Respect, resilience, and a radical change in mindset

Climate-resilient food has been part of the zeitgeist in recent years, especially within the environmental and food security sectors. Food security has been another buzzword that has also been highlighted. In fact, the Philippines is blessed with so many natural resources, with natural harbors such as Manila Bay and Pasig River, which also act as a means of transportation and brim with development and tourism potential.

While cities such as Sydney had to create their picturesque Sydney Harbour, Manila Bay is a cheap fairground surrounded by unsightly structures. The Pasig River meanwhile is surrounded by billboards full of trash and scenes of squalor, unlike the similar Chao Phraya in Bangkok.

In the same way we have misused our natural bodies of water, the country has also sidelined the production of endemic climate-resilient foods. A report from The Food and Agriculture Organization specifies that climate-resilient crops such as cassava, cowpeas, maize, sweet potatoes, and yams—all of which are part of local diets and agriculture—are not eaten or consumed regularly.

A mindset of abundance

In my experience working in communities, I often hear people say “gulay lang kami pag walang makain.” (“We only eat vegetables when we have nothing to eat”) That one word—“lang”—signals a lack of, whereas having something more than vegetables denotes abundance.

What plagues the Philippines is malnutrition, not necessarily the lack of food, but the lack of correct nutrition from proper foods. Instant and processed food is killing Filipinos via non-communicable diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension. And the food that we are naturally blessed with—such as the “dahon” of plants like kamote, sayote, and malunggay—is strangely hard to find in large quantities, when hundreds of kilos are needed to feed many Filipinos, as they are mostly planted for personal consumption.

Instead, upland vegetables such as carrots, cabbage, and cauliflower are mass-produced and flood markets across the country, even to the point of wastage. Native vegetables, on the other hand, are not grown in mass quantities since they are not viewed as profitable. And yet, those who have their own vegetables planted in the backyard are the luckiest and have a supply that meets their needs.

Many organizations sell these overproduced vegetables in Manila, much to the delight of city dwellers, but even this does not solve the problem of overproduction, waste, and loss. What is glaringly obvious is that we do have enough food for the people, despite being able to grow it in our lands.

What’s more, the problem is that it is not reaching enough people—and it is not reaching them at a fair price.

Creating a demand

The next issue we face when it comes to the availability of food is creating a demand for locally available healthy food. The Philippines is home to hundreds of varieties of beans, yet they are hardly found in our daily cuisine. India feeds thousands of people on a daily basis using the same kinds of beans and grains that are found in the Philippines. Cowpea, mung bean, and millet all grow in our land and are naturally climate-resilient. But due to the lack of demand, they are not planted as abundantly as other crops.

The Filipino preference for food has shifted to instant food, salty, sweet, sugary, and packaged. A sack of sweet potatoes doesn’t light up people’s eyes in the same way as a red hot dog does. Many fine dining establishments make use of local ingredients to highlight the local fare with great effort in order to elevate the local produce; however, this is not enough to create a big demand for the “dahons.”

Plants such as pansit-pansitan (Peperomia pellucida), which is essentially a weed found on most street corners, make an appearance as a garnish in fine dining restaurants when it is actually a medicinal plant that helps lower blood sugar. Talbos ng kamote is a good source of antioxidants, perfect for a warm salad—or even blanched kangkong, dressed with a vinaigrette instead of a salad of lettuce. Meanwhile, raw sayote and singkamas serve as crunchy toppings that can rival the usual grated carrots.

An abundance of junk food over an abundance of healthy food

In my experience of teaching healthy cooking around the country, most Filipinos already know the benefits of our local food and that vegetables are key to a healthy life.

But what plagues us is the abundance of choice for instant, fast, and junk food. The convenience of packaged food that never goes bad is also a big reason many opt not to cook anymore.

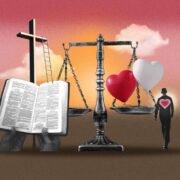

What is also sorely lacking is discipline. The discipline to throw trash in the proper places. The discipline to invest in our health by taking time to cook, prepare a meal, and chew slowly. The discipline to eat mindfully and consume more local fruits and vegetables.

In the same way we build immunity by eating healthy and living active lives, treating our natural resources with respect ensures fewer floods, less erosion, and less pollution. The way we treat our bodies is how we should treat the environment—with mindfulness and respect.