An Emman Atienza Law won’t save us

Trigger warning: Mentions of suicide

A little more than a month ago, as I write this, Emman Atienza died by suicide. She doesn’t explain why, and we’ll never know the reason—absent a note, letter, or status message in the wake of her last moments.

But she did have a history of attempts. She even mentioned in her last public Instagram broadcast message in September that she wanted to take a break from social media, and that she had been receiving death threats from so-called DDS (Duterte die-hard supporters). While it’s important to note that we’ll never find out if those people were the reason, her final act did spread the message of choosing kindness.

As an attempt to remedy the online plague of cyberbullying (and probably also because he gets cyberbullied in the public social media spaces he frequents), Senator JV Ejercito filed what he named the “Emman Atienza Bill.” It was meant to target online hate and harassment.

Of course, the fervor over protecting people’s mental health on the internet only lasted for a very short while. Up until the next issue du jour popped up, which is every other day here in the Philippines at this point.

Last week, model and actress Gina Lima died in a controversial fashion. Her death, a certain Valentine Rosales very publicly claimed, was at the hands of Lima’s ex-boyfriend, Ivan Ronquillo.

But the autopsy showed that whatever bruises Lima had on her body didn’t kill her. And because of the swift backlash Rosales’ accusation caused toward Ronquillo—as should be the case for a double domestic violence and murder case, had it been true—the ex-boyfriend died by suicide as well, professing his enduring love for Lima.

Now that the public reaction had turned on Rosales too, he now asks for the same thing Atienza wanted from everyone: to be kind.

Modern Filipino culture isn’t kind

Let’s be honest: An Emman Atienza Law wouldn’t save us. The rising number of suicides will not stop the tide of hate and bullying that seems to be ingrained among Filipinos at this point.

Filipinos love describing ourselves as “warm and hospitable,” but the truth is, we are not kind, and we don’t know how to be kind. A week after Atienza passed away, I wrote about the capacity of Filipinos to be nice in the context of unrelated scenarios, but since then, I’ve found the real answer to be troubling.

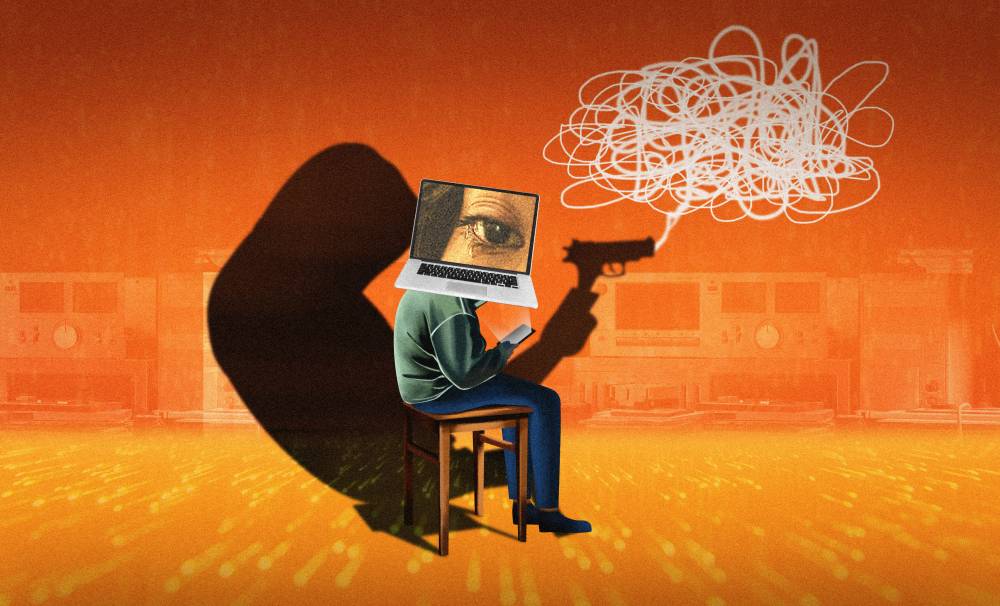

We are a loaded gun of hate, shooting all the time at anyone we can hit—all because it feels good, and much better than the sorry state of affairs that we live in. Access to the internet and social media being the new town square makes it easy to throw stones, and anyone can be a witch who’s tied to the stake in the middle of the plaza.

New statistics released by local market research agency Tangere found that seven out of 10 Filipinos have reported experiencing bullying—both online and in person. Eighty-six percent of that bullying is verbal abuse, because it’s the easiest to do. Fifty percent is social bullying, while cyberbullying was at 33 percent—though I wouldn’t be surprised if that last bit was underreported.

Our conservative, chauvinistic, patriarchal, and neocolonialist culture also bakes in the judgment and discrimination of people who challenge the status quo—the order of tradition and the values that are associated with it. Everyone’s required to be perfect in appearance, status, and actions, and anyone who doesn’t fall in line becomes a prime target for hate.

It doesn’t help that from 2016 to 2022, we were ruled by a president who embodied all the worst possible traits a person could have, which allowed the resentment that was overflowing to finally burst out of the pot and gave people license to be as terrible as they could be.

And they still are; half of us have still sworn loyalty to that man and see no problems being the worst scum of society, while the rest of us are only fighting back because the high road doesn’t get you anywhere.

What might actually save us

But the truth is, we’re all really just being beaten down by the upper class, and the hate we feel is a resentment toward life here in a broken country.

Everyone is mad because we work so hard and nearly kill ourselves to experience even the tiniest shred of comfort. Those who aren’t lucky enough actually do work themselves to death, while chasing stability and trying to beat an unjust system that has cornered them (depression also has economic factors, after all). Many have even joined the side of the system, because the only way up is to sell out and lick boots.

What might save us—and by saving us, I mean solving the problem of hate in the Philippines—is better living conditions, not just punishments for bullying and harassment. And that starts up top: get rid of the people who are milking us dry (which are half the population’s idols), hold them accountable, and redirect the funds they were stealing to make everyone’s lives better.

Then maybe, perhaps in a generation or two, most likely more, we could possibly fix the black heart of Filipino society. Maybe people would finally stop acting out when there’s no more boot crushing them underfoot.

Maybe life for many could finally get better, and people could finally stop being dicks, and there wouldn’t have to be another Emman Atienza giving away their life because everyone else couldn’t regulate their emotions.