SPECIAL REPORT: ‘PH’s national debt at its ‘maximum level’—Gatchalian

- (Conclusion)

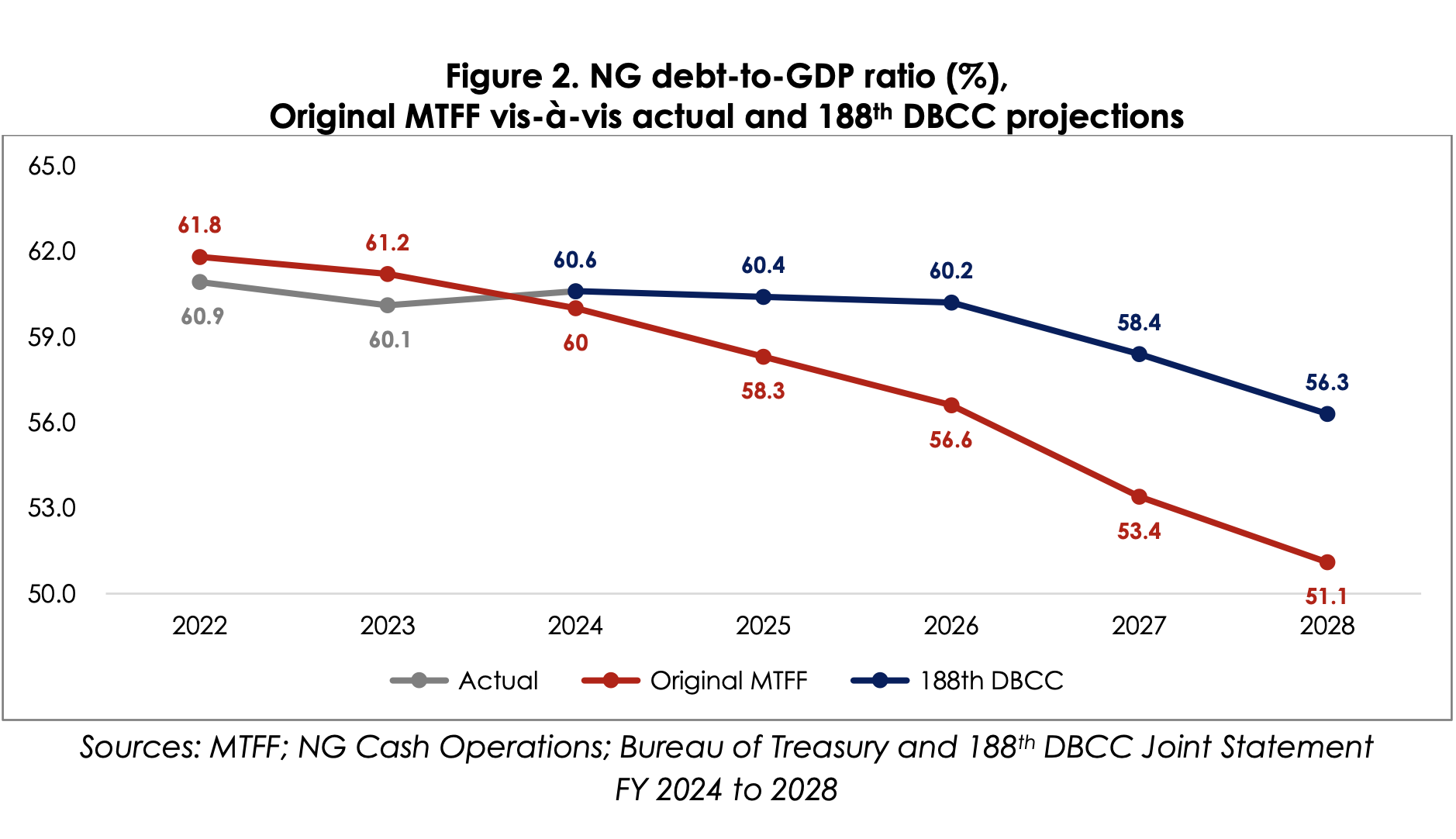

The government is keeping the national debt level elevated for two more years, revising an earlier target to pare it down this year to the internationally accepted threshold of 60 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) for developing countries.

The recent revision of the government’s fiscal consolidation plan is causing concern for Sen. Sherwin Gatchalian, chair of the Senate Ways and Means Committee and former chair of the Economic Affairs Committee.

In an exclusive interview with the INQUIRER, Gatchalian cautioned the government against postponing the original target set in 2022 when Congress adopted the Medium-Term Fiscal Framework (MTFF). He said that instead of holding on to the debt-to-GDP ratio above the 60 percent threshold, the government should actively reduce it to 50 percent.

Ultimately, what the creditors and the international community are looking at, “especially in the finance sector, is how we will bring it down to the 30 percent level. The 30 percent is the target,” said the senator, referencing the record low of 39.60 percent debt-to-GDP ratio in 2019, a year before the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, there is no benchmark for the right debt-to-GDP ratio. “The typical number for a developing nation like us is about 60 percent. But that’s not (set) in stone,” Gatchalian said.

“So, we borrowed to respond to that pandemic. It stayed at that level of 60 percent debt-to-GDP. The reason why we didn’t go up to that is because of that understanding that developing nations should not go beyond the 60 percent level. Anything beyond that is considered red alert, sounding the alarm bells,” he said.

The total national debt stands at P15.48 trillion, while the debt-to-GDP ratio reached 60.9 percent (as of June 30).

Fiscal consolidation plan

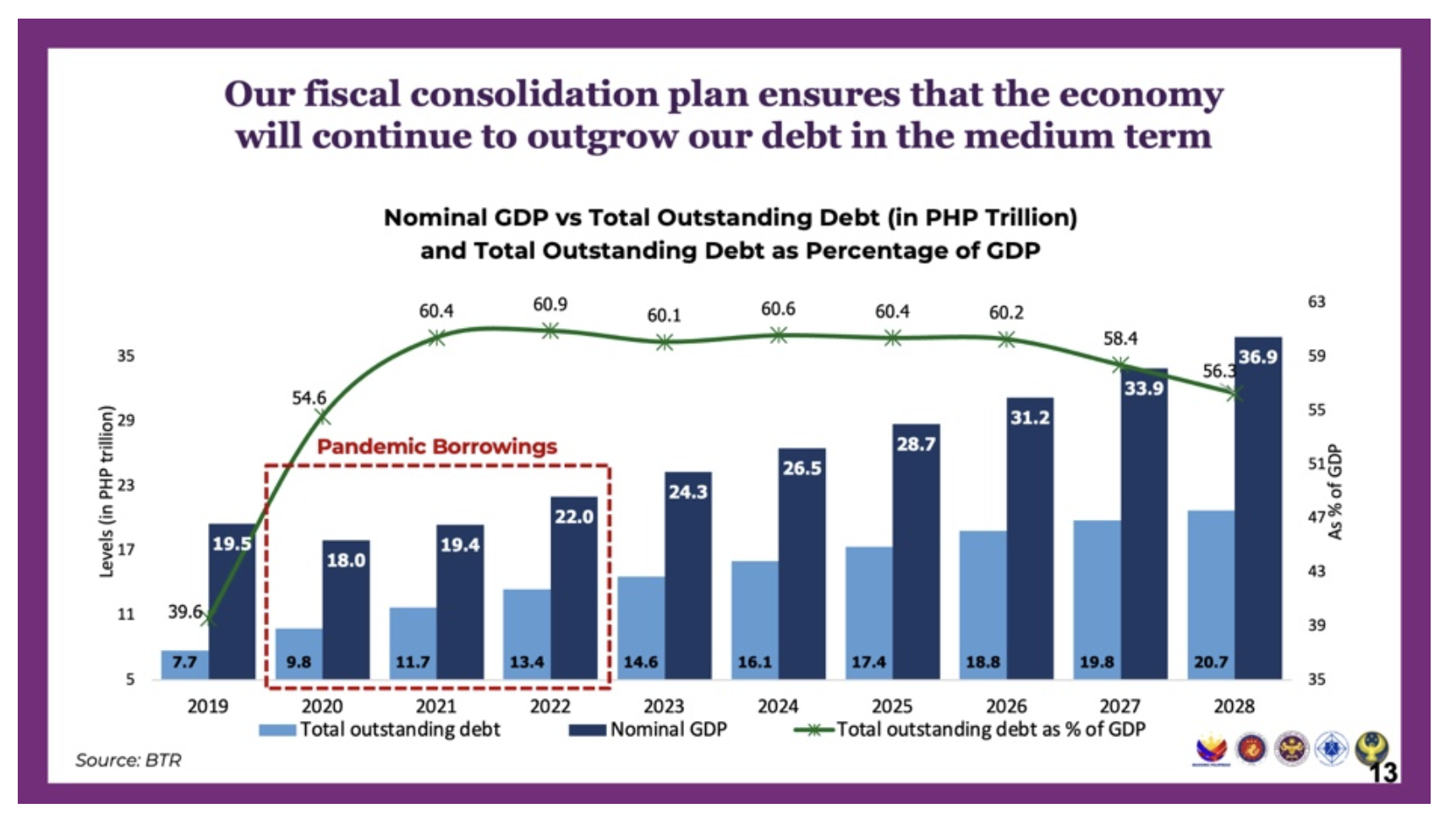

The Marcos economic managers have decided to maintain a 60 percent ratio between the outstanding national debt and GDP from 2022 to 2026. It will gradually go down, reaching 58.4 percent in 2027 and 56.3 percent in 2028 (see chart above).

However, for this debt-to-GDP ratio to be sustainable, the economy must continue to grow by 6-7 percent annually until the end of President Ferdinand Marcos’s term in 2028. Economic managers predict that the debt stock will increase to P20.7 trillion by that time. This doesn’t worry Finance Secretary Ralph Recto, assuring lawmakers that the economy can outgrow the pace of borrowings, as the nominal GDP is projected to be worth P36.9 trillion by 2028.

The Bureau of Treasury’s optimistic projections, which have been echoed by Recto, indicate that the fiscal consolidation plan will lead to a lower debt level—a debt-to-GDP ratio of 56.3 percent in 2028 from the current 60.9 percent (as of end-June). The government plans to reduce this ratio even further to 60.6 percent by the end of this year.

Recto and other economic managers who are part of the Development Budget Coordination Committee (DBCC) had a meeting with the Senate two weeks ago. The Senate is holding parallel hearings on the budget while waiting for the House of Representatives to pass the budget bill.

At the DBCC briefing, Recto said that the fiscal consolidation plan, which is the policy of reducing debt accumulation and deficits, “ensures that the economy will continue to outgrow our debt in the medium term.”

Legislated framework

The MTFF is a legislated framework for the comprehensive fiscal strategy during the entire term of the Marcos administration. Budget Secretary Amenah Pangandaman has described it as the roadmap for the administration’s “Agenda for Prosperity.”

In a statement dated Sept. 20, 2022, the budget chief enumerated the country’s economic objectives listed in the framework: achieving 6.5 to 7.5 percent real GDP growth in 2022; 9 percent or single digit poverty rate by 2028; 3 percent national government deficit to GDP ratio by 2028, and less than 60 percent national government debt-to-GDP ratio by 2025.

“It is with these objectives in mind that we have designed our National Expenditure Program (NEP),” she said.

Pangandaman, who chairs the DBCC, said that the MTFF would guide the government’s legislative agenda. She thanked Congress for “recognizing the importance of a fiscal consolidation and resource mobilization plan, including measures such as rightsizing government structures and personnel.”

Revised assumptions, targets

But on April 4, 2024, the DBCC decided to recalibrate the government’s medium-term macroeconomic assumptions, fiscal program, and growth targets for 2024 to 2028 so that they can reflect the prevailing domestic and global developments. “This recalibration will ensure that the government’s targets respond more directly to the needs of the Filipino people and that strategic growth-enhancing fiscal consolidation is being pursued for sustainable and inclusive development,” said the DBCC in a statement.

On the debt stock, the DBCC explained that “borrowings will be complemented by an upsurge in revenue collections over the medium term as a result of improved tax administration and recalibrated revenue measures. This will ultimately allow taxpayers such as consumers and businesses to have more headroom to spend out of their income.”

With this, the debt-to-GDP ratio “will also decline from 60.2 percent in 2023 before settling at 55.9 percent in 2028, well within the internationally accepted threshold of 70 percent, as recommended by the IMF (International Monetary Fund).”

Justifying the postponement of the original plan to reduce borrowings starting this year, the DBCC explained that these fiscal targets “reflect the DBCC’s commitment to balancing the requirements of supporting economic growth while ensuring prudent fiscal management by keeping the country’s debt profile in the median of comparable countries in the ASEAN, among peers with similar credit rating, and other emerging market economies.”

Singling out debt reduction, Gatchalian explained to the INQUIRER that the legislated framework has become the target for how the government will reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio. He conceded that MTFF, which has become a law, “gives the Department of Finance and the economic team the flexibility to adjust, but it should serve as a target for the government to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio because that’s already the target.”

Fiscal buffer

Gatchalian said that global economic shocks such as the Russia-Ukraine War led to increases in oil prices, prompting the DBCC to adjust its economic targets. For instance, he recalled that the original target was for the debt-to-GDP ratio to go below 60 at 58.3 percent by 2025, but the government decided to maintain it at 60.4 percent.

“So, in other words, it’s elevated until 2026. I hope nothing bad happens,” said the senator, citing as an example the mpox outbreak that was declared a public health emergency of international concern by the World Health Organization last Aug. 14.

“If this mpox goes out of hand, then we are at the maximum already. We are in the danger zone because we’re at a high level. So, my point (is), granted that there are external factors that warranted the adjustment of the targets, but we should not adjust the targets easily because the targets are meant to give us back that buffer that we enjoyed prior to the pandemic. Because that buffer saved us.”

Gatchalian said that prolonging the elevated debt-to-GDP ratio above the 60-percent threshold could put the country “at the brink of danger.”

“Because anything that happens, for example, there’s a war in the region, then we’re in trouble because we don’t have the buffer anymore. So, we should bring back the buffer because that saved us. One lesson about the pandemic in terms of fiscal management: that buffer saved us, and right now we’re not in that situation,” the senator stressed.

What he meant by buffer was to return to the record low of 39.60 percent debt-to-GDP ratio in 2019, when the country’s GDP rose to 6.0 percent.

Pandemic borrowings

When the pandemic hit in 2020, GDP contracted by 9.5 percent, the worst economic performance of the Philippine economy in the post-World War II era, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority. The pandemic forced the Duterte administration to resort to borrowings to pay for vaccines and personal protective equipment for medical personnel, as well as to capacitate hospitals, and assist businesses that were struggling with lockdown measures to contain the spread of the coronavirus.

“So. if you’re tax collection went down, your only source of funds will be borrowing again. But because we managed our debt for a very long time at 30 percent we had that buffer, so the government used that,” said the senator.

Gatchalian, who was the chair of the Senate Economic Affairs Committee from 2016 to 2019, recalled that the pre-pandemic debt-to-GDP ratio was a “very healthy level” because it gave the Duterte administration the fiscal flexibility to borrow more.

“The reason for that is we want to keep ourselves at that (2019) level so that in any aberration, for instance, pandemic, wars, financial crisis, we have that buffer to use, to borrow … in order to have a shock absorber for that aberration. So, that 30 percent (level) is a very healthy stage,” he said.

The goal of returning to the 30-percent level is important for the Philippines as it is still a developing nation. However, it took three successive administrations to reduce the ballooning debt. The all-time high debt-to-GDP ratio of 74.90 percent was reached in 1992, under President Fidel Ramos, according to Trading Economics data.

The same data showed that President Gloria Arroyo was able to drop the debt-to-GDP ratio from as high as 71.4 percent in 2003 to 54.8 percent by 2009. Under the Benigno Aquino presidency, the ratio was 52.4 percent in 2010 but it went down to 44.7 percent in 2015.

From 42.1 percent in 2016, President Rodrigo Duterte managed to further bring it down to 39.6 percent in 2019 (before it climbed again to 54.6 percent in 2020, during the pandemic, and 60.4 percent in 2021). Since 2022, the percentage has remained at the 60-percent level under the Marcos administration.

Read more: Maturing COVID loans push PH debt to limit: Did we benefit?

Refinancing the large borrowings

Recto admitted during the DBCC briefing that the pandemic borrowings inherited from the Duterte administration were the cause of the increased debt servicing under the Marcos administration.

In 2019, when the country achieved its lowest debt-to-GDP ratio at 39.60 percent, the total nominal debt was only P7.7 trillion.

“But this figure nearly doubled to around 13.4 trillion pesos right after the pandemic, just as the Marcos, Jr. administration took over. And because of all these geopolitical tensions, the cost of our borrowings has climbed post-pandemic as central banks have raised their interest rates to combat inflation,” Recto said. “Therefore, we are now refinancing the large borrowings contracted during the low-interest rate period in 2020 to 2022 with new debts that bear higher interest rates. This is the reason why our interest payments for next year are higher by around 11 percent,” he said.

According to the finance chief, while interest rates have gone up, the cost of borrowing remains manageable and much lower than the GDP growth. “In fact, our effective interest rate for next year is only 5.3 percent, which is very cheap considering that the average term of our debt is 7.5 years,” he said.

Recto recalled that when he became finance secretary in January this year, his first priority was “to recalibrate the country’s growth and fiscal targets to ensure that they are achievable and adaptable to external shocks.”

“Our refined Medium-Term Fiscal Program reduces our deficit and debt gradually in a realistic manner; while creating more jobs, increasing our people’s incomes, and decreasing poverty in the process. And under this, we have ensured that every peso to be collected or borrowed will be stretched to deliver the biggest bang per buck for the Filipino people,” he said, and added: “And we continue to manage our debt according to the highest standards of fiscal discipline. As we are very vigilant not to max out the Philippine national credit card.”

Outgrowing debt

To put it simply, managing debt requires the economy to grow steadily, with 6-7 percent GDP growth for the next four years, to keep up with the rate of borrowing.

“The strategy of the administration even the past, during President Duterte, is to outgrow debt, meaning we grow faster and once we are growing faster, we don’t grow debt as fast, so that we outgrow debt. So, the forecast is about 6 to 7 percent. As long we grow between 6 to 7 percent, we can outgrow debt,” said Gatchalian.

At this pace of economic growth, he expects the debt-to-GDP ratio to start slowing down significantly beginning in 2026.

For every 1 percent of real GDP growth, the government will earn additional P34.1 billion in revenues. Thus, if the country continues to grow by at least 6 percent in the medium-term, it will generate substantial revenues of at least P204.6 billion to strengthen its capacity to manage and pay existing and future debts, according to a briefer provided to the INQUIRER by the senator.

Asked what the government can do to lessen borrowing, Gatchalian said: “We borrow to spend, but we cannot lessen spending because there are a lot of needs. But we can spend judiciously and wisely. That’s what is important now. Let’s make sure that we are spending wisely, judiciously and efficiently.”

Take a look at the first and second parts of this special report.