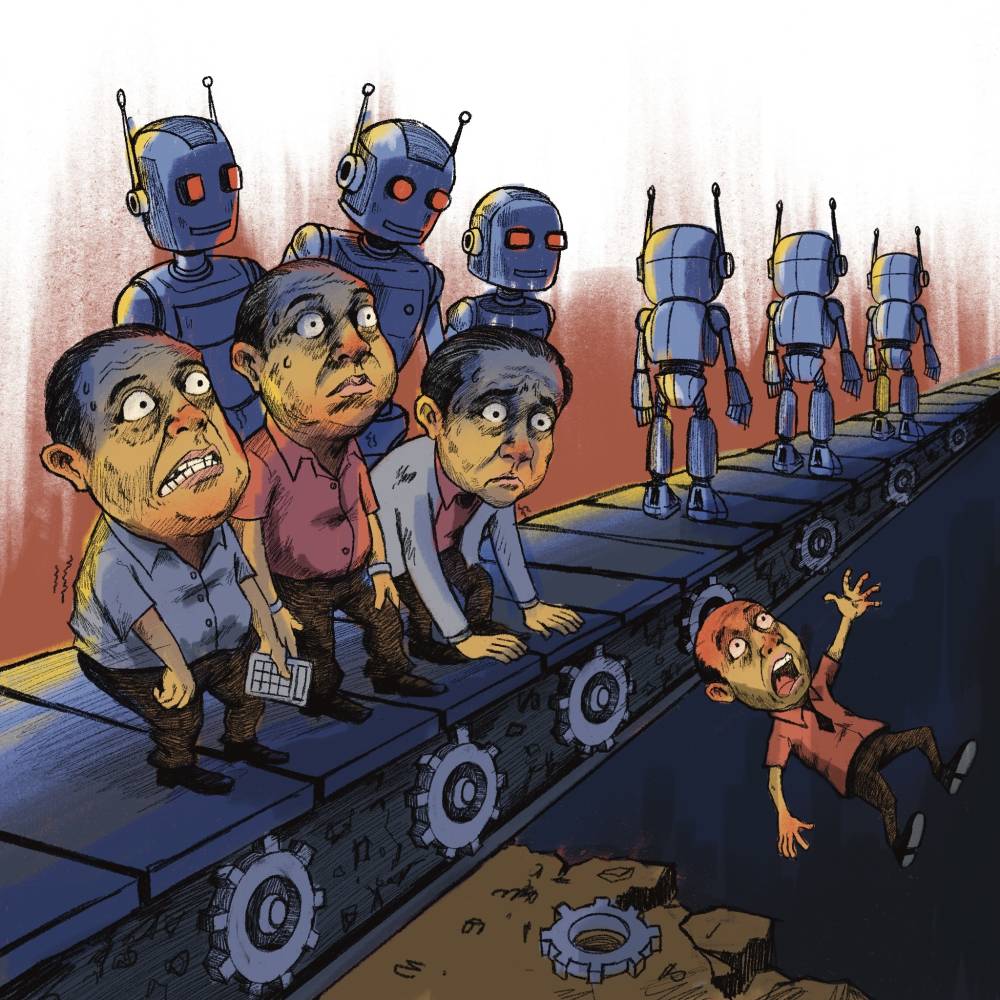

The bleak future of our atomized labor force

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) Artificial Intelligence (AI) Preparedness Index places the Philippines below the global median in readiness for artificial intelligence.

The index measures digital infrastructure, human capital, innovation and regulation. The Philippines performs moderately in human capital but remains weak in infrastructure and innovation.

The IMF also estimates that about one-third of all Philippine jobs are highly exposed to automation or AI-related transformation.

Exposure does not mean certain displacement, but it shows how much of the country’s labor structure relies on tasks that machines can already learn.

The institutions that adapt quickly to this shift will convert exposure into productivity. Those that remain rigid will convert it into obsolescence.

Education sits at the center of institutional challenge

Comparative evidence from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Program for International Student Assessment (Pisa) and World Bank learning reports shows that Philippine schooling remains heavily based on memorization and test performance.

Pisa 2022 placed the Philippines near the bottom in reading, mathematics and science, all of which measure reasoning rather than recall.

The World Bank’s assessment of learning poverty confirms that while enrollment is high, comprehension and analytical ability lag behind. Rote learning produces graduates who are diligent and accurate but hesitant to improvise or reason under uncertainty.

The system rewards obedience to process rather than engagement with ideas.

These habits of rigidity extend beyond schools. They shape how the Philippines regulates its professions and, by extension, how it organizes its entire labor market.

The country’s laws and regulatory systems are resistant to the cross-pollination of ideas and practices across disciplines. To practice a profession, one must first complete a narrowly defined, practice-oriented degree such as accounting, customs administration or criminology, fields whose core competencies are often better learned through experience. Then comes a single national licensure examination that determines one’s right to practice. Passing rates are kept low in the name of preserving quality, rendering the training of those who fall short economically futile.

The pattern feeds on itself

Professions that do not yet have their own governing laws lobby for one in order to create new boundaries.

Environmental planning, for example, began as an interdisciplinary field open to architects, engineers, economists and geographers. Over time, legislative prescriptions narrowed their scope rather than widened their reach.

The same logic now influences education. Liberal arts and humanities courses are being trimmed to make way for technical units, as if the capacity to connect ideas across domains were a distraction rather than a source of creativity.

The intent to raise standards is legitimate. But the means by which the system pursues it may be counterproductive. The creation of specialized degrees, exclusive licenses and narrow practice laws achieves uniformity at the cost of flexibility.

Instead of viewing professional competence as a continuum of progression, the Philippines treats it as a binary. One is either qualified or not. Other countries take a more fluid approach, recognizing partial credentials, apprenticeship and modular advancement.

The Philippine model remains locked to a single, highly specific academic path.

Accounting: What rigidity looks like in practice

Accounting is among the most structured professions in the country, governed by Commission on Higher Education Memorandum Order No. 27, Series of 2017.

When Salceda Research examined the approved curriculum subject by subject, a consistent pattern appeared. Roughly two-thirds of the coursework trains students in procedural or computational tasks such as financial reporting, cost accounting and taxation. Only one-third deals with interpretation, ethics or strategy.

These are the very areas least susceptible to automation, yet they receive the least instructional time.

The findings do not suggest that the degree has lost its purpose. They show that its strength, precision, has become its limitation. The discipline trains for exactness when the market now rewards interpretation.

Accounting, like most technical fields, is as much an art as it is a science. Its scientific side lies in method and measurement. Its artistic side lies in judgment, timing and intuition.

The more the curriculum drifts toward the former, the more it risks producing skills that AI can replicate.

Most model countries have already recognized this. In the United States, any bachelor’s degree qualifies for the Certified Public Accountant examination, provided the candidate completes the required accounting and business units.

In the United Kingdom, professional bodies such as the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants and the Institute of Chartered Accountants accept graduates from any discipline, and vocational certificate holders can progress through modular examinations.

In India, the Institute of Chartered Accountants allows direct entry immediately after secondary school, integrating coursework and apprenticeship.

Singapore still prefers an accounting-related degree but recognizes bridging programs.

The Philippines stands almost alone in making a specific academic degree a mandatory prerequisite for licensure.

Resistance to cross-pollination of ideas: Broader consequences

By defining professions in increasingly narrow terms, the country has fragmented its labor force into isolated specializations.

Each field is walled off from others that could enrich it. The economy gains experts but loses integrators, professionals who can move laterally, synthesize perspectives and innovate.

The result is a service sector of narrowly trained specialists who are efficient within their niches, but struggle to collaborate on complex, multidisciplinary problems.

AI amplifies this weakness. It automates the routine and rewards the interpretive. What will distinguish the most resilient professionals are the capacities that resist codification, including ethical judgment, strategic thinking and foresight. These qualities make technical disciplines humanistic and transform skill into creativity.

Machines can execute procedures, but they cannot weigh fairness, anticipate consequence or connect insights across fields. Professions that isolate themselves from one another also isolate themselves from the capacity to learn.

Professional fortresses will fall—not because they are weak

They will fall because the foundations on which they stand have become too narrow to support renewal.

Standards should remain high, but the path to meeting them must widen.

The better alternative to exclusivity is progression, a continuum of learning that allows professionals to grow through experience, apprenticeship and reflection rather than through a single credential.

The economy will need professionals who can cross boundaries, not merely defend them.

In every field, mastery will depend less on the perfection of rules than on the art of judgment.

(The author is a former congressman of Albay and also previously served as its provincial governor. He also earlier served as chief of staff of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo. Before entering politics, he was an award-winning stock market analyst who headed the Philippine research team of UBS and ING. He currently chairs the Institute for Risk and Strategic Studies Inc./Salceda Research.)