How Filipinos cook, eat, and talk about food

Amparing, my mother, must have been Kapampangan. She lived in constant fear of running out of food. Not just some food. All food. “All animals on the table” was a phrase we uttered (often in awe and in gentle sarcasm) as we watched her maneuver through her table. Every animal, every part, every possible dish that could be coaxed from a market trip had to make it to the table. Nothing was too humble, nothing too strange. If it once sprouted, walked, swam, or flew, it deserved a place on mom’s spread.

Guests were never allowed to leave hungry—or worse, unsatisfied. Plates were refilled before they were empty. Seconds were assumed. Thirds encouraged. Leftovers were not excess; they were insurance or “backup.” It was the term I used to hear when dishes were set aside, just in case.

All our lives, my siblings and I watched her transform into the hostess with the mostest whenever she entertained.

Mom became overly hospitable—all mine to give, unnecessarily in panic mode, kinakabahan baka magkulang, and always a little exaggerated. It was just how she was.

Aha! Makurilyu!

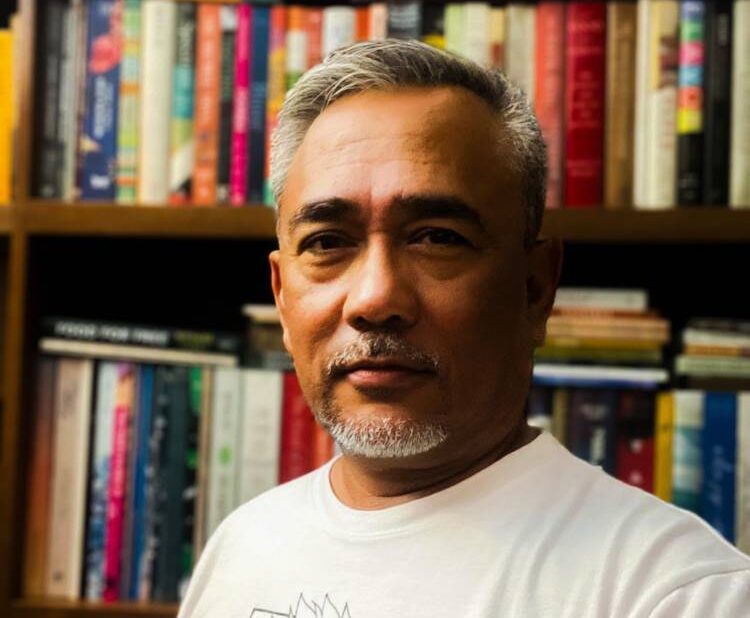

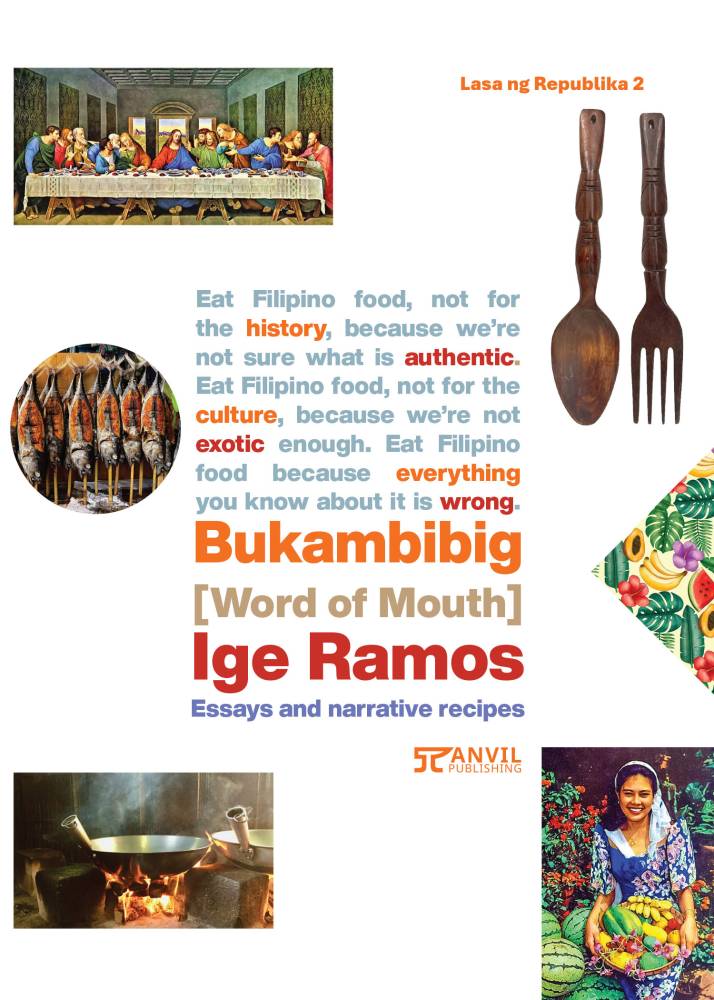

“Makurilyu”—the Kapampangan fear of running out of food, of falling short as a host, of being remembered for what was missing—is explained in depth by Ige Ramos in his book “Bukambibig.” Encountering the word felt less like a discovery and more like recognition. Suddenly, my mother—and so many Filipino tables—made perfect sense.

In Pampanga, food is never casual. Cooking is care made visible. A table reflects how much thought and attention a host gives to the people gathered around it. Running out of food is not just inconvenient; it is embarrassing—nakakahiya!—the sort of thing remembered long after the meal is over.

As Ramos puts it simply, it isn’t hunger that people fear. It’s falling short. Makurilyu explains familiar behavior: cooking one dish too many, keeping pots warm even when everyone insists they are full, worrying quietly while guests eat. It explains why hosts hover instead of sitting down, why pabaon is handed out at the door—and why there is always one more dish set aside, just in case. “Puwede naman pa-init at kainin bukas.” You can reheat it and eat it the next day.

But this fear doesn’t mean waste. It means care. Recipes are cooked again and again until they’re right. Dishes are refined not to impress, but to reassure. Abundance becomes a way of saying: You are welcome here, you matter, our house is your house.

Under makurilyu, feeding people becomes a commitment. No one will be embarrassed. No one will be deprived. No one will be forgotten.

Caring for people through food

Food carries memory and reputation, a source of family pride. It is an act of kindness, expressed through careful preparation and the instinct to take care of people.

In “Bukambibig,” makurilyu sits alongside other essays that shape how Filipinos cook, eat, and talk about food. Ramos isn’t interested in polishing or defending our food. He listens to kitchens, markets, family tables—and lets our food be seen as it is: lived, passed on, and beautiful.

“Bukambibig” offers permission: to question assumptions, to sit with contradictions, to allow food to mean different things to different people. It reminds us that cuisine isn’t only what ends up on the plate, but everything that surrounds it.

Let’s continue the conversation this Saturday, as “Bukambibig” is launched at Manila House at 3 p.m. Meanwhile, at 5 p.m., join us for “Fiesta Under the Stars,” where chefs Tatung Sarthou, Gel Salonga-Datu, Tina Legarda, Miggy Moreno, Jay Jay Sycip, and yours truly will prepare a spread inspired by coconut, citrus, and chilies.

The evening will also be capped with Noel Cabangon serenading us with familiar, much-loved OPM.

For reservations and inquiries, contact +63 917 816 3685 or +63 917 657 2073 or email reservations@manilahouseinc.com

Sisig, as told in “Bukambibig”

Ramos writes about sisig the way people actually talk about it—with pride, opinions, and a fair amount of debate. Yes, it’s Kapampangan. Yes, there are strong ideas about what belongs in it. And yes, those ideas are still being argued over.

Rather than fixing sisig in place, the book treats it as lived food. It grew out of thrift and resourcefulness, and traveled far beyond Pampanga, picking up variations along the way. Like many Filipino dishes, sisig depends less on strict measurements and more on instinct—knowing when it tastes right.

Sisig

Ingredients

1 kilo pork belly (lechon kawali cut)

Water

1 Tbsp rock salt

1 onion, cut into wedges

1 medium onion, finely chopped

Oil for deep frying

4 cloves garlic, finely chopped

150g chicken liver

2 to 3 green chilies, sliced

1 to 2 Tbsp light soy sauce

2 to 3 Tbsp calamansi juice

Freshly ground black pepper, to taste

Procedure

1. Begin by preparing the pork belly. Place 1 kilo pork belly (lechon kawali cut) in a pot with enough water to cover, 1 Tbsp rock salt, and 1 onion, cut into wedges.

2. Boil the pork until it becomes tender, then remove it from the water and allow it to drain. Let it cool completely and air-dry on a plate or tray.

3. Heat a shallow pan with enough oil for deep frying. Fry the pork belly until crisp and golden, then let it cool before chopping it into small, bite-sized morsels.

4. In a separate pan, sauté 4 cloves of garlic, finely chopped, together with 150 grams of chicken liver, chopped, until thoroughly cooked. Remove the pan from the heat, then incorporate 1 medium onion, finely chopped, the crispy pork, and 2 to 3 green chilies, sliced.

5. Season the mixture with 1 to 2 Tbsp light soy sauce, 2 to 3 Tbsp calamansi juice, and freshly ground black pepper to taste.

6. Present the dish on a sizzling plate, as is commonly done in karaoke bars, and refrain from adding egg or mayonnaise if you wish to keep it traditional.