‘Decarbonizing’ PH a race against time—but ‘we should do it properly’

Key players in the country’s energy sector are running against time to “decarbonize” the industry that continues to be a huge contributor to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Climate-vulnerable countries, such as the Philippines, remain at the mercy of stronger rains, warmer oceans, and rising sea levels year after year due to global warming caused by such emissions.

“The energy sector is one of the biggest contributors of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. And [there is a] need to decarbonize the power industry. Renewable energy is essential to meeting the global climate goals,” said Rene Fajilagutan, general manager of Romblon Electric Cooperative Inc.

Fajilagutan was one of the speakers at the second Inquirer ESG Edge Initiative forum held at the Ateneo de Manila University School of Law on Nov. 29.

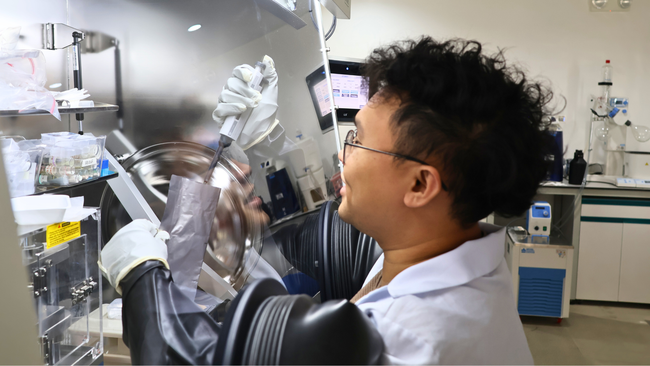

Joey Ocon, an engineering professor and scientist at the University of the Philippines Diliman and cofounder of Nascent Batteries, a young firm that works on energy storage solutions, stressed the role of nonpollutant energy sources in cutting back carbon dioxide emissions.

“There are a lot of ways to remove carbon dioxide or at least reduce the pace of increasing carbon dioxide emissions in our atmosphere. One of the biggest weapons we have is renewable energy,” said Ocon, who also served as a resource speaker at the second installment of the Inquirer ESG Edge forum.

But while transitioning to renewable energy sources is the obvious solution to the worsening impact of climate change, the shift should be done “with the right mix of technologies,” the “right timing,” and in the “right context” for the Philippines, according to the forum speakers.

“We shouldn’t necessarily rush. I don’t think that they should take away from the sort of the emergency that is needed for the energy transition because we are very time-bound,” said environmental scientist John Charles Altomonte of the Ateneo School of Government. He was referring to the Philippine Energy Plan, which declares a target of getting 35 percent of renewable energy sources into the country’s total energy generation mix by 2030 and at least 50 percent by 2040.

But Altomonte recognized the sense of urgency to the climate crisis, with the yearly climate scenario in the country continuing to indicate that “we’re very much underestimating the impacts [of climate change.]”

“It’s a very complex system. It’s very hard to transition; it’s very hard to plan and to model, so we should do it properly. But we should also try to keep in mind these global timelines,” he added.

For one, renewable energy adoption policies for small players in the industry need to be revised to become “encouraging,” according to Fajilagutan.

“If I will build my local plant, an embedded power plant, in my franchise area, with a size of 1 megawatt, I will wait for several years to get the approval [of tariff rates] from the ERC (Energy Regulatory Commission),” he said.

ERC issues feed-in tariff rates to incentivize clean energy developers with a steady stream of cash flow into their power projects. But the rates vary per type of renewable energy source and require a minimum installation capacity target to be eligible.

“How can we achieve the aspiration of 35 percent (by 2030) if we don’t change the policy?” asked Fajilagutan. “I think it’s a matter of developing a helpful policy for these small players in the industry.”

For Fajilagutan, an engineer with over 30 years of experience in rural electrification, “it’s a matter of changing the mindset.”

Net-zero company

Ayala-backed ACEN Corp. has vowed to become a “net-zero GHG emissions company” by 2050 by divesting its coal assets and reinvesting them into cleaner energy sources.

“As a result, we have grown our renewable portfolio from 70 megawatts in 2016 to 6.8 gigawatts of capacity today,” said Irene Maranan, ACEN senior vice president and head of corporate communications and sustainability.

“ACEN aspires to manage 20 gigawatts of renewables capacity by 2030, and net zero GHG emissions by 2050. And aside from scaling up renewables, the company has been pioneering initiatives in their early coal retirement,” she added.

Any impacts of the planned shutdown of the 246-megawatt South Luzon Thermal Energy Corp. coal plant in Batangas would be “negligible,” said Maranan, because it would be replaced by a 400-megawatt integrated renewables energy storage system.

“It’s a combination of solar or wind with battery storage to address the intermittent issues of the renewable [energy] plan,” she noted, adding that the replacement capacity would “ensure that the foregone coal plant output is matched 100 percent.”

“The impact on the grid is negligible given that renewables intermittency is mitigated by the energy storage system, and the output is reliable and dispatchable,” she explained.

In addressing the climate crisis in developing nations like the Philippines, it is crucial to focus more on adaptation rather than mitigation, according to Pedro Maniego Jr., chair of the Institute of Corporate Directors and senior policy adviser of the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities.

“We should concentrate on adaptation because that’s our problem. Sea levels are rising; typhoons are getting stronger. We have more rains… and the [occurrence] of El Niño, La Niña… All of this needs adaptation,” said Maniego.

For Ocon, vulnerable countries should continue to lobby countries responsible for the billions of tons of CO2 emissions.

“We’re very vulnerable. We have limited capital… Billions of dollars should be invested in countries like the Philippines that are undergoing transition and also will be affected by the stronger typhoons and other natural hazards,” he said.

The climate talks at the 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) in Baku, Azerbaijan, ended on a dismal note after wealthy nations, including the United States and those from the European Union, pledged to raise $300 billion a year for climate financing.

The amount was way below the at least $500 billion many developing countries had demanded from rich countries, which continue to be the world’s biggest GHG polluters.