filipino concept of boundaries as it is “shaped by our family, our upbringing, our religion, our political stance, and culture.”

“With our physical boundaries, we have a say kung saan ka puwede hahawakan. With our intellectual boundaries, we have a say in what we want to know or learn about. Our emotional boundaries dictate how we feel about a specific thing that happened in our lives,” Lapus explains.

The emphasis is always on the empowerment of the actors, the director, and the crew. And the overall point is to move toward safe and sustainable filmmaking practices for the industry. Lapus emphasized this at the end of her talk as she states, “Ultimately, the intimacy coordinator is not there to restrict creativity but to professionalize vulnerability.”