When ‘Ka Roger,’ ‘Ka Joma’ were a phone call, email away

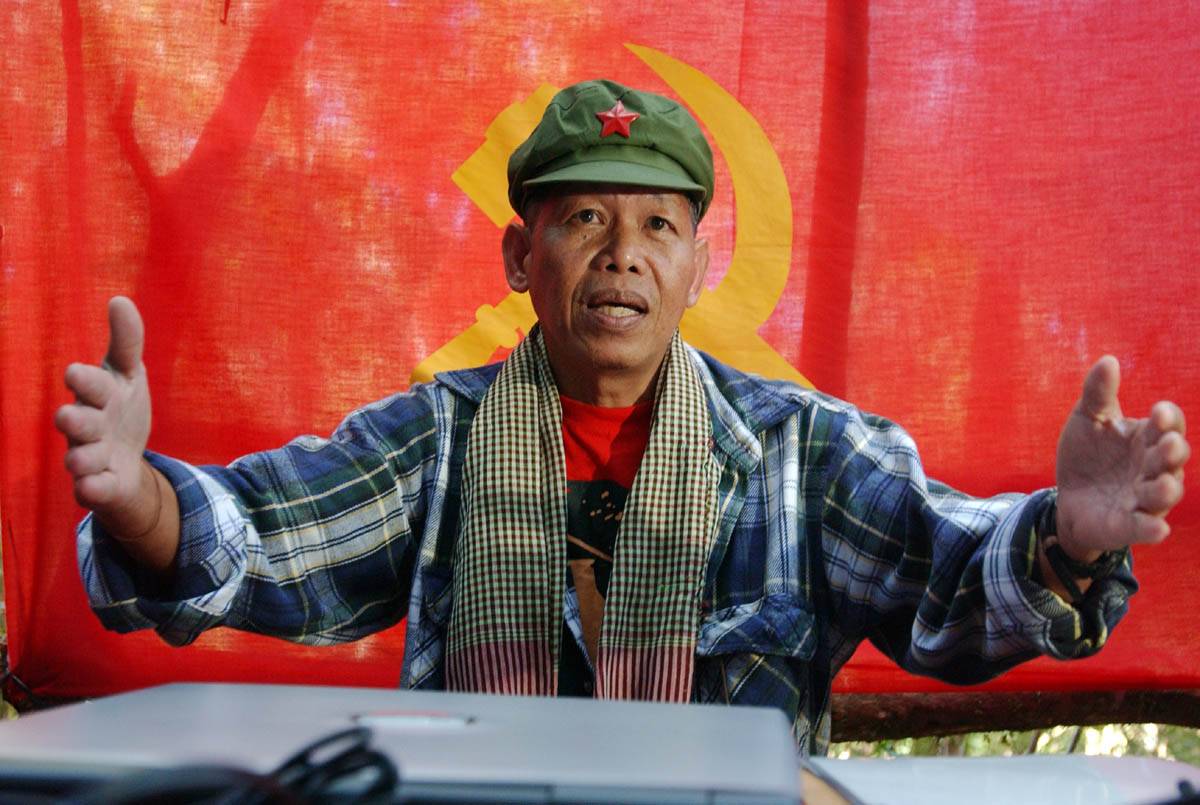

LUCENA CITY—Quezon had long been known as the bastion of the communist insurgency when I joined the Philippine Daily Inquirer in 1998 as its provincial correspondent. Mt. Banahaw, in particular, was known then as the lair of Gregorio “Ka Roger” Rosal, the New People’s Army (NPA) spokesperson who had become the face of communist rebels fighting in the countryside.

Naturally, every local journalist kept a close watch on developments on matters relating to insurgency—how many were killed, who was captured, and what each side was claiming.

Our daily grind depended on the latest reports from Camp Nakar in Lucena City, headquarters of the military’s Southern Luzon Command, as well as the Quezon provincial police. Radio reporters also frequently managed to interview Ka Roger through mobile phone calls.

The revolutionary movement’s own publications—“Ang Bayan” and the online statements of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP), NPA, and National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) through the Philippine Revolution Web Central—were also primary sources of information.

Like many provincial reporters, insurgency coverage became part of my daily routine. My mornings often began with a hot cup of coffee shared with military spokespersons or Army officers at Camp Nakar.

Firsthand info

Between sips, they would give me firsthand information, sometimes even exclusive details they allowed me to publish.

It was also my habit to call Ka Roger almost every morning to get his reactions to military statements or any incident involving the revolutionary movement the previous day. Often, he would ask me to read aloud the day’s issue of the Inquirer because his copy had yet to reach his hideout.

In return, I often secured scoops straight from the horse’s mouth. Our conversations usually ended with us comparing the breakfast we were having at that very moment—mostly boiled camote (sweet potato) for him and hot pandesal for me.

For our mutual safety, we even agreed on a “password” in case one of us lost his mobile phone. That password proved useful when Ka Roger’s phone was lost while he was fleeing a military raid.

At the time, the military was boasting that he had been seriously wounded and that troops were closing in on him. To disprove the claims, he called me—using my number written on a slip of paper that he kept in his wallet—and recited the “password” before issuing his statement.

Meeting in person

I met Ka Roger for the first time in 2001 in Mansalay, Oriental Mindoro, during the release of a soldier held captive by the NPA. When I introduced myself, he gave me a warm hug, saying, “At last, we meet in person. It’s my pleasure.”

That was the first and last time I ever set foot in an NPA camp. Although I received several invitations to witness events inside their lair, it had never been my practice to attend due to safety and security reasons.

Still, wanting to expand my sources beyond the local front, I searched for ways to reach the self-exiled communist leaders in Utrecht, the Netherlands.

It wasn’t difficult. I had been a student activist in Lucena City in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and I had already earned the trust of many local Red fighters by ensuring their side was always represented in my stories.

Trust

When I first reached out to CPP founder Jose Maria “Ka Joma” Sison via email, he immediately welcomed my initiative. He didn’t even ask for personal details, saying he already knew me from my reporting. He trusted me enough to give his personal email address for faster communication.

Whenever government or military officials issued statements about the insurgency or related topics, I would email Ka Joma for his reaction. Within minutes, he would send back his replies.

Through Ka Joma, I also established contact with his fellow Utrecht-based NDFP officials Fidel Agcaoili and Luis Jalandoni. I often chatted with them beyond formal questions and answers. In one humorous exchange, Ka Fidel and I began calling each other “primo” (cousin) after realizing we shared relatives in Lucban, Quezon.

Ka Joma and I also talked about personal matters, especially my family. But not once did he ask why I didn’t join the armed struggle, even though many of my contemporaries in the student movement had done so. I had a ready answer, but the moment never came.

Deep longing

Most of what I wrote based on my exchanges with Ka Joma involved updates on the often-stalled peace talks. He was unwavering in his revolutionary beliefs, but I also sensed a deep longing for peace.

Living in exile in the Netherlands since 1987, he sometimes spoke of home. In one conversation, he said he hoped to see relatives and friends again and savor Filipino food once peace was achieved.

“We’ll hold a family reunion. The first things I’ll eat are mangoes, coconuts, and bibingka (rice cake),” he said.

When Ka Roger died in 2011 and Ka Joma in 2022—both from heart complications—I mourned deeply. They were not just news sources; they had become friends, even comrades, in the human sense of the word.

My close ties with top communist leaders led some military personnel to label me an “NPA reporter.” But most senior officers whom I dealt with understood that I was simply doing my job—in a professional and fair manner—while navigating the delicate space between two opposing forces.