Unearthing the fire beneath pibil

As I traveled through Mexico for my culinary journey called “Kitchens of the World,” chasing its most honest and soulful flavors, I found that some of the country’s most delectable masterpieces are buried beneath its soil. Pibil is one of those legendary dishes. It comes from the Maya word pib, which means “buried.”

For the dish, the meat of choice—usually pork—is marinated in achiote (or what we know as annatto), sour orange, garlic, and local spices, then wrapped in banana leaves and slowly cooked in an underground oven lined with hot stones.

It is ceremonial cooking—smoky, fall-apart tender, and perfumed with citrus, aromatic leaves, and special varieties of wood, made extraordinary by its contact with the earth and time.

It takes a village

Pibil is more than food; it is family, community, and ancestry.

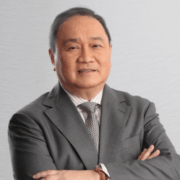

We had the pleasure of spending the day with Mayan chef Wilson Alonzo in Yucatan. Hailed as Best Chef in Yucatan for years, he is also the holder of the Guinness Book of World Records for the largest serving of cochinita pibil at 6,626.15 kilograms—over six tons!

Our day began with a visit to the local market, where we picked the freshest produce for our pollo pibil. Upon stepping into the chef’s outdoor kitchen, there was a lightness in the air, a feeling that something beautiful was about to happen.

Music was playing: soft, joyful, and grounding. There, we prepared pibil as it should be—as a community. That day, we became a part of his tightly knit kin. We pounded spices, roasted vegetables, juiced oranges, and helped him light the fire of the pib. Everyone had a task to help prepare our meal—from appetizers to the main dish; we cooked as one, with purpose, amidst happy chatter, while swaying to the tunes.

The aroma that wafted through the air was unforgettable—thick with the smell of the many dishes we were cooking. As the stones glowed, it was time for the pibil to be one with the earth. We witnessed Alonzo lower the cazuela to the pib, the underground oven—an act that ties him to his ancestors.

Hours later, he unearthed it. The smell that rose from it was pure magic—it was smoky, a memory to last a lifetime.

A feast for the senses

Wilson’s pibil is deeply Yucateco: bright with citrus, warm and rounded with the flavors of achiote, and rooted in tradition. In his hands, the pib is more than a cooking method—it’s a way of honoring his land, heritage, and everything that came before him.

There was something ancient in the way he moved and carried himself. Chef Wilson’s every step felt sacred: from the gathering of the leaves and tending the fire, to his blessing of the ground by making a sign of the cross with salt, sealing the pib, and even the uncovering and unearthing of the edible treasure that emerged hours later from the ground.

For Wilson, pibil is family. It’s something passed down—learned by watching, listening, while growing up inside the rhythm of a Mayan kitchen. He often says, “The earth cooks differently when you respect it,” and you feel that truth in every bite.

Different indeed. We feasted on the dishes we prepared—a symphony of flavors unraveled—all uniquely its own. Bright, earthy, smoky, and deeply comforting. The pollo pibil was a dream. Tender, fragrant, with hints of citrus and that light lacing of achiote that seeped into every bite of the meat.

Our sopa de lima (lime soup) was light and clean. The broth was lifted by the perfume of lime. The crisp tortilla strips gave it texture. Meanwhile, the sikilpak offered a nutty, roasted depth from the pumpkin seeds, which was made mellow by the addition of tomatoes and the warmth of chile.

Polcanes de toczél, a dish made with white corn dough (masa), stuffed with ibes—local white beans—deep-fried until golden and crispy, was a joy to make (and eat). And in between, we had a bite of xec, a citrus salad made with their native oranges. It was sweet, tart, and lightly herby all at once, and it cleansed our palates.

The Dulce de Siricote y Papayas, fruits gently cooked in sweet syrup, made a dramatic finish to our unforgettable meal. The fruits were served covered with a native gourd. When it was lifted, the smell of burning rosemary smoked the fruits, and the smoke gave it drama.

Of tradition, history, and newfound friendship

As I think of the meal that was—I remember it as honest, grounded, and distinctly Yucatecan. It was a celebration of land, history, and newfound friendships.

Chef Wilson is a custodian of recipes passed down through generations. He sees it as his duty to let his ancestors live on by carrying their traditions forward and sharing them with a new generation. This is why he dreams of opening a school—a place where their memory, their stories, and their flavors can continue to thrive for generations to come.

He shared his special cochinita pibil, hoping that by cooking it ourselves, we can stay connected through food.

Cochinita pibil

Ingredients

2kg pork ribs

4kg pork leg

2kg pork loin tip

1kg pork knuckle with skin

180g red achiote recado

8g black pepper

5g allspice (or Tabasco pepper)

5g cumin

5g oregano

30g garlic

100g white onion

150g pork lard

Salt, to taste

350 ml sour orange juice (if unavailable, substitute with

250 ml sweet orange juice + 100 ml lemon juice)

Procedure

1. Cut the pork into even pieces (preferably fist-sized for more uniform cooking).

2. Prick the meat with the tip of a knife, rub with salt, and let rest for about 3 hours.

3. After resting, blend all remaining ingredients and strain.

4. To assemble the cochinita, line the baking dish with toasted banana leaves.

5. Place the pork pieces—preferably the bone-in cuts at the bottom—into the dish.

6. Pour in the red recado mixture, making sure to coat and massage the meat well.

7. Add enough water to bring the liquid level up to the surface of the pork. Adjust salt.

8. Bake for 3½ hours (or until the meat is fully tender) at 250°C.

9. Serve with pickled red onion salsa.