Release the SALN!: Reporters finally get hold of key document

For a long time, journalists have been practically denied copies of statements of assets, liabilities and net worth (SALNs) of high-ranking government officials that reflect their wealth while in office for public scrutiny.

Former Ombudsman Samuel Martires set tough barriers in 2020 before anyone, including journalists, could obtain a copy of the SALNs purportedly to stop the document from being used as a weapon against politicians and other public officials.

But after his successor, former Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin Remulla, took the Office of the Ombudsman in October, he lifted those restrictions, allowing members of the press to obtain SALNs with certain requirements that are less stringent.

Remulla’s order took effect on Nov. 17, after his memo was published by the Official Gazette. Among the first batch of media companies to request copies was the Inquirer.

This reporter filed requests for the SALNs of both President Marcos and Vice President Sara Duterte on Nov. 18 (Tuesday), the day after the Ombudsman opened its doors to requests.

The Ombudsman’s Public Assistance Bureau manages all requests for SALNs from the press and the general public who want information about the state of wealth of certain public officers during their time in office.

‘Do’s and don’ts’

A staff member of the Ombudsman’s media affairs bureau informed the Inquirer about the “do’s and the don’ts” in handling the document, including how much information to share with other media outlets.

This reporter anticipated a long line of journalists lining up to submit requests for SALNs, but the queue was surprisingly short. Journalists from the Philippine Star, Manila Bulletin and Rappler submitted their requests later in the afternoon.

A person who requests for a copy of a SALN fills out two forms for each official. In the case. The front page of the form contains personal information about the person requesting—full name, address, contact information, among other things; the back page contains the terms and conditions and signature.

This reporter was assisted by one designated in-charge referred by the Ombudsman’s media affairs bureau.

The acting public assistance bureau director, lawyer Rawnsle Lopez, administered the oath-taking of this reporter, which included a condition to send the published story that used the SALN to the Ombudsman’s office five days after the publication.

‘Unusual requirement’

The Ombudsman charges P20 per page of a SALN copy for its release.

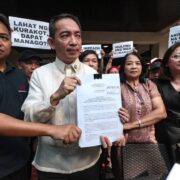

Peter Tabingo, a longtime reporter for the newspaper Malaya, also requested copies of the SALNs of the President, the Vice President and of former President Rodrigo Duterte.

“I waited for the new rules [of the Ombudsman] to come out before I filed my requests,” he told the Inquirer, noting that he had traveled from Pampanga to Quezon City just to make his SALN request. “It was expensive and tiring.”

He said he doesn’t mind submitting his own report to the Office of the Ombudsman, acknowledging that SALNs can be easily used to ruin one’s reputation.

“I understand how SALNs, when mishandled, can be used to smear a declarant’s reputation. Requiring submission of outputs can be a deterrent,” Tabingo pointed out.

This was similar to the sentiment of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), which described it as an “unusual requirement.”

“It’s an unusual requirement,” NUJP chair Jonathan de Santos told the Inquirer. “But if the premise is that the Ombudsman will use the stories as leads and tips for its own field investigation units, it might be a benign one.”

“It might also be a way to validate that the SALN request was for journalistic purposes,” he also said.