How the Philippines forestalled its own development–and how we may redeem it

“Victory is claimed by all, failure to one alone.” –Tacitus

In Morong, Bataan, stands a $2.3-billion cathedral to futility.

The Bataan Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP) is complete. Its reactor vessel sits in place. Its control room is intact. The Philippine government spends P50 million a year to maintain it. It has never generated a single watt.

Filipinos finished paying for this plant only in 2007, more than 30 years after construction began.

The total repayment reached $22 billion, extracted from taxpayers who received nothing in return but the privilege of watching their neighbors industrialize while the Philippines endured blackouts.

The thesis is uncomfortable: The Philippines did not miss industrialization because of fate. We missed it because of decisions, each one rational in its moment, but disastrous in its cumulative effect.

I will not assign blame to the Presidents. But incident must be assigned to someone and I will assign it to the President under whose watch each failure occurred, regardless of who caused it. This is the burden of their office.

Under Ferdinand Marcos Sr., the BNPP was built at a very steep cost. Under Corazon Aquino, the completed plant was mothballed and the power crisis that followed was allowed to fester.

Under Fidel Ramos, the blackouts ended, but at the price of independent power producers (IPP) contracts that haunt consumers to this day. And, a profitable National Steel Corp. (NSC) was sold to traders who destroyed it.

Under Joseph Estrada, the momentum of recovery from the Asian Financial Crisis was broken by political scandal; while Thailand and South Korea bounced back with growth rates of 4-10 percent by 1999, the Philippines drifted.

Under Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, the NBN-ZTE broadband project was scuttled amid controversy, a $329-million investment that would cost billions more to replicate today.

Under Benigno Aquino III, chronic underspending led to the country ranked last in Asean-5 for infrastructure spending despite the cheapest borrowing costs in a generation.

Under Rodrigo Duterte, the response to COVID-19 came days late and then lasted months too long; the Philippines endured one of the world’s longest lockdowns, longer than Wuhan’s, yet suffered a 9.5 percent gross domestic product (GDP) collapse, the steepest since records began after the Second World War.

This exercise in diagnosis is important to charting our future, because the effects of these mistakes tend to accumulate and solving their predicate problems requires knowing these roots.

The Constitutional Straitjacket

The 1987 Constitution was written in the revolution’s afterglow. The framers looked at the cronies and concluded that foreign capital was the vector of corruption. If Filipinos controlled the economy, Filipinos would be protected.

This diagnosis was understandable. It was also consequential in ways the framers did not intend.

The Constitution embedded the infamous 60/40 rule, allowing foreign investors to own at most 40 percent of any business in designated sectors.

The framers believed they were protecting Filipino workers from foreign exploitation. In practice, they created a system where domestic gatekeepers became unavoidable partners for any foreign investor seeking market access.

If a foreign company cannot own more than 40 percent of a Philippine enterprise, it needs a Filipino partner. Who has the capital, the political connections and the regulatory relationships to serve as that partner? The beneficiaries are the established families who become gatekeepers to the Philippine market.

In 2024, the Philippines attracted $9.4 billion in foreign direct investments (FDI). Vietnam attracted $28 billion. The World Bank has repeatedly flagged the Philippines as the most restrictive country for FDI among the Asean-6.

To be clear: ownership restrictions are not the sole cause of lagging investment.

Red tape, high electricity costs and infrastructure deficits all contribute. But the 60/40 rule created a specific mechanism (mandatory partnerships with domestic gatekeepers) that extracts rents from foreign capital while providing little in return.

Bataan

The BNPP was conceived in the 1970s as the Philippines’ answer to the oil crisis.

The project was troubled from the start. A 1979 safety inquiry revealed over 4,000 defects. The plant sits on the southwest foot slope of Mt. Natib, a volcano just 30-kilometers south of Mt. Pinatubo.

But here is the fact that complicates easy judgment: the plant was finished. After construction resumed, it was completed in 1984. All that remained was to load the fuel.

Then came April 1986.

Corazon Aquino had just taken power. Halfway around the world, Chernobyl exploded. Within days, the new administration decided to mothball BNPP.

An International Atomic Energy Agency advisor, brought in by the Aquino government, raised concerns about welding, base plates, pipe hangers and transmission cables: quality control issues that, according to available records, were never definitively resolved.

The decision involved genuine uncertainty. Proponents argue the plant was built to international standards; critics point to documented defects and the volcanic location that Pinatubo’s 1991 eruption would later validate as a legitimate concern.

What followed the mothballing was not uncertain at all: the Philippines ran out of power.

From 1989 to 1993, Filipinos experienced eight -to 12-hour rolling blackouts.

The plant would have supplied one-third of Luzon’s electricity precisely when the grid collapsed. Economic losses reached $3 billion annually. And still the bills came due.

Fidel Ramos inherited the blackouts and ended them through emergency contracts with IPP. But the cure came with a price Filipinos are still paying.

The take-or-pay provisions guaranteed IPPs payment whether or not Napocor needed the power. The contracts were denominated in dollars. By December 2004, NPC’s long-term IPP obligations stood at $13.62 billion.

In 2024, Filipino households pay roughly 22 cents per kilowatt-hour (kWh). Vietnamese households pay eight to 10 cents. Filipinos pay two to four times what their neighbors pay because of contracts signed in desperation 30 years ago.

The cruel irony: in 1992, Westinghouse offered to settle for $100 million in cash and credits if the Philippines would borrow $400 million to repair and upgrade BNPP. The facility would be operational by 1995. Net cost: roughly $300 million for 620 megawatts. Ramos rejected this deal. Whether the plant would have operated safely is unknowable. What we know is that the alternative proved ruinously expensive.

Iligan Steel

The story of NSC is more painful than BNPP because NSC was not a failure. It was a success that was dismantled.

The Philippines was the second country in Asia, after Japan, to build a steel manufacturing plant.

By the 1980s, NSC had become the 11th largest corporation in the Philippines and the first government-owned enterprise to achieve ISO certification. It held 62 percent of the domestic market for flat steel products.

In 1991, NSC earned P538 million in net income on P12 billion in revenues. Its 4,000 workers received a minimum salary of P14,000 per month when the national average hourly wage was P9 to P20.

NSC was, by any measure, a well-run government corporation—proof that state ownership need not mean inefficiency.

In 1995, President Ramos privatized it. The President said the government “ain’t supposed to run a steel company.”

The winning bidder was Wing Tiek Holdings of Malaysia, a trading company with even less experience running a steel mill.

The key problem was that while Wing Tiek was in the steel industry, they were traders, not makers. Top management had no idea how to run a steel mill.

The CEO commuted to Kuala Lumpur rather than relocate. Planning meetings ceased. The government, which retained a 12.5-percent stake, should have seen from the start that the buyer lacked operational expertise.

In 1996, the best year for the Philippine economy in that decade, NSC posted an unprecedented loss of P2 billion.

Wing Tiek was sold to another Malaysian trader, Hottick Investment, which borrowed $800 million to complete the transaction, just in time for the Asian Financial Crisis to devastate its balance sheet. Cumulative losses reached P8 billion before the plant shut down in 1999.

Today, NSC’s 450-hectare facility in Iligan stands abandoned. We now import almost all of our finished steel products.

Leapfrogging strategy

Yet amid these failures, another path was being mapped quietly in the background by Jose Almonte and the Peoples 2000 group.

I have often asked myself: Who is our Goh Keng Swee?

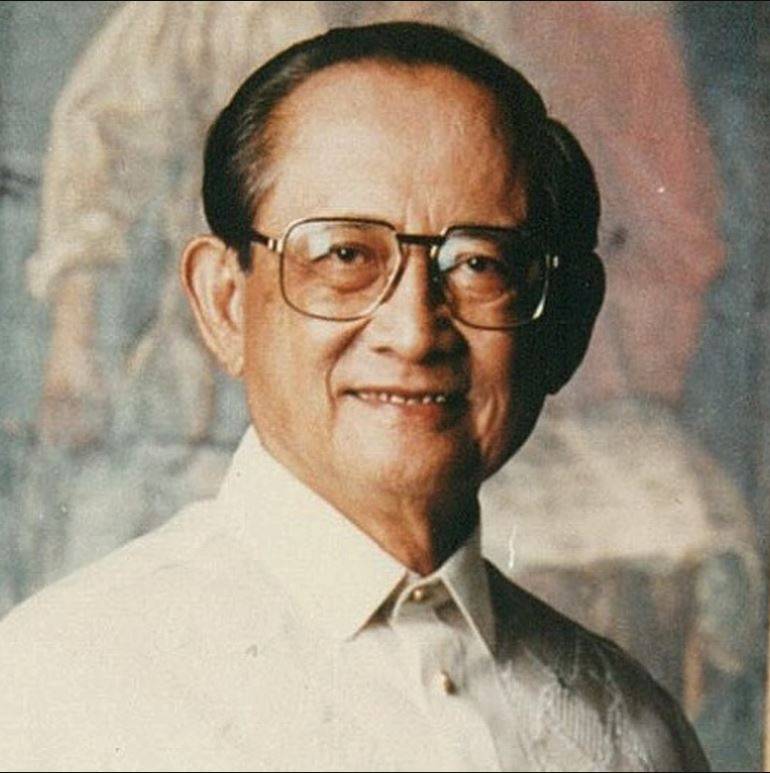

Singapore had its architect of industrialization, the man who built the Economic Development Board and the Jurong Industrial Estate, who transformed a resource-poor island into a global city. If we have anyone of that scale, it may be Jose Almonte, my fellow Albayano.

Almonte was National Security Advisor under Ramos. He understood that Philippine security could not be separated from Philippine development.

He assembled a group of reformers who called themselves Peoples 2000 and they started with telecommunications, the most visibly broken monopoly.

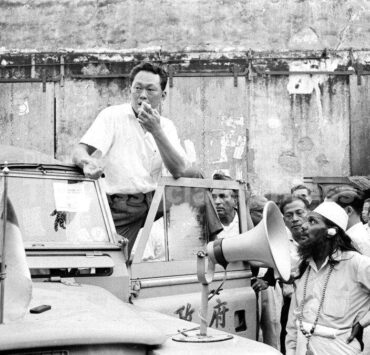

In 1992, it could take 15 years to get a landline in Metro Manila.

Lee Kuan Yew captured the absurdity: “Ninety-eight percent of Filipinos are waiting for a telephone, while the other two percent are waiting for a dial tone.”

Using executive power, Ramos broke the monopoly.

The lesson was not that telecommunications should be unregulated. The lesson was that monopoly power, left unchallenged, will serve itself rather than the public.

Breaking monopolies required using state power against entrenched private interests. This is the opposite of simply removing all requirements and hoping markets would sort themselves out.

But Almonte understood something deeper. He could not quickly fix the fundamental constraints: constitutional restrictions, electricity prices and infrastructure gaps.

He could not make the Philippines competitive in manufacturing against Thailand and Vietnam.

So, he developed a different thesis: the Philippines could leapfrog from the agricultural stage to the post-industrial age. The country could not compete with China back then in labor-intensive manufacturing.

But the Philippines had something China and similar countries like Vietnam lacked: mass English fluency and a large, educated workforce comfortable with American business culture.

So, his team came up with a leapfrogging strategy that involved, among others, the nurturing of a business process outsourcing sector.

In 1992, the country’s first contact center was established. In 1995, the Philippine Economic Zone Authority was instituted. In 2000, the outsourcing industry contributed 0.075 percent of GDP. President Arroyo gave it a bigger push. Then it exploded.

Today, 1.5 million Filipinos work in business process outsourcing (BPO) and the industry contributes over seven percent of GDP. The leapfrog had worked. The Philippines had found a sector where it led the world.

A similar logic guided the shaping of the Philippines’ modern tax incentives regime.

When we were crafting the system under CREATE and later under the CREATE MORE Act, one of the most contentious debates was the export sales threshold required to qualify for exporter privileges.

The Department of Finance wanted a threshold of 90 percent. I bargained for 70 percent, partly because compromise was necessary, but mostly because my broader aim was to erode the artificial distinction between export-oriented and domestic-oriented enterprises.

What should matter is not the destination of sales. What should matter is the gross value added that an investor actually brings into the economy.

The compromise eventually settled on locational differentiation. The farther an investor is located from Metro Manila, the longer the incentives, because marginal investments outside the capital move the needle more.

We also adopted prioritization by industry tiers. The higher the tier, the more important the sector is to national development and the stronger the incentive package.

Yet even this remains incomplete.

The ideal system is one where an investor simply arrives with the capital and the technology and a competent government functionary handles the entire sequence of permits and approvals, then presents a single package of tax and nontax incentives tailored to the investor’s sector and potential value added.

A system that rewards contribution rather than compliance with arbitrary thresholds would be a decisive step toward genuine competitiveness.

The Path to redemption

The constraints that have strangled Philippine development are not mysterious. They are policy choices that can be reversed by different choices.

The longstanding economic consensus is straightforward liberalization. Remove the restrictions. Let markets work. Attract investment through competitive costs, including competitive wages.

I dissent from this view on one fundamental point: wages.

The Philippine domestic market is weak because Filipino wages are weak. The economy relies on remittances to fuel demand that domestic wages cannot generate. This is not a development model. It is a dependency model.

High wages are not merely a cost. They are a source of demand. Henry Ford understood this a century ago when he paid workers enough to buy the cars they built.

Historians debate whether Ford’s motivation was demand creation or reducing costly turnover, but the effect on purchasing power was real regardless of intent.

The counterargument is obvious: high wages deter investment. But the Philippines has already lost the race to the bottom and the reason is not wages. It is electricity.

Vietnamese wages are lower than Philippine wages. But Vietnamese electricity is also half the price.

When I advised some national campaigns in 2022, I tried to goad candidates to push for a P1,000 minimum wage, contingent on reducing power cost to P7 per kWh.

The logic was simple: businesses remain competitive because their electricity bills fall even as their wage bills rise. Workers gain savings for housing (where upwards of 90 percent of household wealth in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries comes from), health, retirement. No candidate took up the challenge.

Is P7 per kWh achievable? The generation costs suggest so. Rooftop solar now costs P2.50 per kWh without financing. Utility-scale solar has been contracted at as low as P2.99 per kWh.

Wind power is being bid at ₱3.50 per kWh. These are already below the target.

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis estimates that renewables could cut wholesale power prices by 30 percent.

The obstacles are not technological. They are institutional.

Legacy take-or-pay contracts with IPPs cannot simply be wished away. Transmission infrastructure requires massive investment. The transition would take years, not months. But the direction is clear: renewable power can be cheap.

As my own contribution, I have started and gifted with an endowment, the Albay Institute for Artificial Intelligence (AI).

The institute has a threefold mission: to democratize AI tools so ordinary Filipinos can use them, to generate products that solve local problems and to codify what we learn into policies adaptable elsewhere.

My hope is that, by iterating small steps across the regions, we can come across the solutions, perhaps serendipitously, as often happens in the scientific process.

The choice

For most countries that graduated from developing to developed, the pattern was the same.

There was a core of subministerial technocrats who stayed in the permanent state, accumulated expertise across administrations and understood how to design long-horizon industrial strategy.

Their ideas became national policy when the President was willing to spend political capital to shield them from resistance and push reforms through entrenched interests.

The Almonte team showed that even within Philippine constraints, deliberate strategy can create success. The BPO industry is a proof of concept. The task now is to extend that proof beyond a single sector.

But redemption requires honesty about where we are and the willingness to make hard choices.

For instance, we have been backsliding in English, the very asset that powered the BPO industry. Our ranking fell from 22nd to 28th in the 2025 English Proficiency Index. But can even the most hardened Filipinista honestly say we have become better at Filipino as a result? We have not traded one fluency for another. We have simply become less fluent.

The Philippine Institute for Development Studies documents what teachers already know: there is, on the ground, practically a “no fail policy” in our schools. This is not a path to high-wage employment.

On corruption, the lesson is institutions. The Central Bank used to be something of a slush fund, a tool for behest loans to favored cronies. Today, it is among the most professional central banks in the region.

But that transformation did not happen by accident. The Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas had to be reformed, financially remade through the New Central Bank Act, its balance sheet cleaned up, its independence institutionalized, its staff professionalized over decades.

The patience required for that kind of institution-building is the patience we lack elsewhere.

The right to do business in the Philippines should be open to anyone in the world. The condition should be simple: pay Filipino labor well.

But openness without competence is just another form of dependence. We must rebuild what we have allowed to erode: the English fluency, the technical skills, the institutional credibility that make high wages possible.

This requires hard choices: standards that refuse to promote students who have not learned, reforms that promote officials who can perform, and institution-building stamina measured in decades rather than election cycles.

Jose Almonte is 94 years old, and his former undersecretaries and assistant secretaries are no longer young.

Amid the political noise, the task of long-term development is to find their successors and to give them the political support required for difficult choices.

We have stalled for 40 years. We cannot waste 40 more.

Joey Sarte Salceda was research director of various multinational institutions during the 1990s, before entering Congress in 1998. He later became co-Chair of the UN Green Climate Fund. He is currently Chair of the Institute for Risk and Strategic Studies, Inc., a policy think-tank.

A welcome approach in Congress