Defense to offense: Switch focus from flood control to irrigation

Why do we treat water as our enemy? For decades, the country has prioritized walls and channels to block floods, neglecting the fact that water is our most powerful ally, especially for food security. Instead of making water work for us, we have spent billions trying to make it go away.

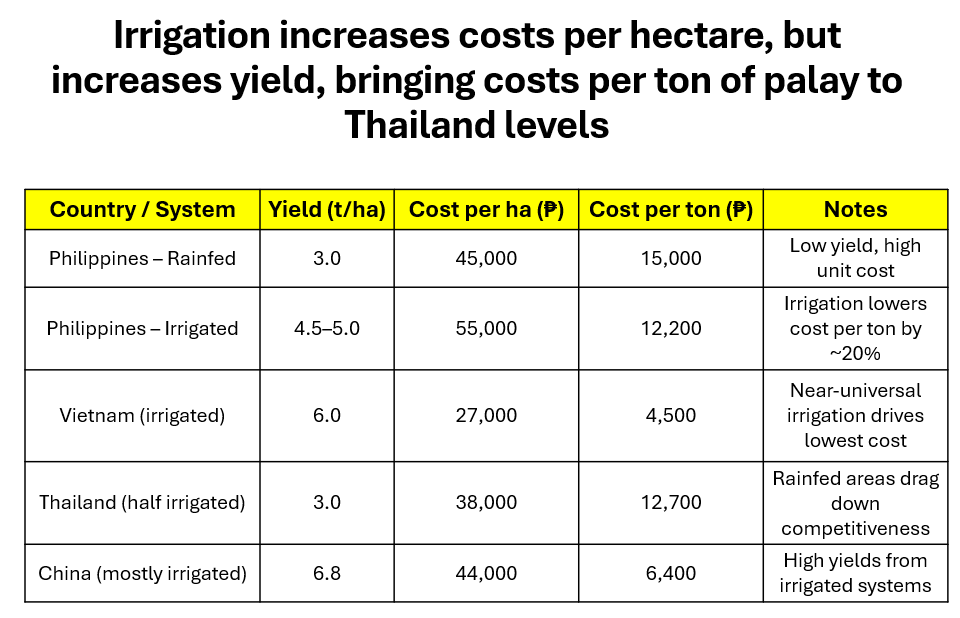

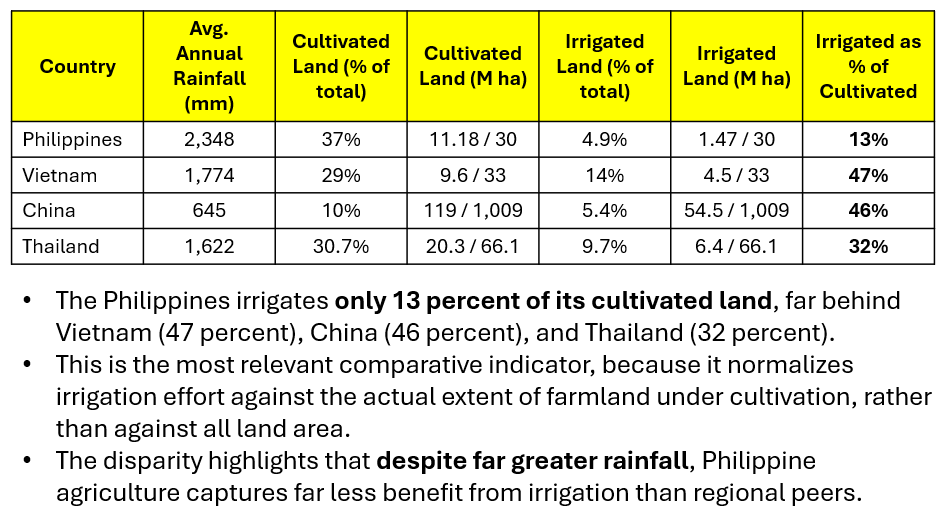

The Philippines receives one of the highest annual rainfalls in the world at about 2,348 millimeters. Yet farmers still struggle with water. Only 2.15 million hectares of irrigable land are currently supported by irrigation systems, compared with a potential of 3.1 million hectares. That gap means agriculture still lurches from drought to flood, with rice production heavily erratic.

The irony is stark. On one hand, the national budget for 2025 allocates P346 billion to flood control. On the other hand, irrigation receives only P69 billion, five times less, even though flood control merely curbs economic loss while irrigation builds productivity.

We have also undone a vital funding mechanism. The Free Irrigation Service Act of 2018, though well-intentioned, eliminated the irrigation service fee. That stripped irrigators’ associations of a small but crucial income for day-to-day maintenance such as desilting, canal repair and gate fixing. Now, the National Irrigation Administration (NIA) must rely fully on the annual budget, with repairs delayed by red tape, politics and shortage.

There was a better model. The NIA once deployed institutional development officers nationwide. These officers were human capital embedded inside engineering. They organized farmers into associations, trained them in governance, kept the books and built ownership. The result was better irrigation management and higher system reliability.

It is time to revive that model, but modernize it. Irrigators’ associations should be empowered to collect a modest irrigation contribution, fully ring-fenced for light maintenance. This would not be a return to punitive fees but a community fund for essential upkeep.

On top of that, the NIA should adopt a performance-based incentive system. Associations that exceed benchmarks – such as covering more service area, improving water delivery efficiency, increasing cropping intensity or maintaining clean accounts – should earn rewards such as equipment, training slots or reinvestment grants.

Financing irrigation must evolve as well. Every official development assistance loan for irrigation should include a bond component coursed through the NIA. Coupons would finance perpetual operation and maintenance, and principals would roll over. This would create a permanent endowment, finally breaking the cyclical build-neglect-rebuild trap.

We have already tried using bonds to finance irrigation. In 2006 and again in 2009, the National Development Company issued a total of P5.5 billion in Agri Agra bonds, on-lent to the NIA for rehabilitation works. These funds restored some 33,000 hectares and improved services for another 20,000. The approach showed that capital market instruments could move quickly and mobilize large sums for irrigation at a time when budget allocations were scarce.

But there were also lessons

The Agri Agra bonds delivered new hectares, but not permanent maintenance. Yields improved only modestly because the systems, once rehabilitated, again lacked steady funds for upkeep. In 2019, the national government had to settle the debt in full, using scarce fiscal resources. The experiment proved that bonds could finance irrigation, but without a mechanism to reinvest coupons and protect assets, the gains were not locked in.

These experiences should guide us today. If we are to borrow again for irrigation, we must design financing that does not stop at construction. Bonds should not only build canals but also create permanent maintenance endowments. Otherwise, we will repeat the cycle: build with borrowed money, neglect it for lack of funds and then bail out with taxpayer money.

These reforms could transform agriculture. Already in 2025, palay production is on track to meet or exceed 20.4 million metric tons (MT), driven by strong first-half output of 9.08 million MT. This means production is stabilizing. Real gains, however, will come from irrigation expansion and improved productivity.

Water is not an adversary to wall off. It is an asset to cultivate. It can harvest not just floods but also everybody’s food security and prosperity. If the country harnesses the combined power of community-based management and durable financing, it can not only meet but also sustain record harvests. Flood control helps protect. Irrigation empowers.

The author is a former congressman of Albay and also previously served as its provincial governor. He also earlier served as chief of staff of President Gloria

Macapagal-Arroyo. Before entering politics, he was an award-winning stock market analyst who headed the Philippine research team of UBS and ING. He currently chairs the Institute for Risk and Strategic Studies Inc./Salceda Research.