Don’t lose sight of the forest for the trees

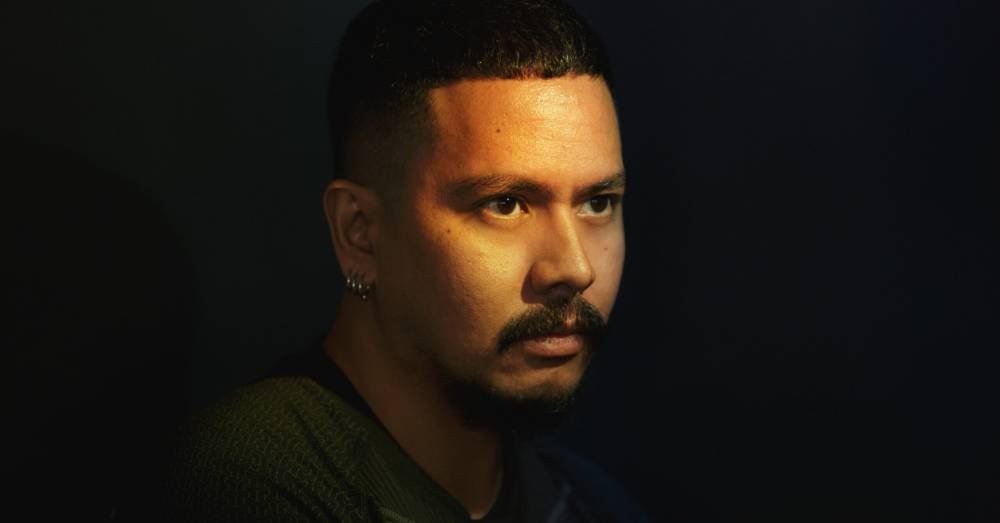

Don’t lose sight of the forest for the trees” is an age-old adage reminding us to notice the small details. Yet how often do we, among all creatures great and small, get caught up in daily life while overlooking the bigger issues, especially in the natural world? Derek Tumala’s work calls us to pause and reflect on our place in ecology with his latest installation, “Garden of Others, A Tree Grows” at Ayala Museum’s OpenSpace.

Since its renovation, Ayala Museum’s OpenSpace has been a spot where pedestrians pause and art lovers venture to encounter installations that merge the city with art. Recall James Clar’s looming giant parol, transported through highways from Pampanga. Or how about Ronald Ventura’s painted Porsches, the sports cars alongside his distinct black and yellow sculptures?

At present, the museum features a work by Tumala, which is not such an imposing sculpture in scale but instead a gentle, ethereal presence, guiding viewers back to nature.

Hanging from metallic grids—a recurrent material choice of the artist—laser-cut acrylic leaves with dichroic film move with the breeze, shimmering and shifting colors. Sunlight plays on them by day, while lights bring out hidden details at night. “I wanted to soften it somehow,” Tumala says.

The visual artist, whose work spans technology, sculpture, and deep ecological research, is clear about one steady inquiry in his practice: How do we live with nature? And as a subquestion, why have we spent so long pretending we’re not part of it?

“This work is about monumentalizing the other,” Tumala says, his voice calm but firm. “And the ‘other,’ for me, is nature… I grew up believing that nature is separate from us. But as I embodied my work, I realized we are nature. Nature is beautiful. It’s harsh, it’s immeasurable… It is within us. It’s not the other.”

In Tumala’s vision, nature is both the “other,” something we often treat as separate or distant, but rather, a mirror that reflects ourselves. By observing the living world with care, we begin to see that we are not apart from it, but intimately connected to it.

An introduction to othering

The installation opened last Nov. 13, after careful testing of the sculpture’s structure (especially after the recent typhoon Uwan). The installation comes at a timely point, like a meditation on ecological care.

Tumala cites British filmmaker Derek Jarman, who famously cultivated a weed garden at Prospect Cottage while sick from AIDS, letting unwanted plants thrive. He recites Jarman’s poetic words from his journal:

“The dew of the garden was mixed in the morning with the sweet fragrance of his memories.

The flowers are his mouth, the breeze his breath, the rose had been moistened by the dew of his cheeks.

Therefore, I love gardens madly, for at all times they make me remember him who I love.”

Tumala’s reverence for tending what others discard once previously expanded into a foraging project in La Union from 2023 to 2024, supported by the British Council and immersed in Emerging Islands. “We worked with communities, we foraged weeds,” he shares. “We explored weeds as a form of othering… what does it mean for something to be unwanted when it’s part of an ecosystem?”

He explained further, “We worked with a remote community and their local university, expanding the idea of weeds as a form of othering. In the Western world, colonial gardens and castles were manicured, with grass in neat squares and only selected plants. These aren’t viable for wildlife. By contrast, parks in Berlin, for example, are wilder in their culture. They allow nature to exist freely.”

“We don’t advocate enough for nature. Even weeds… It’s nothing to us. It’s just there,” he sighs. “Imagine if corporations started thinking we need more parks. That alone would change a lot.”

Tumala credits Ayala Land for being one of the few developers that consistently incorporates public green space. “They built Greenbelt, they keep cats around. Even that already says something about valuing living beings,” he says.

Mindful installation

You might recall Tumala’s jaw-dropping installation, “A Warm Colored Liquid,” a six-meter-tall sun made of steel, recycled abaca paper, and solar-powered lights for Art Fair Philippines in 2024.

He stresses the collaborative nature of his practice in general, which is occasionally made on monumental scales. “I work with engineers, museum teams, fabricators… I’m strict with the vision. If they say it can’t be done, I’m always like, ‘No, we can do this.’ I want to have that integrity of the work.”

While “A Garden for Others” is designed to withstand the elements, the more fragile appearance conveys a sense of vulnerability, almost as if a metaphor for the precariousness of life itself.

Assistant curator of OpenSpace, Marie Julienne “Jei” B. Ente, underscores the complexity of installation, used to working with installing these exhibits outdoors. “Every component is considered,” she says. “The work must withstand high winds, rain, and even earthquakes, all while preserving the artistic voice.” It is a delicate negotiation, much like the relationship Tumala explores between nature and humans.

A life connected

Tumala’s sensitivity to the “other” is rooted in early life experiences. Both of his parents were farmers before moving to Manila. His father became a history teacher who surrounded their home with encyclopedias that Tumala devoured. While his mother is a fashion designer, who passed down an aesthetic sensibility. “I saw how hard it is to grow crops,” he recalls. “That exposure sparked my interest in understanding ecosystems and life cycles.”

Extensive travel has also clearly shaped his perspective. In 2025, he exhibited at the Ljubljana Biennale of Graphic Arts in Slovenia and the Basel Academy of Art and Design in Switzerland. Residencies in Manila (including the Manila Observatory), New York, Korea, and grants from the UK deepened his research-based approach. In 2024, he was a CCP Thirteen Artists Awardee.

These residencies exposed Tumala to the many ways these developed cultures implement basic care in urban planning. He talks about parks in Europe and how, “It’s very dark at night for the trees,” he explains. “There are no lights. They think about trees, how they react to light, and how they coexist. Here, we don’t really have that conversation.”

The “other” as a mirror

“Garden of Others, A Tree Grows” comes across as a gentle, yet insistent critique of cultural neglect, as well as a visual reminder for passersby that urban spaces and society at large could, and should, integrate the living world more thoughtfully.

Tumala’s luminous forms invite viewers to witness the “other” without dominating it, observing gently, with care, attention, and empathy.

“If we see every living species, the weeds, insects, wild animals, mountains, trees, oceans, and humans, as important, then we can create a world that cares. Each and every one of us is precious and precarious,” the artist implores. “I want to express a call to action that we demand care for nature and for all of us.”

In Tumala’s vision, the “other” is not distant. It’s us. And through art, he offers a rare chance to see ourselves reflected in the living, breathing world around us, where every living thing matters and everything deserves to stay, with shimmering leaves that seem to suggest not to lose sight of the forest for the trees.

“Garden of Others, A Tree Grows” runs from Nov. 13 to Dec. 7, 2025, at the OpenSpace Front Plaza in the Ayala Museum.