Corruption with Philippine characteristics

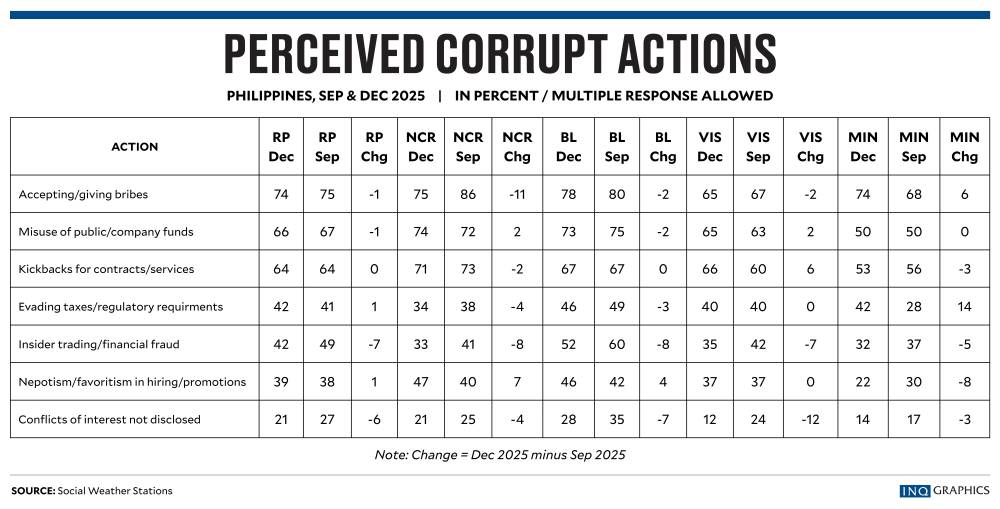

In September and December, Social Weather Stations (SWS) asked Filipino respondents some pointed, relevant questions. Which of these actions, it asked, in the private or public sector, do you consider corrupt? The top three won’t surprise you (but should); the answers that come next, will. Roughly speaking, three out of four Filipinos consider bribery to be corruption (but a quarter of the people don’t share the same view); two-thirds consider it corrupt to misuse public or corporate funds; about the same number consider kickbacks for contracts of services to be corrupt (but one-third thinks it’s OK). Here is where it gets even more interesting. Less than half think evading taxes or regulatory requirements, insider trading, or financial fraud is corrupt (more than half seem to think it’s OK), and more than two-thirds do not think that nepotism or favoritism in hiring or promotions is corrupt, while close to eight out of 10 Filipinos don’t see anything corrupt in not disclosing conflicts of interest. Our society seems to have a built-in moral elasticity, with more than enough approving of corruption to be willing accomplices.

SWS lumps together classes ABC (5.8 percent) into one; class D is the biggest at 87.4 percent (as of 2024); and class E (6.8 percent) is the poorest of the poor. Just as interesting is the change in the percentages for the best-off class ABC: financial fraud went down 15 points; insider trading or financial fraud went down 14 points; bribery as criminality went down 7 points, as did unreported conflicts of interest: a loosening, shall we say, of standards. You only find a double-digit slide downwards in Balance Luzon (-11 on bribery as corrupt) and the Visayas (-12 on unreported conflicts of interest). The opinions of class D on what is corrupt have hardly changed.

In an unrelated survey last November, WR Numero reported that 63 percent of respondents were very satisfied/satisfied with the performance of their representative; only 13 percent said they were very unsatisfied/unsatisfied; 18 percent were unsure, while 6 percent didn’t know who their congressman was. Two different surveys, true, but when you consider the House of Representatives has been one of the institutions under siege, a large majority thinking their reps are doing well suggests culpability only extends to outsiders.

One of my favorite stories of life as a columnist took place two decades ago. A Filipino migrant to the United States lectured me throughout a transpacific flight about the pervasiveness of corruption at home, only to take out a thick wad of bills as we were landing, counting them out into neat piles. Seeing my curiosity, he helpfully replied, “This is for Customs, this is for the police …” This explains why a congressman tried to keep provisions for unprogrammed funds in the current budget.

Recently, I discovered Rizal never wrote, “tal pueblo, tal gobierno” (as the people are, so is their government), however obviously truthful it sounds, to the extent it has become an apocryphal quote I’ve used in the past. Instead (and typically), he wrote, “An immoral government begets a demoralized people; an administration without conscience, rapacious, and servile citizens in town, bandits and thieves in the mountains! Like master, like slave. Like government, like country” (“A gobierno inmoral corresponde un pueblo desmoralizado, á administracion sin conciencia, ciudadanos rapaces y serviles en poblado, bandidos y ladrones en las montañas! Tal amo, tal esclavo. Tal gobierno, tal país.”) A necessary question moving forward, then, is: What exactly is the public angry about, and who exactly are the ones who are in trouble?

When leaders and followers alike conveniently make wide-sweeping accusations, it is actually a license to steal. This is why the popular phrase during the Arroyo era, “pare-pareho lang ‘yan!” remains so useful; it normalized official behavior while justifying the emerging consensus on the part of the middle class not to add to risk by engaging in regime change.

—————-

Editor’s note: Manuel L. Quezon III’s column, “The Long View,” will now appear twice a week, on Monday and Wednesday.

—————-

Email: mlquezon3@gmail.com; Twitter: @mlq3