Government policies, reforms rewire PH telco landscape

From a sector once dominated by a single operator to a market repeatedly reshaped by political intervention and the entry of deep-pocketed local and private companies, the telecommunications industry in the Philippines has seen profound growth through the decades.

What now appears to be a competitive market emerged from a long process of opening up an industry that, for much of its history, was dominated by a monopoly.

The Philippine Daily Inquirer has been there to record these significant shifts over 40 years.

Monopoly

PLDT Inc., then still the Philippine Long Distance Company, secured near-total control of the market in 1981 after acquiring the assets and liabilities of the Republic Telephone Co., the country’s then second-largest operator.

This unfolded against the backdrop of development plans to expand telephone access and raise density across cities and municipalities by 1998.

But after Marcos’ grip on power waned, so did PLDT’s unchallenged hold on the industry.

Under the first Aquino administration, the firm was reprivatized and the industry was deregulated. This exposed the consequences of monopoly, such as chronic underinvestment, slow expansion and a mountain of telephone backlogs.

In 1989, there were only 506,000 available phone lines in a country of 60 million.

To address the shortage, the government passed the Municipal Telephone Act, which aimed to establish public calling stations in 10,120 villages nationwide, with their operation open to private firms.

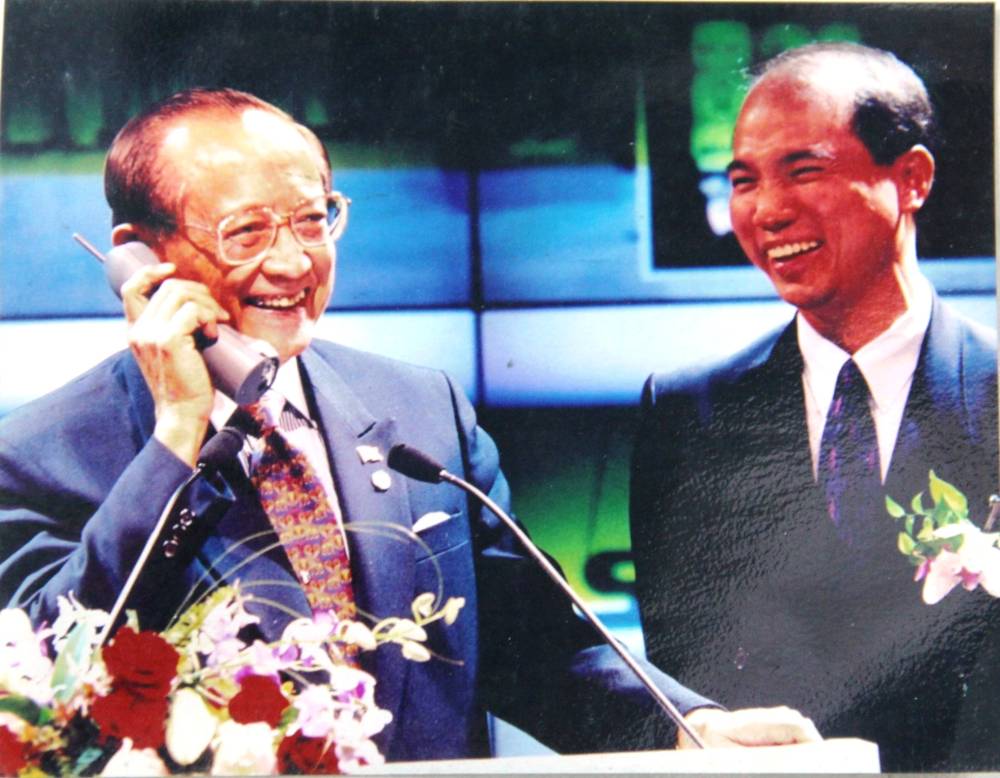

Ramos reforms

But perhaps the most sweeping structural reforms came only under former President Fidel Ramos.

In 1993, he issued Executive Order No. 59, which ordered compulsory interconnection among all carriers, ending PLDT’s ability to isolate rivals from its network. EO 109 and the Public Telecommunications Policy Act soon followed, prying the market open and mandating service rollout in underserved areas.

And worked it did, as installed lines jumped to about 6.5 million in 1998 from just over 1 million in 1993. New entrants invested heavily in switching systems, transmission networks and early mobile infrastructure. This, despite strong pushback from PLDT and its allies.

Meanwhile, Globe Telecom, the first telco firm to list on the Philippine Stock Exchange in 1975, launched its digital GSM services in the mid-1990s. Text messaging, international roaming and prepaid SIMs exploded, pushing mobile subscriptions to 86.15 million by the end of 2010.

Duopoly forming

However, a wave of consolidations in the 2000s ultimately shifted power back to two dominant players.

At the turn of the millennium, PLDT acquired Smart Communications, converting the fast-growing mobile operator into a wholly owned subsidiary through a share-swap arrangement.

The deal gave PLDT—historically focused on fixed-line telephone operations—a commanding presence in mobile services, which were rapidly surpassing landlines as the primary mode of communication.

A decade later, in 2011, PLDT purchased Digital Telecommunications Philippines Inc., owner of Sun Cellular, for P74.1 billion, absorbing the operator that had forced industry-wide price cuts through its unlimited call-and-text promos.

With no serious third competitor left standing, the Philippine market settled into a duopoly. For consumers, this translated into slow broadband speeds, congested networks and service costs that lagged behind regional standards, fueling persistent calls for a new major player.

Third player

Attempts to break the duopoly began long before the eventual arrival of a third player.

In 2007, the Arroyo administration signed a $329-million National Broadband Network deal with China’s ZTE Corp., but it collapsed after allegations that the contract was overpriced by $130 million to cover kickbacks.

Pressure for a new player grew louder under the administration of Pres. Rodrigo Duterte, which moved to break the long-running PLDT-Globe duopoly that was then serving 100 million mobile subscribers.

A consortium led by Davao businessman Dennis Uy and China Telecommunications Corp. won the selection process, using the dormant franchise of Mindanao Islamic Telephone Co. to register what would become DITO Telecommunity.

In the background, San Miguel Corp.’s efforts to offer a viable third telco player fizzled as a deal with Australia’s Telstra Corp. Ltd. fell through, forcing the Ramon Ang-led conglomerate to sell over $1 billion worth of equipment to PLDT and Globe.

What now

As of 2025, PLDT and Globe still control about 80 percent of the broadband market, while DITO has grown to about 250,000 fixed-wireless subscribers. Another emerging force in the fiber broadband segment is Converge ICT.

Changes to the landscape are seen to accelerate after the Konektadong Pinoy Act lapsed into law in late August. This measure removes the legislative franchise requirement for the data transmission industry, simplifies licensing and encourages infrastructure sharing, virtually opening the door for new domestic and foreign players.

According to the Department of Information and Communications Technology, two to three telco firms are expected to enter the market after the law’s implementing rules and regulations are signed.

If everything goes as planned, the law could deliver some of the most consequential challenges yet to entrenched Philippine telco players. But as history suggests, any effort to reshape the country’s telco landscape has never come without resistance.