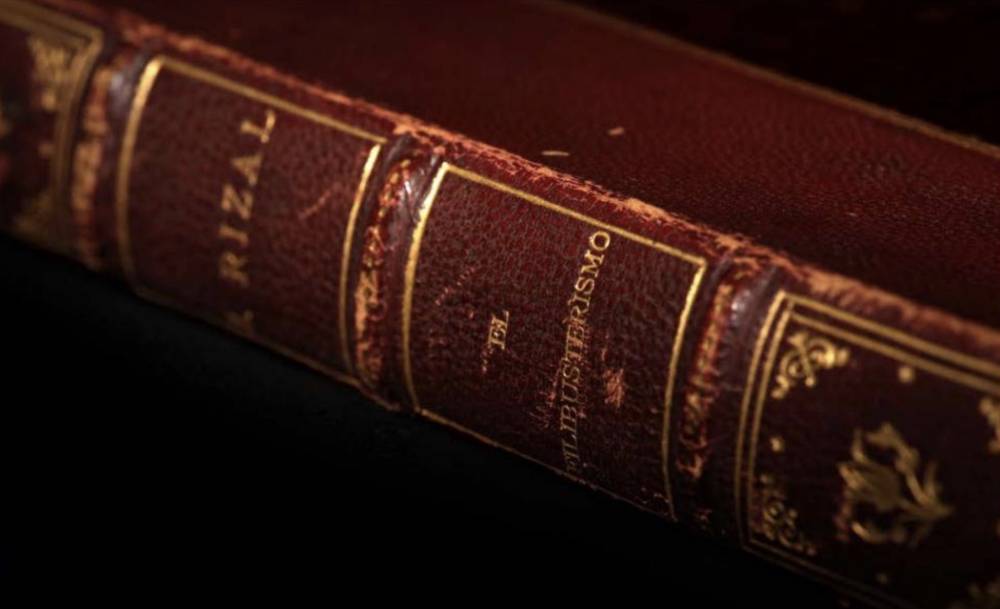

Once banned, signed copy of Rizal’s ‘El Fili’ up for auction

A copy of one of the most important books in Philippine history, signed by the author and country’s national hero no less, will be up for auction on Valentine’s Day.

The first edition of “El Filibusterismo,” printed in Ghent in 1891 and signed and dedicated by José Rizal to his close friend and fellow ilustrado, Dr. Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera, will be offered by Leon Gallery at its annual Asia Cultural Council (ACC) Auction this Saturday.

With a floor price of P5 million, the volume is among the rarest surviving copies of Rizal’s second novel—and may well be the very first copy off the press.

The auction coincides with the 125th anniversary of the publication of “El Filibusterismo,” a milestone largely unnoticed outside scholarly circles. Once banned, hunted down, and feared by colonial authorities, Rizal’s most radical novel now returns to public view under the formal lights of the auction room, its survival mirroring the nation’s long passage from repression to remembrance.

Printed at the Boekdrukkerij F. Meyer–Van Loo on Vlaanderenstraat in Ghent, the “Fili” emerged under far harsher circumstances than those surrounding “Noli Me Tangere.”

By 1890, Rizal was no longer the celebrated ilustrado of Parisian salons. His family had been violently evicted from their lands in Calamba; his father and brother were exiled; and the income that sustained him abroad had collapsed. Compounding these losses was the news that Leonor Rivera, unaware that Rizal’s letters had been intercepted, had married another man.

These experiences darkened the novel. Where the “Noli” introduced the hopeful reformist Crisóstomo Ibarra, “El Filibusterismo” returned him as Simoun, hardened into a figure of vengeance. The narrative traces land dispossession through the tragedy of Kabesang Tales, the moral suffocation of María Clara within a convent, and a society corroded by hypocrisy and abuse. It ends not in triumph but in failure, closing with Padre Florentino’s stark reminder that personal revenge can never substitute for a just and moral cause.

Timely intervention

The book’s production echoed its themes of deprivation.

To cut costs, Rizal left Paris after the 1889 Exposition Universelle, moving first to Brussels and then to Ghent. He lodged near the press with José Alejandrino, later a general of the First Philippine Republic. Together they corrected proofs, skipped meals, and stretched remittances from compatriots abroad. At his lowest point, Rizal pawned his mother’s jewelry and lived on tea and biscuits, threatening to burn the manuscript before Valentin Ventura’s timely intervention saved the book.

The finished book was slimmer than the “Noli” and printed in fewer copies—circumstances that would later heighten its rarity.

The book was dedicated to the priests Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, who were executed in 1872. Rizal framed the novel as a moral indictment of colonial injustice, honoring the martyred priests as victims whose unproven guilt exposed the violence of empire.

Colonial authorities, who immediately grasped the novel’s danger, swiftly banned it.

Possession and distribution were punishable offenses. Accounts suggest that a shipment of some 800 copies—possibly half the print run—bound for Hong Kong was confiscated, lost, or destroyed.

First completed copy

Against this history, the copy to be auctioned by Leon Gallery carries exceptional weight.

Signed and dedicated in Rizal’s hand—“A mi querido amigo el doctor T. H. Pardo de Tavera”—and dated Sept. 16, 1891, it predates the novel’s commonly cited release date.

Scholars believe it may be the first completed copy off the press, personally handled by Rizal and sent to one of his closest intellectual allies. Its provenance is reinforced by Pardo de Tavera’s ex libris and name stamp on the title page.

For collectors, the volume is an irreplaceable artifact; for historians, a biographical document capturing the convergence of literature, personal despair, and political resistance. Unlike the reformist “Noli,” “El Filibusterismo” issued a darker warning. As Rizal’s confidant Ferdinand Blumentritt noted, filibusterism was the inevitable outcome of sustained oppression.

When the hammer falls on Feb. 14, Leon Gallery will mark more than a sale. It will honor a book written in hunger and heartbreak, preserved against the odds, and still—125 years on—capable of unsettling and instructing a nation.

The auction also features a rare early drawing by Rizal, “Untitled (La Niña Mestiza),” a crayon portrait executed around 1876–1877 while he was a student at the Ateneo Municipal.

Also under the hammer is Isabelo Tampinco’s alabaster sculpture “Untitled (Angel Writing in a Book),” consigned from the heirs of Maximo Viola, the ilustrado who financed the publication of the “Noli.”

Completing the offerings is a complete first-edition, 14-volume set of Fray Juan de la Concepción’s “Historia General de Philipinas” (1788–1792), accompanied by the Murillo Velarde map. Priced at P2.4 million and retaining all 10 engraved maps, including the iconic Philippine map by Nicolás de la Cruz Bagay, the set ranks among the rarest and most comprehensive early histories of the archipelago.

******

Get real-time news updates: inqnews.net/inqviber

‘Allocable’ funds: Resurrected pork barrel