Quiet Pangasinan town weighs cost of power

(First of three parts)

LABRADOR, PANGASINAN—This quiet coastal town on the western edge of Pangasinan sits where hills loosen their grip and the land yields to the wide breath of the Lingayen Gulf, a place where life is shaped by water and soil.

At dawn, fishing boats return from an all-night haul, their outriggers tracing gentle lines against the horizon as nets heavy with the night’s labor are pulled onto the sand.

Farmers walk to the fields at sunrise and sunset, tending rice or vegetable crops depending on the season. Others make a living crafting brooms and “sawali,” while a few beach resorts dot the tranquil shoreline.

Life here has long been unhurried and unharried—until what some residents now call an “environmental monster” stared them in the face: a proposed nuclear power plant.

For years, opposition was barely audible, drowned out by booming promises from project proponents—near-free electricity, lower power rates nationwide, and economic bonanza that would lift the town from stupor.

But the silence has broken.

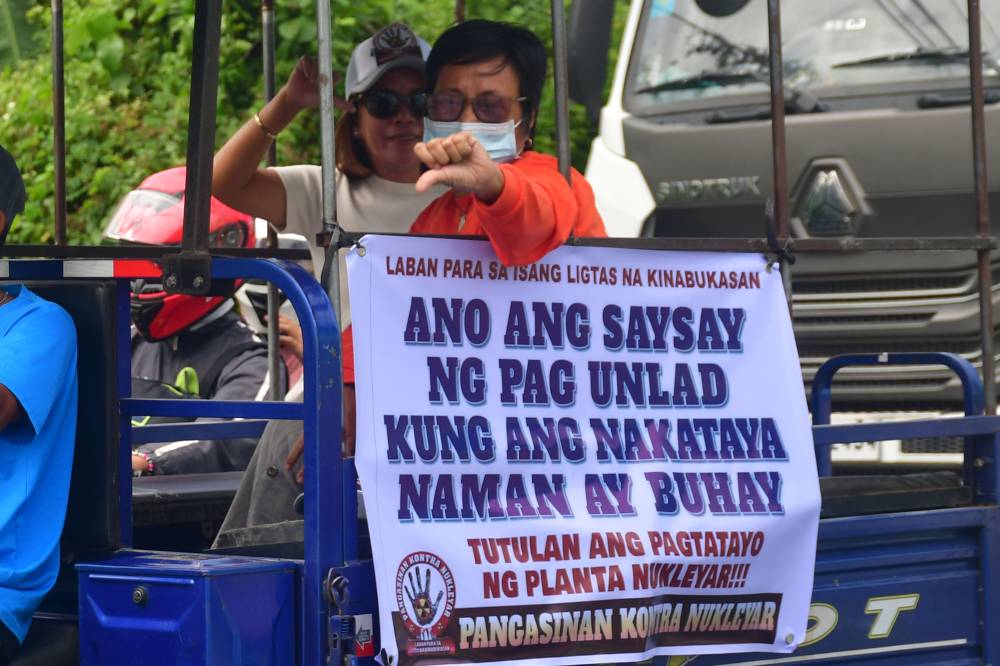

What was once a motley group of residents quietly resisting the project has grown into a more unified movement, one that warns the nuclear plant could erase Labrador from the map.

P225-B proposal

It is precisely Labrador’s geography—mountains and sea—that made it attractive as a proposed nuclear power plant site, according to Pangasinan Second District Rep. Mark Cojuangco.

“Why Labrador? Because it has mountains and the sea,” Cojuangco says in an earlier interview.

He adds: “The mountain allows us to elevate the plant 15 meters above sea level to make it tsunami-proof, and seawater is needed to cool the plant. Cooling towers are expensive, and freshwater in the Philippines is limited so we can tap sea water.”

Cojuangco has been pushing for nuclear power for 18 years, arguing that it is the solution to the country’s chronic electricity problems, which he says drove away investors.

“All administrations after 1986 failed to solve the electricity crisis,” he notes.

“Power here is expensive and unreliable. We lost the opportunity to attract investors during the Southeast Asian boom of the late 1980s to early 2000s. We never experienced the double-digit growth our neighbors did,” the lawmaker explains.

Since winning a congressional seat, Cojuangco has set his sights on Labrador as host to a 1,000-megawatt, P225-billion nuclear power plant, proposed to be built on about 120 hectares. The plan involves four small modular reactor units, each occupying roughly 40 ha.

During a Senate committee on science and technology hearing on Senate Bill No. 1206 (Philippine Nuclear Liability Act) on Jan. 22, Department of Energy Director IV Patrick Aquino says Labrador was among the sites listed by the Nuclear Energy Program–Inter-Agency Committee (NEP-IAC) after physical inspections and evaluations.

According to Aquino, other potential sites include areas in Bataan, Camarines Norte, Puerto Princesa in Palawan and Masbate.

Local leaders’ stance

Cojuangco, who chairs the House special committee on nuclear energy, has gained the support of town and barangay officials in Labrador.

Former Mayor Ernesto Acain endorses the project, citing the town’s “strategic location.”

His successor, Mayor Noel Uson, has expressed conditional support for nuclear energy but stressed that “safety and security must always come first.”

Pangasinan Gov. Ramon Guico III echoes caution, saying the province is open to nuclear energy but needs further study.

“The primary consideration is the safety of the people,” Guico shares.

“Nuclear energy is a sensitive issue. While cheaper electricity is possible, safety must be assured, and the site must not be prone to earthquakes or other natural hazards,” the governor remarks.

In neighboring La Union province, Gov. Mario Eduardo Ortega said residents were divided on the issue.

“This is not for one person to decide,” he asserts. “We have to go back to the people and ask whether they are for or against it.”

La Union, whose towns once formed part of Pangasinan, shares the waters of the Lingayen Gulf with Pangasinan.

“From birth, we take risks and make decisions,” Ortega stresses. “Whichever way it goes, we live with the outcome.”

People opposing the plan ask why a town of just 30,000 people occupying less than 10,000 ha should shoulder the risk of an environmentally critical project.

Why Labrador?

Hipolito Mislang, 93, a farmer-leader, said Cojuangco himself once described Labrador as the poorest town in Pangasinan—a fact Mislang believes made it an easy target.

“They say the plant will lift Labrador from poverty,” Mislang says. “But what will be destroyed? Everything. We are an agricultural town. We have farms, fishponds and a healthy environment. Once you damage the environment, agriculture collapses.”

Young schoolteacher Jericho Lontoc, 23, warned that the plant’s 16-kilometer exclusion zone would render Labrador uninhabitable.

“From Lingayen to Sual is only about 18 to 20 km,” he shares. “If a 16-km danger zone is enforced, Labradormdisappears.”

For years, Mislang and Lontoc were among the few voices raising alarms—until the issue reached national attention and Labrador was thrust into the national consciousness.

In December 2025, Catholic leaders led by Lingayen-Dagupan Archbishop Socrates Villegas issued a pastoral letter strongly opposing the project, citing seismic risk, radioactive waste and moral responsibility.

Church enters the debate

They warned of the Philippines’ location along the Pacific Ring of Fire, the absence of permanent waste-disposal solutions and lessons from the Fukushima disaster.

“Following the 2011 Fukushima catastrophe,” the letter states, “the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of Japan called for the abolition of nuclear power due to its insoluble dangers to life, livelihood and the environment.”

Their reasons include the country’s vulnerability to disasters such as earthquake and supertyphoons, the town’s proximity to the East Zambales fault line, and lack of secure and long term solution for disposal of radioactive wastes that remain deadly for thousand of years.

The church leaders instead call for “renewable energy and embracing the abundant renewable energy sources God has provided us.

“The solution to our energy woes exists in strict and urgent implementation of the Renewable Energy Law, which has been in effect since 2008. The solution is not in building dangerous technologies which would bring more profit to private corporations, but put our people in harm’s way,” they declare.

Within days, 33 bishops have signed the letter. Their message was unequivocal: not in Pangasinan—and not anywhere else.

A month later, after a Mass at a local church, about 500 residents signed a manifesto opposing the nuclear power plant in Pangasinan.

******

Get real-time news updates: inqnews.net/inqviber