Slain, missing activists join Bantayog heroes

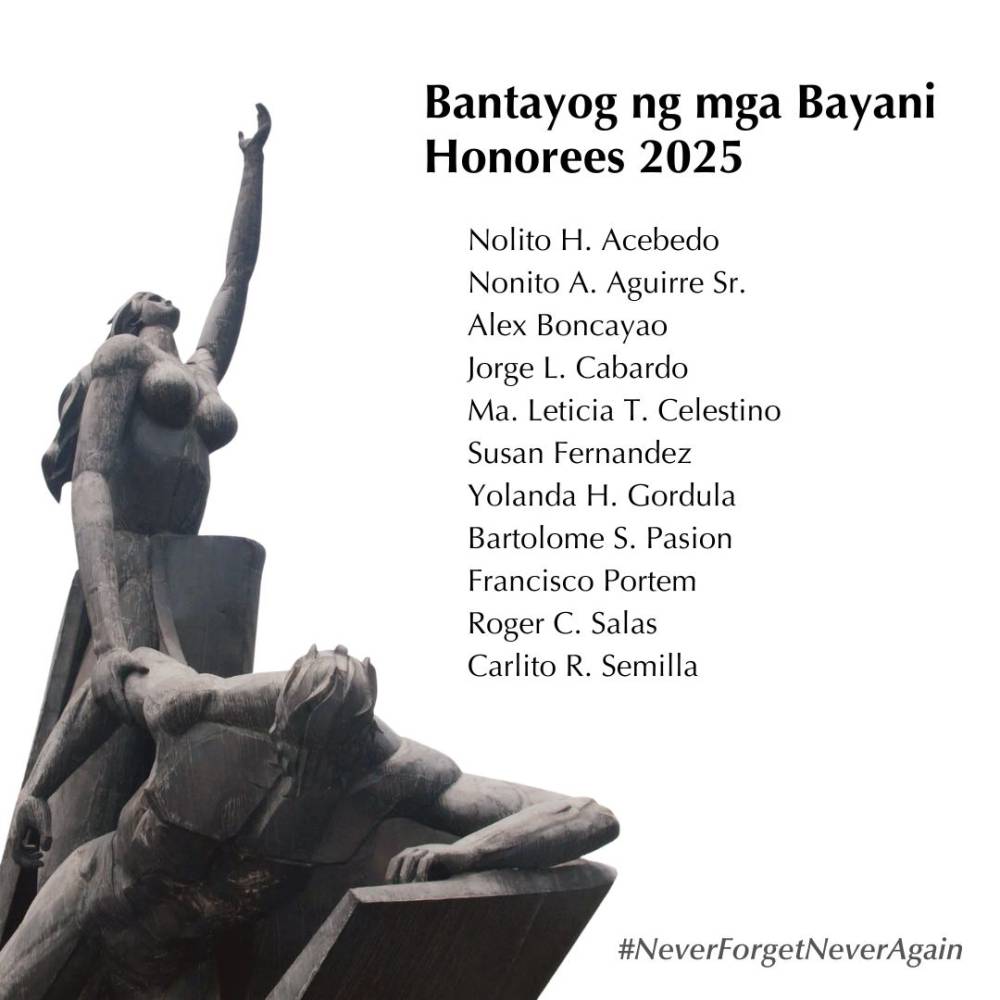

Nolito Acebedo. Jorge Cabardo. Francisco Portem. Carlito Semilla. Alexander Boncayao. Maria Leticia Celestino. Roger Salas. Nonito Aguirre Sr. Susan Fernandez-Magno. Yolanda Gordula. Bartolome Pasion.

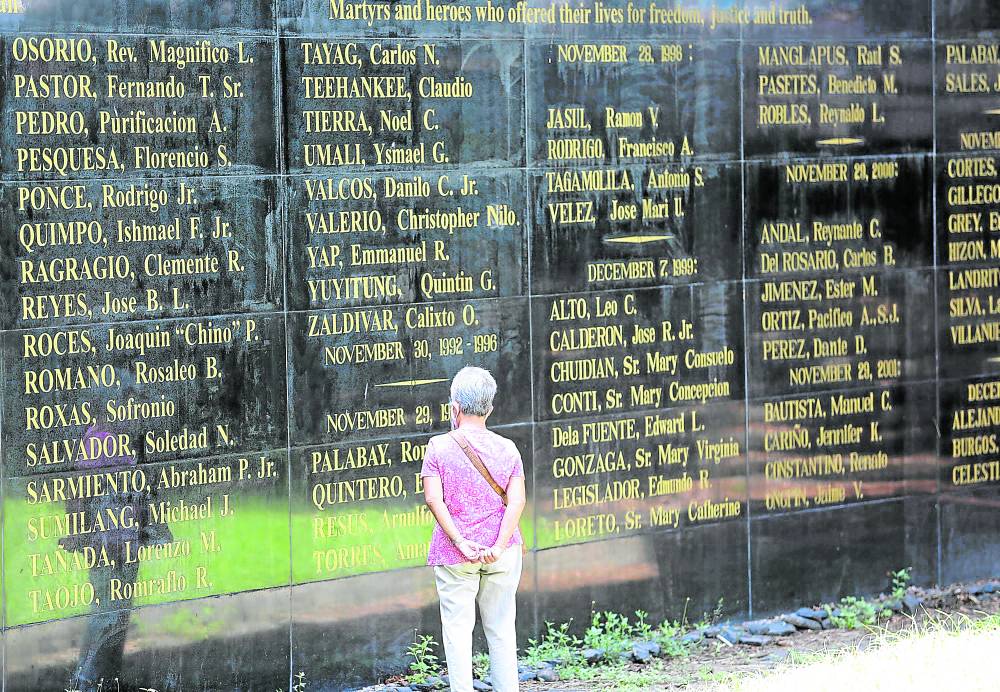

Their names were etched on Bantayog ng mga Bayani’s Wall of Remembrance in Quezon City on Sunday as the latest additions to the roster of 350 martyrs and heroes who chose a life of struggle against the regime of then strongman Ferdinand Marcos Sr., father of President Marcos Jr.

When the First Quarter Storm broke in early 1970, activist Acebedo was organizing rallies and propaganda campaigns, together with his older brother Roy. They were arrested in 1973 and six years later, Acebedo was killed in an ambush.

Bantayog cited him “for his involvement in the student political activism movement in Metro Manila … where he organized protest actions calling for academic reform and taking positions about social issues such as rising oil prices, rampant government corruption and calling for the release of political prisoners.”

Cabardo, a student leader and member of the Kabataang Makabayan (KM) national council, was among those arrested and charged by the military following raids in Metro Manila before Marcos Sr. declared martial law on Sept. 21, 1972. After posting bail, he settled in the Visayas, where he continued to organize for the movement. But he was later captured again with his wife Rosario.

The couple ended up at a military camp in Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City, joining high-profile prisoners Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., Jose Diokno, Eugenio Lopez Jr. and Serge Osmeña III. Then he made a daring escape, even helping Lopez and Osmeña break out of the maximum-security prison as documented in the 1995 movie “Eskapo.” He died of natural causes at age 38.

Victim of Red-tagging

Cabardo was recognized for “relentlessly opposing the dictatorship despite several incarcerations, withstanding beatings and abuse; and for leading and speaking in protest marches and rallies despite dispersal operations and threats to his life.”

Portem, another KM activist, was among the students arrested on subversion charges in 1971. After he posted bail, Marcos suspended the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, prompting Portem to plunge into full-time political organizing.

From Manila, he was sent to Isabela and his home province of Camarines Sur, where the military later tagged him as a New People’s Army (NPA) leader and launched a manhunt against him with a “wanted-dead-or-alive status.” The military eventually captured him and his family never saw him again or his body.

Bantayog paid homage to Portem for “leading protests against substandard school facilities, tuition increases and loss of academic freedom, and other national issues such as the worsening corruption of the Marcos regime, and Philippine involvement in the US war in Vietnam.”

Semilla, a KM leader in Davao City, quit college and left his home after it was raided by soldiers. He lived with farming communities in Davao del Norte and Davao de Oro to continue the struggle against agribusiness companies taking over swathes of land.

But one day in August 1974, he and two others were brutally hacked to death by militia men while visiting a farmer’s house in Davao de Oro.

Semilla was honored “for organizing farmers by showing them their exploitative situation in the hands of big agribusiness plantations in control of large tracts of land and being at the forefront of raising farmers’ political awareness by organizing various cooperative activities to improve their living conditions.”

Killed in military raid

A factory worker in Manila, Boncayao joined the underground movement with farming communities in Nueva Ecija. He was killed in a military raid when he was 36 years old.

The NPA’s hit squad, the Alex Boncayao Brigade, was named after him, even though he did not join the guerrilla movement.

Boncayao was recognized for “assuming exemplary leadership in the labor union movement during perilous times, particularly with his involvement with the Alyansa ng mga Manggagawa para sa Tunay na Unyon in Solid Mills, the Bukluran ng Manggagawang Pilipino, a workers’ political group engaged in antidictatorship work, and the Progressive Workers’ Union.”

Celestino, a textile worker from Aklan, found herself organizing unions when she traveled to Manila to seek better job opportunities. At 23, she was killed in a gunfire during a labor strike in a Valenzuela City factory.

“For fighting for the Filipino workers’ welfare and rights even under threat of dismissal by the factory owners and violence by goons, scabs and the fascist military; and for giving up her young life in defense of a workers’ barricade when she was fatally shot at the factory gates,” Bantayog said in its citation.

Salas, on the other hand, championed the rights of Filipino employees against their American employers’ discriminatory policies. He later became a full-time resistance organizer in Mexico and San Luis towns in Pampanga until he was captured by the military and later killed.

Bantayog honored him “for daring to join a workers’ union inside the then US Clark Air Base, becoming a shop steward, and helping co-employees voice out grievances and offer reforms; and for promoting their rights as workers and fighting for their security of tenure, retirement pay and other benefits.”

Beyond the classroom

Aguirre and Magno, both teachers, brought their advocacies outside the classroom to join the struggle against the Marcos regime.

Aguirre put up an alternative school with indigenous communities in the mountains of Aklan and Capiz provinces. He died in an accident.

A sociology student, Magno was a staunch women’s advocate and singer-composer who performed for political rallies and symposiums during martial law. Later known as the “nightingale of the Philippine protest movement,” she died of natural causes at 52.

Gordula volunteered for the nongovernment organization Friends of Coconut Farmers and Workers (FCFW) that helped organize coconut farmers in southern Luzon against the coconut levy. As an active member of FCFW, she later joined a medical support group before she went missing in 1983.

Pasion was a guerrilla fighter of the Hukbong Bayan Laban sa Hapon. After World War II, he fought the dictatorship by joining the Kilusan para sa Karapatan at Kalayaan ng Bayan and forming the Agumang Capampangan in South Cotabato.

He also launched an agrarian movement that grew vegetables and fruits on lahar-damaged land in Pampanga, benefiting some 7,000 individuals.