Gui-ob ni Tidoy: The living myth and legacy

ILOILO CITY—Deep in the mountain trails of Miagao town in Iloilo province, a striking block of rock rises from the thick, emerald-green forest. Its black-and-white limestone surface, with a chalky texture and gentle gradient of colors, stands in quiet contrast to the surrounding foliage.

Known as Gui-ob ni Tidoy, this natural monolith in Sitio Tulahong, Barangay Onop, has long served as a welcome rest stop for mountaineers and adventurers making their way up Miagao’s peaks. Its broad base offers cool shade, and its silent presence greets weary hikers at the heart of their climb.

For many mountaineers, the journey to Gui-ob ni Tidoy is as important as the destination. The trail winds down and passes through the misty-lush vegetation, and streams test both endurance and spirit. Upon reaching the rock, hikers often pause not only to catch their breath but also to appreciate the lulling breeze whistling a peaceful song as it passes through the rock.

For some, this rock is simply a resting place. For most adventurers, story hunters, and nature lovers, it’s a marker of perseverance. The rock is no ordinary waypoint but a place for pause, an anchor for the mountaineering community—a reminder that in the midst of challenge, there is always space to rest, reflect and reconnect with the land.

In recent years, Gui-ob ni Tidoy and its surrounding trails have grown in recognition, thanks to the efforts of Miagao’s tourism initiatives. The municipality’s emphasis on its tourism and cultural heritage has drawn adventurers from across Panay and even beyond, giving the site newfound visibility.

Yet, despite this, Gui-ob ni Tidoy retains its air of wonder, unpolluted by the exploits of tourism. Unlike commercialized destinations, it is untouched, as the journey must be reached by an adventurous spirit.

The myth

According to folklore, an unnamed maiden, burdened by a forbidden love, fled into the mountains to escape her fate. With her, she carried two heavy stones, each representing the weight of her grief and heartache. Her path was long and arduous, and along the way, she dropped one of the stones. This stone, it is said, became the formation we now call Gui-ob ni Tidoy.

Still carrying the second stone, she pressed further into the wilderness until she reached the summit of Mt. Napulak. There, her story came to an end in tragic sacrifice. Some versions say that she cast herself from the peak. Other versions say that she simply vanished, her body swallowed by the mountain itself. What remained, according to local belief, were her tears, which transformed into the rivers and streams that flow through Igbaras and Miagao, nourishing the land and its people to this day.

The very name “gui-ob” (or gihub) refers to the cracks and striations carved into the rock.

These fissures are more than geological details—they are metaphors for the fractures of the mythical maiden’s broken heart, scars that endure through time. To hear this story while standing before the rock is to see the landscape as more than scenery; it becomes a stage where human sorrow and natural wonder intertwine.

Yet, Gui-ob ni Tidoy does not carry its myth by itself. Its preservation rests in the hands of those who continue to live in its shadow. The second part of its name refers to Tidoy, whose real name was Pedro Nopat, the first man known to inhabit the area.

The Guardian

In local folklore, Tidoy is remembered as a medical practitioner, an “albularyo” (traditional healer) whose knowledge of herbal medicine made him a figure of both respect and mystique. Like many healers in local mythos, he was believed to have the ability to shape-shift into a lizard or a pig—a gift and a mystery that allowed him to thrive deep within the mountains. These local tales solidified Tidoy in local folklore of Barangay Onop.

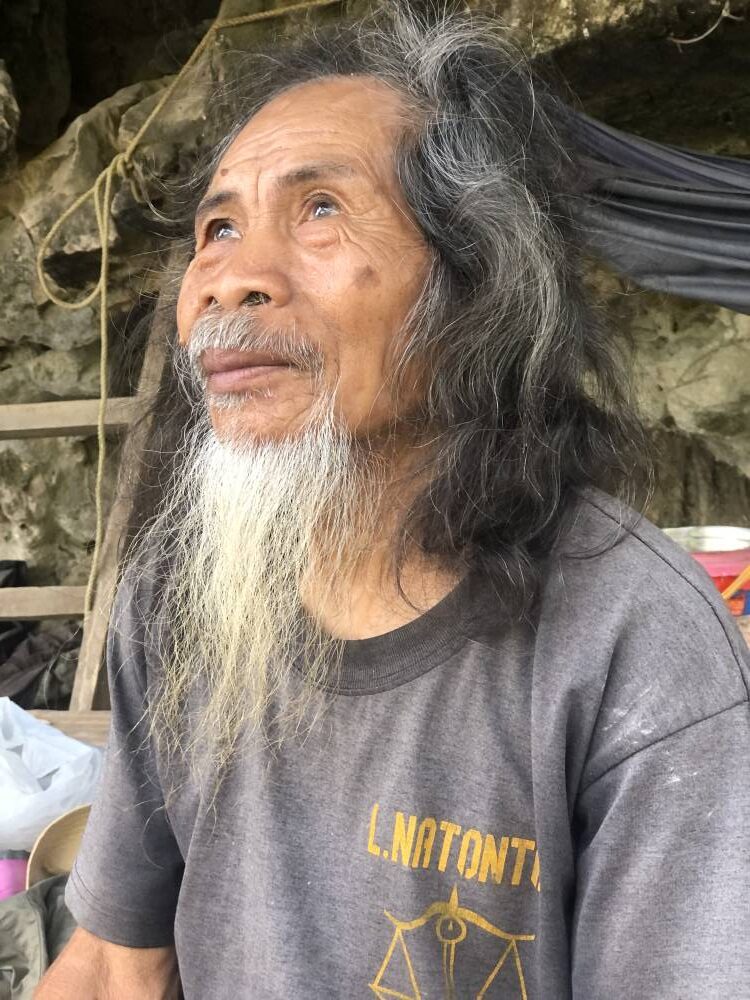

Today, the legacy of Tidoy lives on through his grandson, Simplicio “Tay Pisyong” Natonton, who, at 75 years old, remains the humble caretaker of Gui-ob. Known warmly by hikers and locals alike, Tay Pisyong continues the quiet guardianship that his family has upheld for generations.

Accompanied at times by members of his family, he maintains the surroundings of the rock, clears portions of the trail and watches over the visitors who pass by. He has become, in his own way, a living bridge between past and present, carrying the memory of his grandfather while also ensuring that the rock remains accessible and meaningful to the present generation.

When asked about his life in the mountains, he shared a simple sentiment: “Kung sa ako, nami gid doon sa lugar nga ginbuhian. Duro gid nga gakuon nga mangita ka lugar paubos pero ‘di gid ko maghalin digya. Daw diri guid ang lugar nga gina pangabuhi-an ko halin kang una (For me, I still love the place where I was born. Many tell me to find a place down the mountain, but I will never leave. This has been the place where I have lived since the beginning).”

For Tay Pisyong, Gui-ob ni Tidoy is not just a mere monolith. It is his home, heritage and history that tells an undying story beyond its cracks and crevices. It remembers the people, the myth and the guardianship that was passed down through generations. While the stone may just be a waypoint for any ordinary hiker, it remains a living monument, one that whispers the weight of its myth but also the warmth of human devotion.