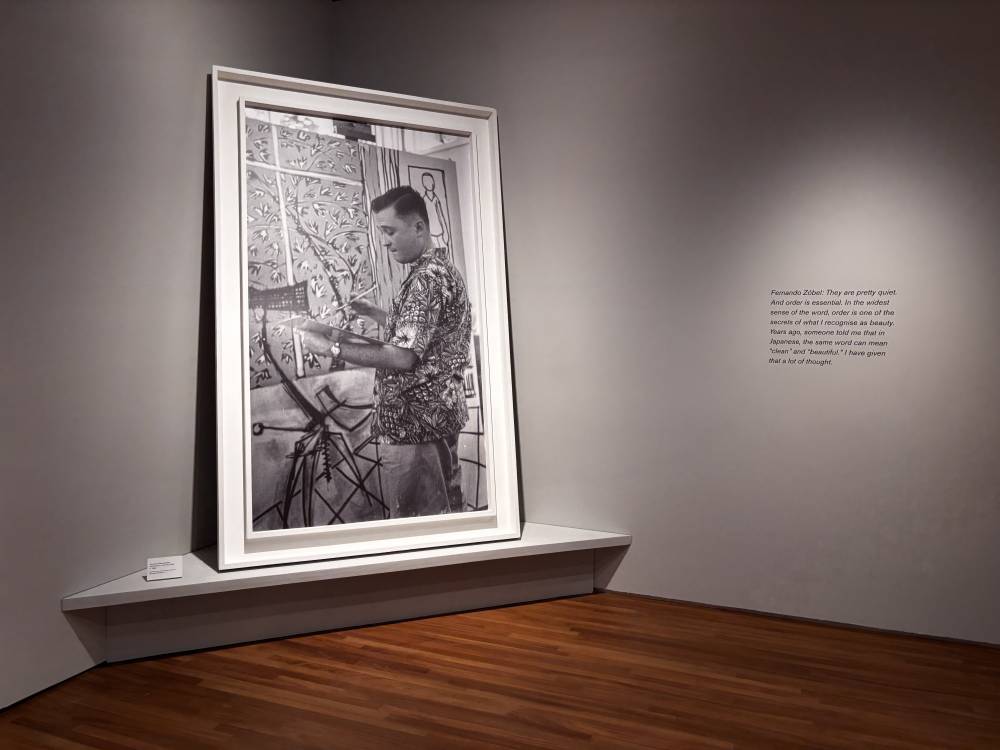

Fernando Zóbel’s many lives take shape in Singapore

When I first wrote about Fernando Zóbel, it was for a UP postgrad class under professor Patrick Flores, now chief curator at the National Gallery Singapore (NGS). It was an attempt at art criticism on Zóbel’s own written art criticism for a show by the Art Association of the Philippines in the 1960s. Back then, it was my first time to even encounter Zóbel as a writer, as I mostly knew him as a painter who globetrotted from country to country.

While the comprehensive exhibition, “Fernando Zóbel: Order is Essential,” is closing soon, at the end of November, it goes full circle, highlighting the multiplicity of Zóbel as not just a cosmopolitan artist but also a prolific patron, collector, and scholar.

Overseen by Philippine curators Clarissa Chikiamco and Patrick Flores, as well as Spanish curators Manuel Fontán del Junco and Felipe Pereda, the exhibit returns to Zóbel through material traces of a life fully lived across art worlds, constantly in motion across Manila, Madrid, and Massachusetts. Featuring over 200 works spanning paintings, drawings, prints, photographs, and archival materials, “Order is Essential” situates Zóbel as a “transcontinental modernist,” a figure who bridged cultures as fluidly as he bridged media.

“Zóbel was a thinker,” Flores tells me in our conversation at the Gallery. “He wrote a lot, and that kind of thinking, with his commitment to art history and philosophy, distilled into the work. He was a man of many sympathies, not only an artist but a patron, a writer, a traveler.”

The cosmopolitan artist

A Filipino family of four scuttles past Flores and me during our conversation. They have elated smiles as they “ooh” and “ahh” in front of old photographs and yellowing studies. The mother clutches her chest and sighs with passion in front of a “Saeta.” Her daughter leans on her shoulder, and they gaze at the painting together. Further in, the son excitedly beckons to his father to show him the fluid forms of Zóbel’s “Fútbol 14.” The two stand in front of the painting with approving, self-satisfied stances. They seem proud to see works by Filipinos celebrated in another country.

Nearby, a small group of young Singaporeans listens to a private tour, nodding attentively and asking many questions. A few older ladies who also appear to be locals move through the gallery, taking in each work at a slow, thoughtful pace.

For many Singaporean and regional audiences, “Order is Essential” serves as an introduction to Zóbel. “The level of awareness is not very high,” Flores admits, “but when people get to see the show, they appreciate it because Zóbel worked across continents, from Asia, Europe, and North America. He appeals as a cosmopolitan artist, someone who cannot just be confined to one place.”

The show’s title comes from a Zóbel quote, “order is essential,” reflecting a belief that beauty and serenity arise from control and structure. It also nods to his methodical working process, as Zóbel would often create multiple iterations of a single composition before arriving at what he considered resolved. His signature “Saeta” series, executed using a syringe without a needle to draw thin lines of paint, epitomizes that delicate balance between restraint and fluidity.

The exhibition as dialogue

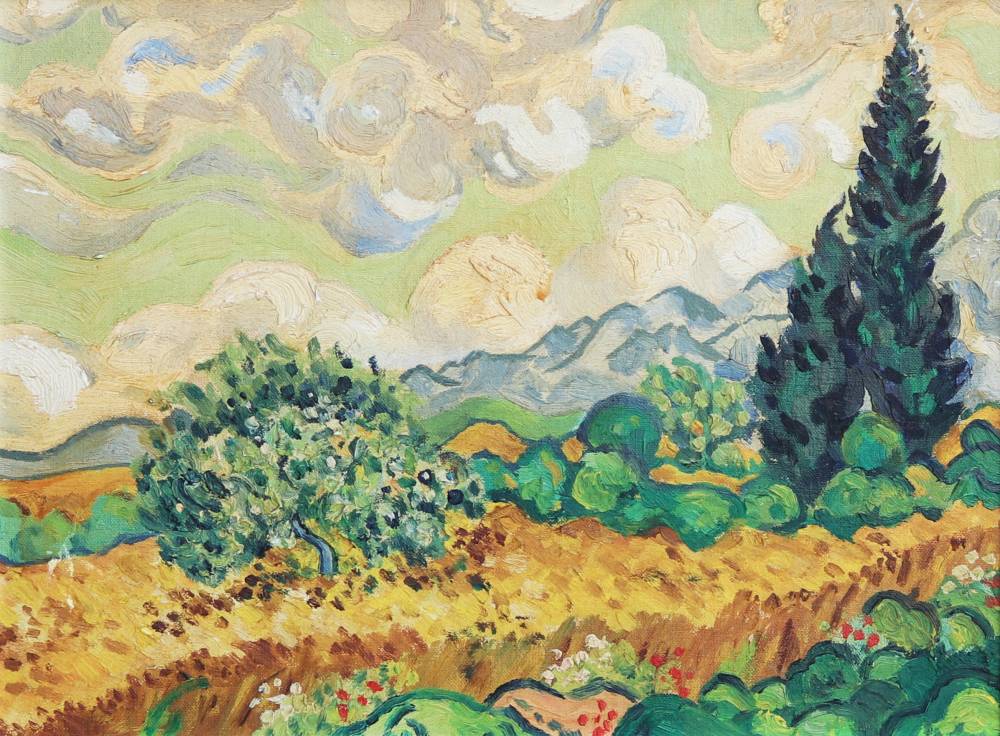

The show is spread across two galleries and five sections, each illuminating a different geography of Zóbel’s life. The prologue, “Half of this haunted monk’s life,” opens with two bookends: one of his earliest paintings, done in 1946, inspired by Van Gogh’s “A Wheatfield with Cypresses,” and his unfinished final painting, “El Puente (The Bridge),” created in Cuenca in 1984. Between them lies the yet unseen arc of his life and work.

Flores shared an interesting curatorial detail that the way this first part of the exhibition is installed with the framing, the walls, and the flow of sightlines, was designed to act like a bridge itself, connecting Zóbel’s earliest to his latest works.

Moving forward into “With every single refinement,” visitors are introduced to Zóbel’s early years in the United States, when he studied the humanities at Harvard and explored various visual art media without formal training. This part of his life is something not as explored as much in Philippine art history. Viewers see how Zóbel immersed himself with the vibrant art circles of Boston and Rhode Island, absorbing modernist tendencies from Rothko to Kline, with their actual works displayed alongside his. Nearby are works by Alfonso Ossorio, Zóbel’s cousin, who was also creating work on the East Coast at the time. Zóbel’s notebooks, portraits, and early sketches document his time as a young artist at Harvard who was, as Flores put it, “self-taught in art, but trained in the humanities.”

“He didn’t train as an artist in the fine arts tradition. Instead, he studied literature and history,” Flores says. “It was a humanistic approach to culture and art. This also explains why Zóbel couldn’t be easily confined to an art movement, because he wasn’t pressured to follow one or to learn under a mentor. He struck out on his own, learning art partly through art history and through looking at objects, because he was a collector.”

The section “Thin lines against a field of colour” brings Zóbel home to Manila, where he distilled influences from Philippine religious sculpture and calligraphy into abstraction. The “Saeta” paintings are here, accompanied by one of the actual syringes he used to paint them.

Nearby, abstractions by his contemporaries complement the work, such as HR Ocampo and Nena Saguil. “We wanted to give a fuller picture of Zóbel’s development,” Flores says. “So we added Filipino modernists who worked with him, as well as Asian artists he collected.” Ateneans will be well pleased to see a black and white photo of the Bellarmine building, and read about Zóbel’s years teaching at the university, as well as his formation of the Ateneo Art Gallery.

The rooms become steadily more spectacular. “Movement that includes its own contradiction” traces his Madrid years and the “Serie Negra,” Zóbel’s response to European Art Informel. Some may recognize his magnificent black-and-white “Icaro” or “Icarus,” a painting that has long been in the collection of the Ayala Museum. Photographs from this period, many shown publicly for the first time, reveal how the camera became both a compositional tool and a metaphor for perception for the artist.

Finally, “The light of the painting” situates us in Cuenca, where Zóbel formed the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español in the city’s hanging houses. Here, landscape and abstraction merge, with his stunning monochromatic canvases that evoke the natural environments, from the gorges to the valleys, and the banks of the Júcar and Huécar rivers, as Zóbel renders their motion through fine gradations of light.

Curating across borders

Flores explains that the Singapore iteration is an expansion of past Zóbel exhibitions, specifically “The Future of the Past,” which was shown at the Museo del Prado in 2022 and later restaged at the Ayala Museum in 2024.

“We wanted to give a broader context,” Flores explains. “Abstraction became the entry point because it’s something everyone can respond to, even if they don’t know Zóbel. And we also wanted to connect him to global modernism, which is part of NGS’ vision: that modernism didn’t only come from the West.”

This contextual rethinking reflects Singapore’s inclusive approach to art from the region. “The Philippines is well represented here,” Flores says. “Of course, there could be more, but Philippine modernism is one of the strongest in Southeast Asia. It’s almost natural that it’s part of the Gallery’s collection.” He adds that NGS has recently acquired works by women artists like Anita Magsaysay-Ho and Nena Saguil, “to address the gaps created by the patriarchal nature of the earlier art world.”

A closing conversation

As our conversation winds down, Flores reflects on what curating teaches him that scholarship alone cannot. “In academe, you don’t get to see the work firsthand. But when you curate, you handle it, you gain intimacy with the material, and you see how the works relate. With Zóbel, I rediscovered the primacy of drawing. We often think of him as an abstractionist, but drawing is his foundation.”

Zóbel’s art, like his life, is a study in crossing borders, disciplines, and identities. He was a bridge, quite literally, like his final painting, “El Puente,” which depicted the bridge near his Cuenca home, suspended between stone and sky.

Standing before it, I thought of Flores’s words: “He was a bridge between cultures, between modernism and the world.”

And I thought of my old paper on Zóbel’s writings, the artist as critic, as thinker, as teacher. To see his work now, framed within a Southeast Asian museum that welcomes multiplicity, is to see the full resonance of that lesson: that art, like life, is most meaningful when it transcends the expected limits of one’s own making, reaching beyond the self, to connect with the world and others.