Worlds of history in a shawl

Lately, art has been pointing us forward. Many projects in conceptual art have been tackling digital or AI-driven possibilities. We are seeing many installations exploring decolonial frameworks. And exhibitions, especially in the Philippines, are generally asking big questions about identity, of self or of country, and how it links to the future.

While these dialogues matter, it’s worth pausing to look back at what we already have in the past, and appreciating it for its beautiful aspects, too.

Ayala Museum’s upcoming exhibition, “Mezcla: Interwoven Cultures and the Mantón de Manila,” proposes just this. With its elaborate floral embroidery, luminous silks, and cascading fringes, the mantón presents itself as it is: an example of straightforward beauty and excellent craft. But also layered with stories that span continents and time.

In collaboration with the Embassy of Spain, Instituto Cervantes, and the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID), the exhibition will run from Oct. 10, 2025 to Feb. 22, 2026. The show will bring together more than 38 mantones from the collection of Verónica Durán Castello, whose family heirlooms are at the core of the exhibit, ranging from rare 19th century examples to modern iterations.

The shape and history of elegance

With all its ornate embroidery, the mantón is romantic in spirit, practical against cooler weather, and historical in the way it stitched together continents. Square in form and folded diagonally into a triangle, the mantón de Manila was used to drape modestly over the shoulders.

In the Philippines, it sometimes completed the traje de mestiza worn by women in the Spanish colonial era. In Spain, it became a dramatic, luxurious accessory still seen today in Andalusian festivals and flamenco performances.

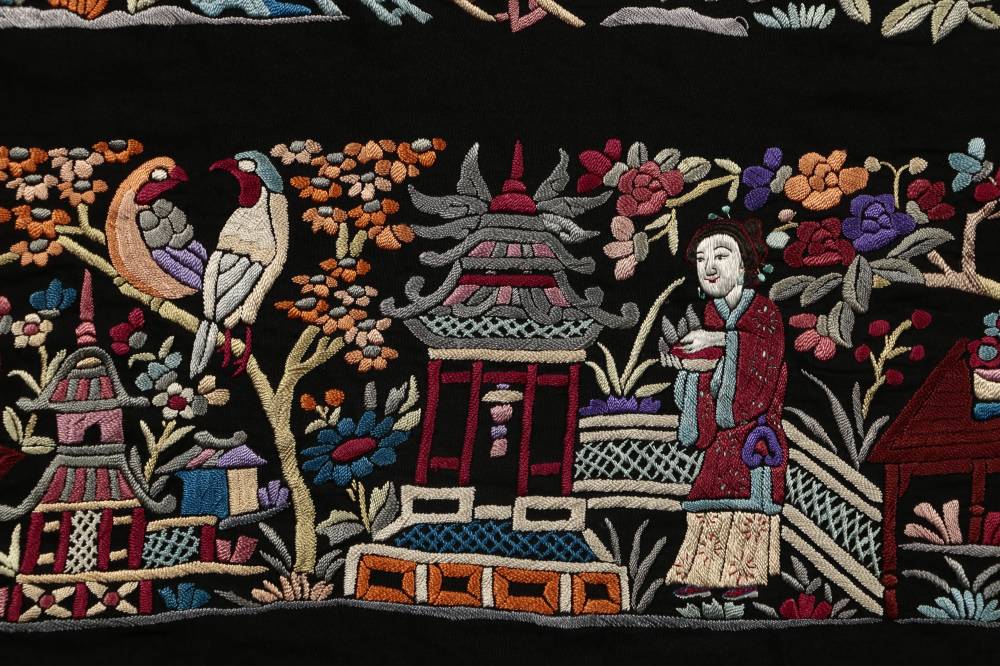

The pieces on display at the Ayala Museum carry images that remain familiar today. Stitched onto the shawls are subjects that range from the timeless attraction of flora to the charm of flitting hummingbirds.

Many late 19th century examples feature floral designs, each petal worked in varying patterns and textures. Others show Chinese motifs like pagodas and lotus blossoms that echoed the European craze for chinoiserie, a fascination with the so-called “Orient” that Edward Said would later critique as Orientalism. Unlike imagined fantasies, though, these motifs marked real trade routes and exchanges across Asia.

At the same time, the mantón reminds us of Spanish colonial rule, which shaped not just fashion, but Filipino life for centuries. While it is important and necessary to remain conscious of our position as a colonized people (and of its lingering repercussions today), it is also worth noting that Spain itself has long been subject to its own criticism through the “leyenda negra” or “Black Legend,” a narrative that exaggerated Spanish cruelty and decline. To dwell only on critique would flatten history; instead, the mantón lets us see the more complicated reality of a shared experience of beauty and creativity as well as exploitation and trade, all woven tightly together.

To have something known worldwide as the mantón de Manila is, in itself, something to be proud of. Just as “Manila envelope” or “Manila paper” are terms used worldwide, these ubiquitous terms point to a time when the Philippines was not peripheral but central in global circulation.

The mantón’s journey began as Chinese silk export ware, traded through Manila, ferried across the Pacific, and embraced in Spain as a marker of elegance. Yet scholars suggest that Manila itself shaped the garment, lending it its breezy fringes and knotted latticework. The mantón’s details echo local textile traditions and embroidery still practiced in Lumban, Laguna, today, too. In this light, the mantón is not simply a Spanish article of clothing but a very Filipino one.

A symbol in thread

First exhibited at Casa de América in Madrid, the collection now takes its place in Makati. Aprille P. Tijam, associate director and head of Exhibitions and Collections at Ayala Museum, describes the collection as “living witnesses to memories shared and exchanged between continents… where Filipino audiences can appreciate the mantón up close… reflecting the enduring nature of cultural exchange, then and now.”

“‘Mezcla’ is an important opportunity to show that the mantón de Manila is more than just an object of beauty, “[it is] also a powerful testament to the Filipino story as it unravels within a global narrative,” says Jorell Legaspi, senior director at Ayala Foundation.

Audiences can now encounter the mantón not simply as a relic of another culture, but through threads running back to our own local Filipino histories, with binding stitches of migration, trade, and excellent artistry.

The exhibition also invites visitors to participate in fun ways. An interactive section at Ayala Museum offers knot-tying through macramé, designs on paper, puzzles, and coloring activities, fun for both children and adults.

“Mezcla: Interwoven Cultures and the Mantón de Manila” runs at Ayala Museum from Oct. 10, 2025, to Feb. 22, 2026. Guests may walk in or book their visits online at ayalamuseum.org/visit.