The short film as the voice of the new generation

I’ve been teaching at the film department of De La Salle – College of St. Benilde since 2017 and in my eight years of teaching, I’ve discovered a whole new appreciation for the short film. In the past five years, my work as a screenwriter and critic has given me the honor to be invited as a jury for school-led film festivals or thesis defense panels.

I’ve judged films in Benilde, Far Eastern University, and International School Manila. I’ve also been invited to be part of the selection committee of a few local festivals both in Manila and in the regions and can safely say I’ve seen over 600 short films in the past three years. At one of the writing workshops I was facilitating, sponsored by the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP), FDCP chair Jose Javier Reyes said in his opening remarks that the short film is harder to do than a full-length feature because you need to be able to tell a complete story in under 20 minutes. He also mentioned that it is in the short films where we can really see the most interesting stories made by Filipino filmmakers today.

After all, short films are self-produced personal projects by filmmakers, both by young directors and screenwriters trying to make a mark in the cinematic landscape and by professionals and experienced storytellers who want to produce and tell stories without studio interference. It’s in this medium that artists can experiment, try out new narratives, and break boundaries. These are works that more often than not have no real avenue to generate profit. The short film is not measured by its box office. This is expression in its purest sense.

For a film teacher, December is a busy time for short films. It’s the end of a semester (or trimester for other schools) and schools are holding their thesis defense for their film programs. For Benilde Film, our defense runs for four days, from Dec. 2 to 5, with 31 projects presenting their movies to a panel of industry professionals, film critics, and film scholars. They will defend their choices in a room filled with their peers and the lower batch who have worked as crews on their productions. It’s an exciting time with some students skipping class to attend the screening.

While the students are being judged and graded as a final requirement before graduation, the films they’ve worked on all term/semester will also be their calling card for when they set out to join the industry after they graduate. Oftentimes, they send their films out to local and international festivals. On a personal note, I get so excited when I see a Benilde thesis film make it to Cinemalaya or Gawad Alternatibo or any other local festival. A testimony of all the hard work they’ve put into their craft. I’m sure it’s the same for every film teacher in the country.

Short but impactful

I feel that this year’s Cinemalaya shorts, both in Set A and Set B, were a very strong set of films. The rawness of “Kung Tugnaw ang Kaidalman Sang Lawod” by Seth Andrew Blanca was a riveting exploration of the dark side of a seaman’s life, a peak into loneliness and exploitation. The visual language of that piece was so strong despite its bare bones production.

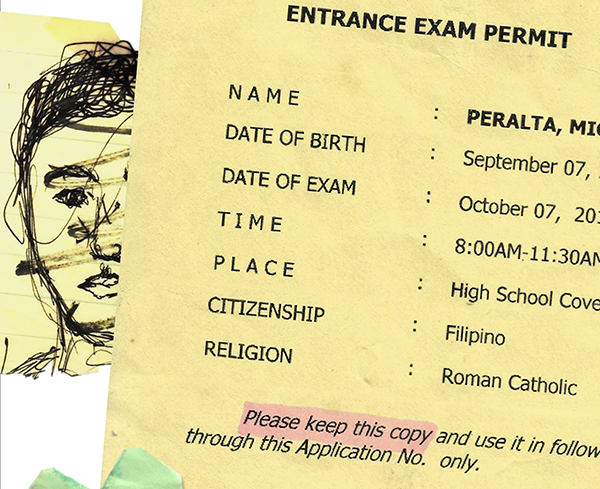

“Please Keep This Copy” by Miguel Lorenzo Peralta and “Kay Basta ang Karabo Yay Bagay Ibat Ha Langit” by Maria Estela Paiso uses a dynamic cinematic style that elevates their documentary and docufiction films to staggering effect. It’s cerebral and packs a hard punch and still manages to be visually arresting.

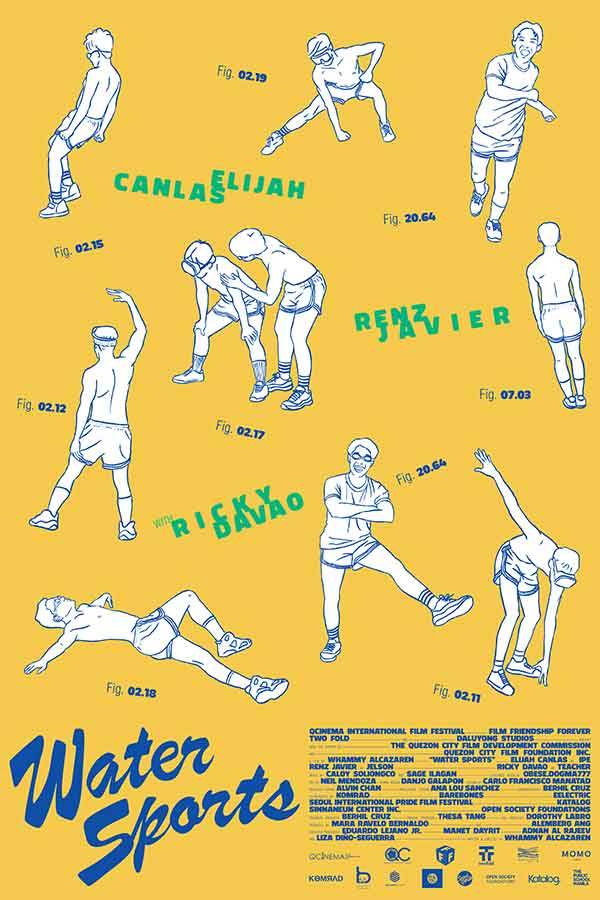

Whammy Alcazaren’s “Water Sports” and Arvin Belarmino’s “Radikals” shows the seasoned filmmaking veterans’ full use of the medium to bring us into another world in less than 20 minutes. “The Next 24 Hours” of Carl Joseph Papa uses animation to both soften and also amplify the dark subject matter of sexual assault while humor and pathos go hand-in-hand in Elian Idioma’s “I’m Best Left Inside My Head” and the whimsical “Ascension from the Office Cubicle” by Hannah Silvestre, a thesis film from Benilde.

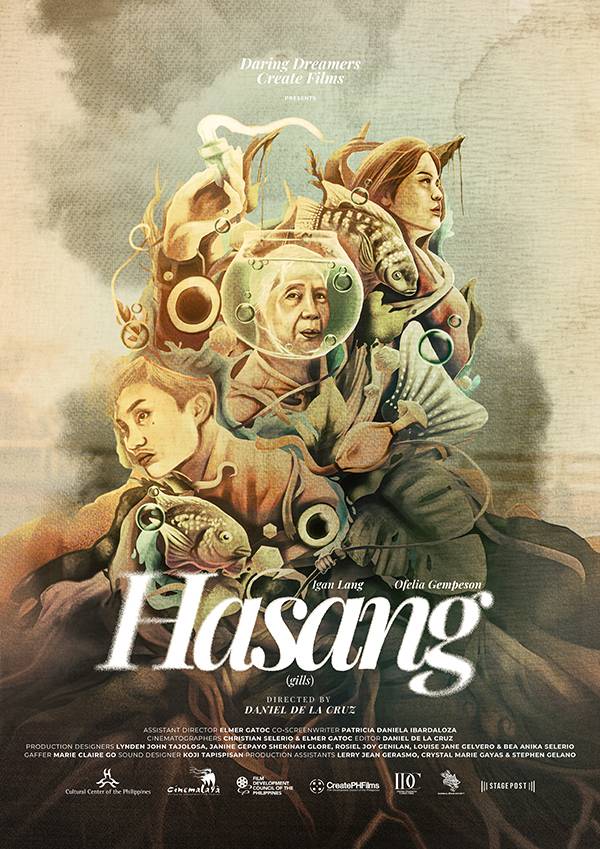

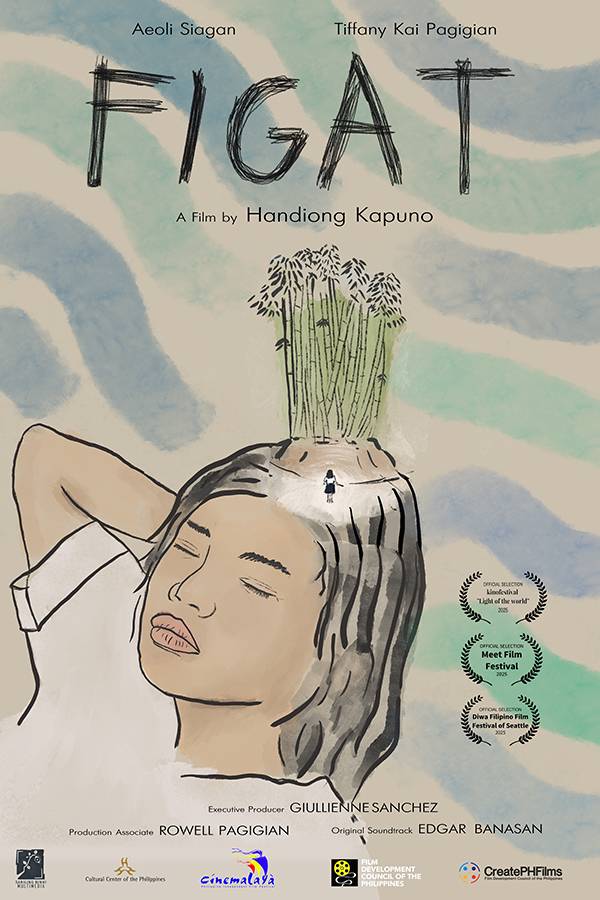

But of this batch of Cinemalaya shorts, “Figat” by Handiong Kapuno and “Hasang” by Daniel Dela Cruz are my standout favorites. Both films, made in the regions, tells a simple story of its characters but manages to subtly make powerful jabs at a destructive, unforgiving system. For “Figat,” it’s about how the government has not done enough for the Kalinga people while “Hasang” makes a pointed commentary about the destruction of our environment.

It’s such a strong batch of films with a number of them being far more engaging and hard-hitting than their full-length counterparts.

What also makes them so delightful is that these films are so playful with their style, subject matter, and approach to filmmaking. We don’t get to see this in mainstream cinema and, sometimes, even in our indie movies. These films and all the other short films that can be seen in the different local festivals around the country show how talented the Filipino filmmaker truly is. We need more of these stories and cinematic styles to bleed into our full-length works.

Voice of a new generation

From the hundreds of short films I get to see in my various roles in the industry, I’m seeing a whole lot of stories about our young artist’s hopes and dreams. In the past two years, I’ve seen dozens of films and documentary shorts about our fishermen and their plight. I’ve seen over 50 sapphic films, which led me to write a previous article about the lack of sapphic films in our cinematic landscape (though “Open Endings” answered that call in this year’s Cinemalaya full-length category but we certainly need more). Stories that explore mental health issues are also prevalent, a topic that’s on the minds of many young people out there.

The full-length films we get to see in the cinemas and on streaming sites are studio-led, which means there’s a committee behind them using available metrics and standards to determine what stories they think people will come to the cinema for among the many things they could watch on a streaming platform. Diluted by a committee and driven to ensure profit so they can get a return investment, the film can be watered down by the fear that people won’t watch something new. It’s why the usual social media comment you see about Filipino films is “we’ve seen it before. It’s nothing new.”

But there are films out there that tell a different story from the one people may think is always being told. You want to see how films can capture the true nature of our nation? And not just in Manila but in the different regions of our country? I urge you all to take some time to watch more short films. Catch them in the festivals next year: Cinemalaya, QCinema, CinePanalo, Gawad Alternatibo, Sine Kabataan, and a whole lot of others. They are all just waiting for you.