Not losing hope on Philippine cinema

For decades, Philippine cinema has relied on a traditional, cinema-centric model, and if box-office returns remain the sole barometer of its health, most industry insiders would agree that it’s hanging by a thread.

It all happened slowly and then all at once. After what was touted as the “Second Golden Age” of Philippine cinema in the early 1980s, the industry faced a growing, evolving set of challenges that triggered a steady decline in film production and theater attendance: higher taxes and escalating ticket prices, intense competition from Hollywood, and rampant piracy.

Then came the rise of digital media in the 2010s. The inevitable transition from cinema-going to streaming was something many had already predicted. But by 2017, with major players like Netflix quickly gaining footing, the change had become impossible to ignore.

Dramatic change

At first glance, everything seemed fine. While it was already apparent that the maximum earning potential for movies was most achievable during seasonal, protected runs like the Metro Manila Film Festival (MMFF), the year-round market was still able to deliver box-office blockbusters like “My Ex and Whys” and even surprise indie hits like “Kita Kita.”

For a while, the industry thought it still had enough time to adapt, but then the pandemic struck, fast-tracking the adoption of streaming. Today, with ticket prices almost as high as the average minimum wage and viewers more or less settled into their viewing habits—binge-watching K-drama and foreign films at home or on the go—it has become harder than ever to bring people back to cinemas.

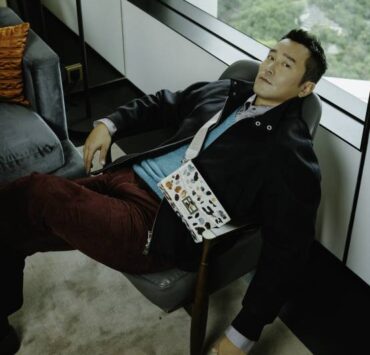

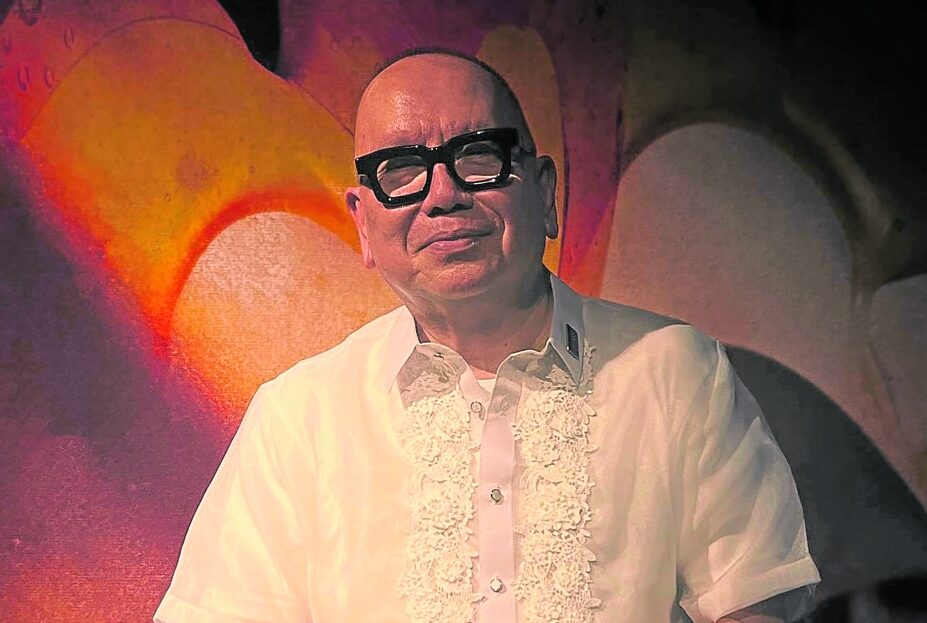

“The shift in the habits of the audiences for the consumption of entertainment due to almost three years of confinement brought by the pandemic resulted in the hastening of the decrease in viewing movies in cinemas,” Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP) chair Jose Javier Reyes tells Lifestyle Inquirer.

“It was on its way there as early as 2017, but was pushed further when people learned to enjoy their content in the comfort of their homes through streaming or internet platforms,” he adds.

A collaborative ecosystem

It’s clear that the business model of movie production, distribution, and exhibition has changed dramatically, more so after the pandemic. Reyes stresses that only by acknowledging these challenges, addressing the problems, and innovating to meet the new demands can the industry hope to stay afloat.

For the most part, this meant broadening the definition of cinema, not as something strictly confined to the theaters, but as an experience that could reach audiences anywhere. It also meant recognizing streaming platforms as more than just an alternative, and perhaps even the primary way films are showcased.

As a result, we have seen more and more traditional film outfits—such as Star Cinema, Viva Films, Regal Entertainment, and GMA Pictures—collaborating and forming partnerships with streaming platforms like Netflix, Viu, and Prime Video. Some have even launched their own streaming services.

“There’s a need to coexist with platforms and design acceptable business plans and strategies to accommodate the eventual migration of content from screen to streaming, or the development and creation of straight-to-streaming materials,” Reyes says.

Aside from this increasingly collaborative ecosystem, Reyes also notes the rise of short-form entertainment, such as vertical series, which is one prominent emerging format that “delivers narratives in four- to five-minute installments unfolding over a series of episodes and developing its own storytelling style and use of audiovisual elements.” This is something the likes of GMA, Viva, Puregold, Cignal, and Cornerstone Entertainment have already caught up on.

Tapping the diaspora

Another key and successful innovation in the industry, Reyes says, is the strategic focus on globalization.

More than exploring new formats or media, Reyes points out that there’s a need for a shift in mindset—from local to global—not only in terms of storylines, but also in production and distribution. Initiatives such as the FDCP’s International Co-Production Fund and the QCinema Film Market support and help encourage this mindset.

“Producers must recognize that as long as their storylines cater only to local or parochial audiences, they risk extinction. Globalization, however, offers opportunities through more creative distribution methods and the advantages of foreign co-productions,” Reyes says.

There have also been efforts, most notably by Star Cinema, to transform the local market into a “migratory” one by tapping the Filipino diaspora. After all, an estimated 12 million Filipinos live overseas, representing a significant and largely untapped audience.

Movies like “Hello, Love, Again,” “Rewind,” and, most recently, “Meet, Greet, Bye” have benefited greatly from this strategy. The box-office success of these films, achieved through simultaneous international releases, validates this model and shows that local films can now become a global Filipino product.

“Producers are learning the value of the international market. The success of movies like ‘Rewind’ and ‘Hello, Love, Again’ came about because studios tapped into the Filipino diaspora, acknowledging the buying power of Filipinos abroad and their eagerness to watch local films they miss,” Reyes says.

“Simultaneous openings in foreign cities and targeting diaspora communities are only the first step,” he stresses. “What is crucial is that, through these experiences, we can also entice foreign audiences to watch our films.”

Unrelenting drive for storytelling

Despite all the challenges the local industry has to wrestle with, one thing remains unchanged: the talent of Filipino filmmakers and their unrelenting drive to continue telling our stories.

Antoinette Jadaone’s “Sunshine” won the Crystal Bear Award for Best Film at the 2025 Berlin International Film Festival and reportedly earned P47 million at the local box office—an admirable feat for an R-16 film tackling a still-taboo topic like abortion. Similarly, TBA Studios dared to take risks with historical narratives, releasing Jerrold Tarog’s “Quezon” at a time when even familiar mainstream films struggled to perform.

Documentary filmmaking has also made waves. Baby Ruth Villarama’s “Food Delivery: Fresh from the West Philippine Sea” won the Tides of Change Award at the Doc Edge Awards 2025 in New Zealand. Meanwhile, Lav Diaz’s “Magellan”—the Philippines’ official entry to the 2026 Oscars—is being touted by industry observers as a potentially strong contender.

Local film festivals continue to provide crucial platforms for filmmakers. The 2025 Cinemalaya Festival generated P13.4 million at the box office—a 131 percent increase from the previous year’s run—despite funding constraints. Festivals such as Sinag Maynila, QCinema, and CinePanalo continue to help filmmakers bring their visions to life, while niche events like Cinesilip, the erotica film festival organized by VMX, have been surprisingly well-received.

So while local cinema stands on shaky ground and its future remains uncertain, it nevertheless—and must—persists.

“We never give up hope,” Reyes says. “Challenges are meant to teach us lessons and provide us directions. We only sink deeper if we insist on our version of the past, and do not confront the situation of the here and now.”