How imagination can shape an archipelago

Tasha and Bella Tanjutco started Kids for Kids 10 years ago in 2015, when Tasha was 15 and Bella was just 13. “We were kids talaga when we started it,” Tasha recalls. What began as two teenagers trying to make sense of their advocacies has since grown into a well-known, youth-led movement centered on culture, climate, creativity, and children’s rights.

Today, they work with young volunteers aged 15 to 21, inspiring a new generation of climate-conscious changemakers.

“The goal really was to show kids you didn’t have to have that much money or resources to make a difference,” Tasha says. “It was whatever your community had, and you could build off of, as long as you were creative.”

Where it all began

Their early years were spent working across communities in Laguna and Manila, often responding to typhoons and relief efforts. When the pandemic hit, everything moved online. This shift opened their eyes to the breadth of the youth climate network already out there.

For example, they connected with young organizers like Gab Mejia and Issa Barte of For the Future, who were exploring culture-based climate solutions. While collaborating with various groups, it became clear that youth climate work was thriving. It just needed more bridges.

Tasha herself studied fine arts at UP Diliman. “I’ve always been drawn to art and design because growing up, that’s what I was exposed to,” she shares. “I originally wanted to be a cosmologist because I was fascinated by the sciences, our climate, and the environment.”

“I didn’t realize that people aren’t going to resonate with stories in a Times New Roman paper, but if I present it in an artwork, people are going to be interested,” she adds.

Tasha and Bella’s advocacies trace back to their grandfather, National Artist for Architecture Francisco “Bobby” Mañosa, who built a life designing in a Filipino manner that was never westernized or borrowed. “My sister and I grew up understanding that we were proud to be Filipino,” Tasha says. “And we realized this was not the case for so many young people because of the harsh realities they were facing. So the whole goal was to unpack these harsh realities together, and to build a community.”

Roots of Filipino design

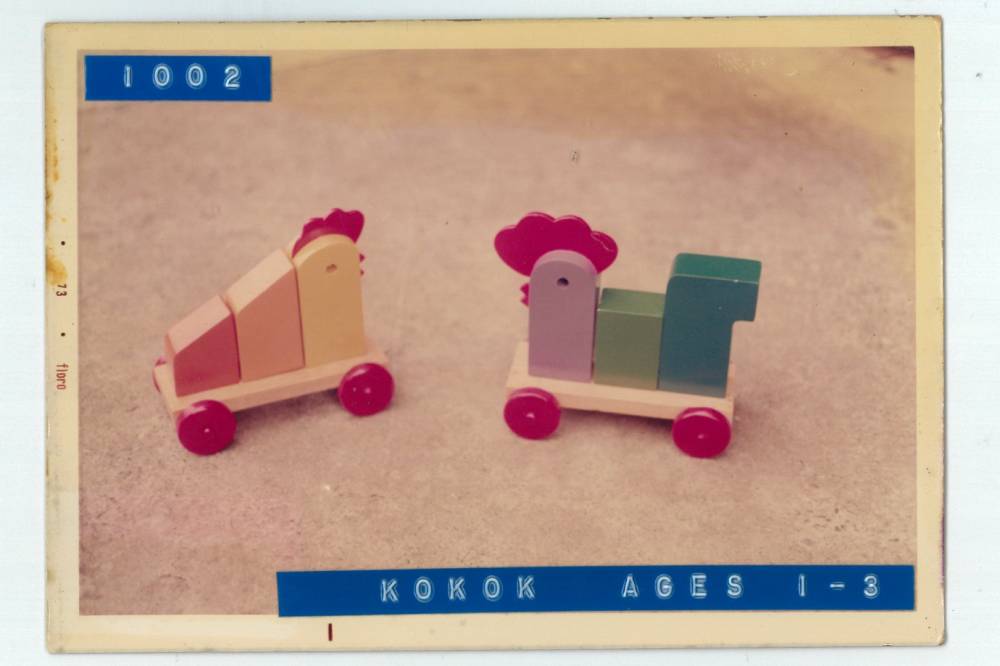

Their family’s design DNA extends far beyond architecture. In the ’70s, during the import ban, Arch. Bobby Mañosa, together with his sisters, began crafting Filipino children’s toys that were both culturally rooted and globally relevant. They attended expositions in Germany, saw the massive gap in non-toxic, design-forward toys, and realized they could fill it.

There was a seesaw that doubled as a furniture piece. “Tipaklong,” and “Manok,” grasshopper and chicken-themed wooden toys. These handcrafted pieces were sold at a toy shop called Dimples in Greenhills, right beside Tesoro’s, which some of you may remember.

This ethos of culturally grounded design has continued through Tukod Foundation. Established in 2000, it’s described as “a vision of a Philippines that championed its vernacular architecture, culture, and identity so greatly,” while “never afraid to call something, ʻFilipino.ʼ”

“What we wanted to really do is to craft a foundation that liberates accessibility to Filipino creativity to all generations of Filipinos,” Bella explains.

One of their initiatives is placemaking—building spaces rooted in Filipino identity, beginning with schools and child-centered environments.

This effort now leads into Tanaw, Tukod’s first annual supper club and silent auction in partnership with León Gallery and TOYO. Running from Nov. 22 to Dec. 13, it features five original Bobi Toys sculptures from the Mañosa archives, now one-off, signed, large-scale pieces inspired by the toys.

More importantly, the Tanaw fundraiser is for and with the communities with Bayay Halian, a climate-resilient school, creative space, and community kitchen in Siargao.

Building on Halian

Halian, a remote island between Dinagat and Siargao, has been a partner community of Kids for Kids since 2019. The Tanjutco sisters’ work began early on, with needs assessments, workshops, and long conversations with residents. But over time, it became a space where local culture, notably not outside ideas, shaped the solutions.

“We’re just feeding them the tools with something that the rest of the world can learn from,” Tasha says.

The turning point came after Typhoon Odette. After the typhoon, they conducted immediate relief efforts such as restoring the fishing industry, running a year-long feeding program, and repairing damaged classrooms.

“When we began these simple initiatives, the islanders themselves started championing their own initiatives,” Bella says. “They started marine conservation efforts, now recognized in local policy, and began teaching other islanders in Siargao.” In fact, today, Halian has its own fish bottling industry, something the residents built themselves.

But challenges remain. DPWH repairs took about four years for basic construction. The sisters recount how the school buildings leak through the lights, while the ceilings collect mold. “The kids are constantly mopping,” Bella says. “This island has so much hunger for education and so much passion to preserve its environment and its culture. They really need a space and a school to foster that creativity. We believe that the Filipino child deserves better.”

Together with in-house architects Bea Rodriguez, Bea Carague, and Janelle Gan, the sisters are now co-creating what they believe a Filipino public school should be, especially in remote islands, with Bayay Halian.

“Together with the teachers and students, we’ve been conducting needs assessments, learning their culture, to co-create a school that will really help the child grow,” Bella shares.

They’re mentored by architect Angelo Mañosa of Mañosa & Co. and architect Dong-Ping Wong of Food New York. “This is basically a proof of concept of what schools should be like in the Philippines and different islands, all inspired by the neo-vernacular architecture our lolo would always speak about,” Bella says.

Made beautiful by the vernacular architecture inspired by the local environment, the vision includes community kitchens to strengthen local livelihood, multiple play and third spaces for children, structures sturdy enough to become evacuation centers, with hope for makeshift libraries.

Legacy, carried forward

Listening to the Tanjutco sisters speak at Alma in Poblacion, originally a Spanish restaurant founded in Siargao, it feels like a full circle between the city and the island.

Soft-spoken yet well-spoken, while dressed in ethereal piña, the sisters recount how they met chef Luis Martinez in Siargao during the lockdown. These are just one of the collaborations that have formed bridges, going even further to the mothers, fisherfolk, teachers, and young people on Halian island.

Through Kids for Kids and persistent efforts, relief efforts have formed relationships and, in turn, led to these shared visions.

If Arch. Mañosa designed Filipino life through architecture, music, toys, and joy, his granddaughters are designing the same future, now through community, climate, and the creativity of children.

But Kids for Kids does not bank just on nostalgia either—it sets its sights on continuity. They embody a living lineage shaped by our local islands, design, and youth, anchored by the hopeful belief that imagination can transform an archipelago.

The silent auction, hosted online by Leon Gallery, will be open to the public from Nov. 22 to Dec. 13. Bidding will be conducted through the Leon Gallery portal at https://leon-gallery.com/auctions. Proceeds from the auction will directly fund the Bayay Halian project.

For information on donation packages and to contribute, please visit the Tukod Foundation website at tukod.org or contact Charlotte Vicente for donation inquiries at charlotte.vicente.tfi@gmail.com or +639989728799