‘Isang Pasa Tiempo’ docu on Avellana, Conde restored after 40 years

“Isang Pasa Tiempo,” a 42-year-old thesis film featuring rare interviews with the late National Artists for Film Lamberto Avellana and Manuel Conde, has been restored, digitized and then screened at the Cinematheque Center of the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP) over the weekend.

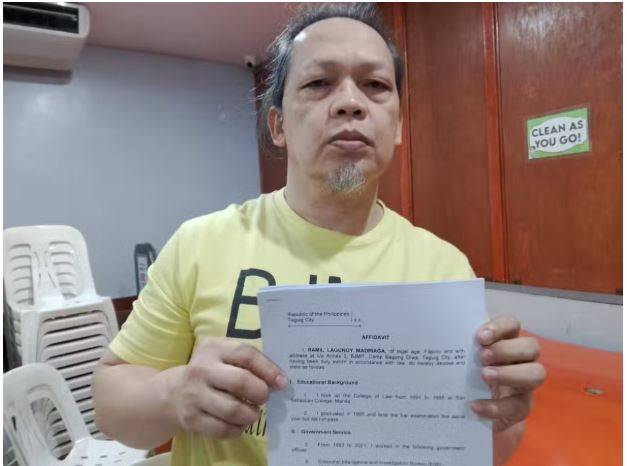

The 23-minute documentary was created in 1982 by De La Salle University (DLSU) communication arts majors Chiqui Escareal-Go, Cynthia Obaldo-Herrera and Anna Cousart-Domingo. Originally produced in super 8mm format, the film talks about the origins of the defunct production company, LVN Pictures, and its contributions to the film industry.

“Isang Pasa Tiempo,” or “pastime,” was how LVN founder Sisang de Leon referred to filmmaking. The docu also features actual interviews with filmmaker Manuel Silos, LVN actors Nestor de Villa and Rosa Rosal, and Dona Sisang’s son Manuel de Leon Sr.

“As the wise say, ‘Life can only be understood backwards,’ which is why looking at the past could be an enlightening journey that allows us to better appreciate and understand our present circumstances. This is also why the FDCP welcomes events such as this. To shine a spotlight on the significant contributions of prominent institutions, such as the LVN Pictures to our industry,” said FDCP chair Tirso Cruz III prior to presenting “Isang Pasa Tiempo” to the public once again at the Cinematheque Center on Kalaw Street in Manila. (Its last public showing was at the 1983 Experimental Cinema of the Philippines, where it won third place in the student documentary category).

“We are fortunate to watch the film today, however short it is, because of its value. We get to see and hear some of the filmmakers who have contributed to the development of Philippine cinema and get a glimpse of LVN movies even just through stills,” said novelist, journalist and filmmaker Clodualdo del Mundo Jr., who was also the three students’ thesis adviser at the time in DLSU.

“The short film remains relevant and viable today because it features filmmakers and their films that have—to use Fr. Bert Ampil’s words—‘somehow touched the Filipino soul.’ Thank you for restoring your film and sharing it with audiences of today and tomorrow.”

‘Sense of the past’

Film and TV director Jose Javier Reyes, who is also FDCP consultant and a professor of the three back then, told film students present during the screening: “There were two National Artists for Film interviewed in this docu. How many docus do we have that feature two artists as legendary as these two captured in a thesis film? This, more or less, shows the importance of thesis films.”

Reyes continued: “They give us a sense of the past that we tend to neglect. With globalization, Filipino filmmakers’ minds are also screwed up with all kinds of influences. This, somehow, waters down our very identity. We must acknowledge the importance of Avellana and Conde, and of Gerry de Leon, Lino Brocka, Marilou Diaz-Abaya, Kidlat Tahimik and all the others who have built that bridge so we can cross generations and reach this point.”

Cruz reported that more producers are now submitting copies of audiovisual materials to the FDCP for safekeeping. “We would feel sad whenever we encounter material that can no longer be saved. It’s nice that producers are starting to trust us to take care and preserve their raw materials. Hopefully, in a year’s time or so, we will be able to complete our new building. This means more storage space for our archive,” the FDCP chief announced.

Go said she consulted filmmaker Mike de Leon, also one of their college professors, for the restoration. He recommended a laboratory in Italy called L’Immagine Ritrovata, which he said was a supplier that gave him a “substantial discount.”

“One of the questions he asked me was, ‘Do you expect me to fund this?’ I said, ‘After 40 years, we now have work and will be able to afford that.’ I even volunteered to make my driver bring the material to Ritrovata, thinking that this was in Cubao,” Go recalled, laughing.

‘Mind-blowing’

“All we wanted was to graduate from Com Arts,” said Herrera. “We were kids then, three 20-year-old girls. However, just being here right now, watching it, and celebrating with everyone … it’s mind-blowing. I love my two friends for making this happen.”

“Of course, we were starstruck at the time because they were big names. Their characters would come out when you see their offices or homes. Manuel Silos was an inventor. He loved to tinker. We saw that he had different lenses, located all over his house—from the sala up to the dining area,” recalled Domingo. “Inside Manuel Conde’s home in San Pablo, Laguna, we saw a huge portrait of Juan Tamad. He immortalized the character in a huge painting. Avellana was very accommodating. We went to see him at the La Mesa Dam (where he was shooting ‘Waywaya’), and then he volunteered to drive us back to Makati.”

Domingo continued: “When we were doing it in 1982, we said, ‘Let’s just do something worthwhile of the past.’ Upon review of the film now, it still pertains to how film was in the past, but also of how you want to preserve it for the future, and where filmmaking should go in the future.

“The beauty of filmmaking is in using the right format and content, that’s what we were taught in Com Arts. When you create something, you look for significance in what you do. What story do you want to say and how does it relate to your life and the lives of others? In the end, that’s just what we wanted to do—to make a difference.”