152 acres of stories: Manila’s silent city of heroes

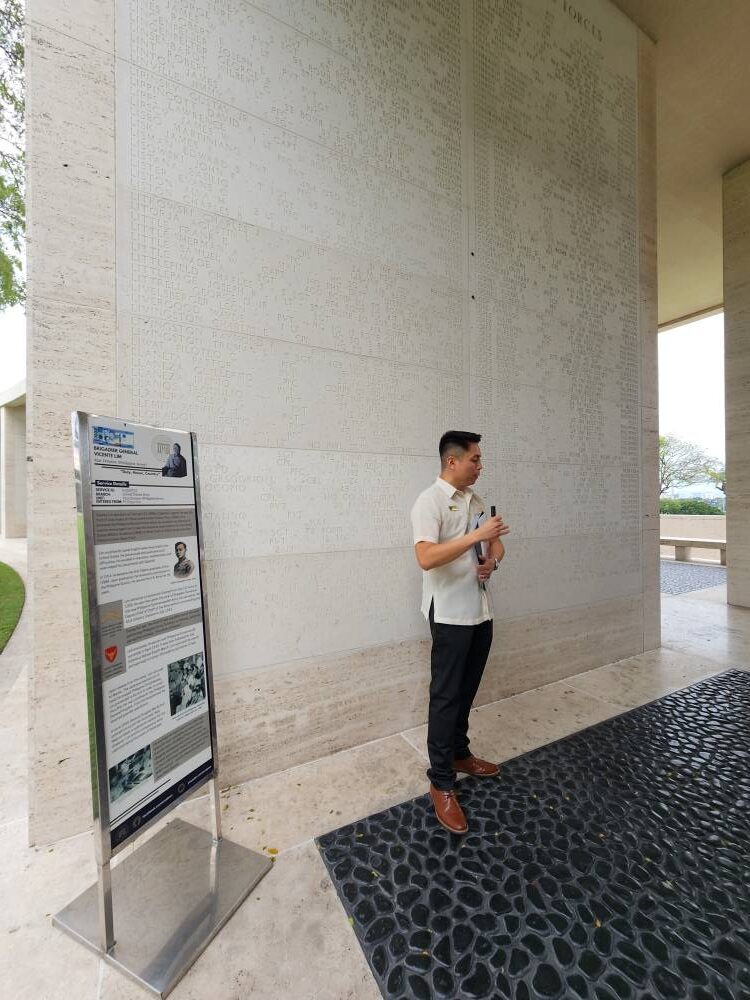

Vicente Lim IV, director of the Manila American Cemetery Visitor Center, stood before the Wall of the Missing. Behind him, engraved on the wall, was the name of his great-grandfather—Brig. Gen. Vicente Lim.

The older Lim was the first Filipino to graduate from West Point. He fought in World War II, leading the 41st Division, which became known for its tenacity and bravery, earning them the moniker “Rock of Bataan.”

In June 1944, while on his way to join Gen. Douglas MacArthur in Australia, Lim and his companions were intercepted and captured by Japanese forces. He was imprisoned in Fort Santiago and later transferred to the Old Bilibid Prison. Reports say he was beheaded, but his body was never found.

At one point, General Lim was honored on the P1,000 bill alongside Josefa Llanes Escoda and Jose Abad Santos. While his image is no longer on the currency, his name remains forever etched in the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial in Global City, Taguig. There, his memory is preserved, and his story continues to be told.

But his is just one of the 50,000 stories waiting to be discovered, according to his great-grandson.

“We do a lot of research into individual stories. We try to dig up photographs, letters, or anything that fits within a theme we want to tell,” Lim said. The stories are personalized depending on the guides, who research subjects that either relate to them or resonate with them.

The cemetery is the largest managed by the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC), with around 17,000 burials on-site. Despite its name, not everyone buried here is American.

“When you walk across these meticulously maintained grounds, you have to remember that you’re walking on the shoulders of heroes. And they’re buried here side by side, without regard for race, creed, religion, or nationality. Filipinos lie beside their American comrades in arms,” Lim said.

More than graves

This means that crosses stand next to Stars of David, and a private rests beside a general. The uniformity and equality serve as a statement: Everyone buried here gave everything they had for freedom.

Even the greenery that thrives across the cemetery’s 152 acres tells the stories of the heroes buried there.

“We can’t just replace any plant, shrub, tree, or flower with another. It has to be the exact same one. The plants you see here are representative of at least one Pacific battlefield. Of course, mangoes are better here, but India is represented by the mango trees we have in another part of the cemetery,” he explained.

At any point in the year, at least one flowering shrub or plant is in bloom, a perpetual cycle of remembrance. Lim noted that summer is the most beautiful season, as more flowers blossom across the grounds.

The cemetery is open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. They take “every day” seriously, closing only twice a year—on Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. Guided tours are free, and visitors can participate in the flag-lowering ceremony at 4:45 p.m.

For those who prefer to explore at their own pace, stops with QR codes provide details about the heroes buried there. However, Lim encourages visitors to start with a guided tour. The map sections in the memorial are best experienced with an expert who can share the deeper stories behind the events depicted on the walls.

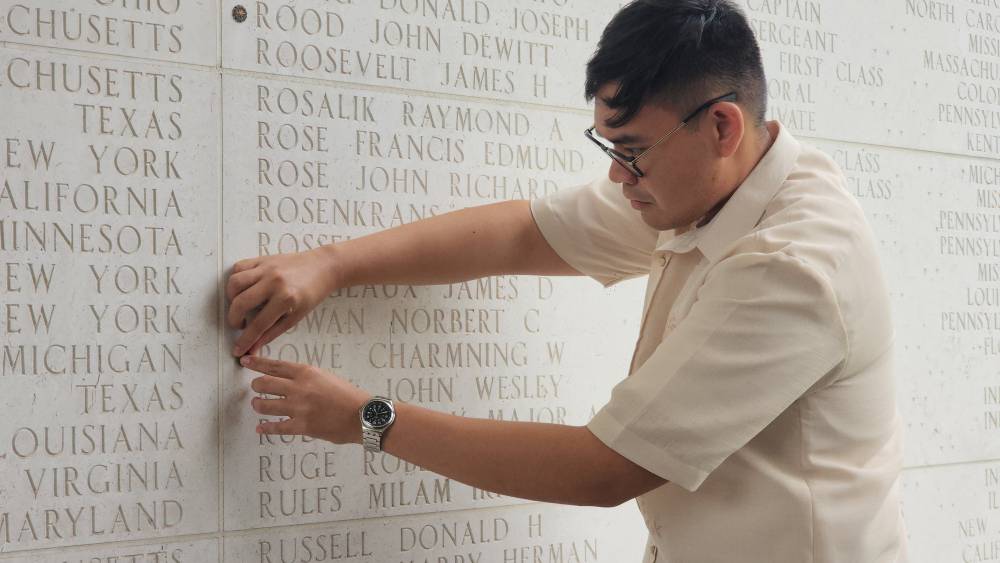

It is a breathtakingly serene place. If you pause here, you will only hear your own breathing, the rustling leaves and the birds singing. On certain days, you may witness a solemn ceremony: the moment when a rosette is bestowed next to a name. The rosette signifies that a missing person has been found, just as Private Charmning Rowe was on our visit.

US Ambassador MaryKay Carlson noted that the cemetery is the first place they take house guests to.

“It shows the shared history, the shared sacrifice of Americans and Filipinos who fought for our freedoms,” she said.

Visual accounts

On Feb. 13, Carlson was there to open the exhibit “Liberation of Manila: 80 Years of Remembrance through Art,” where four artworks were loaned to ABMC by the National Museum of the Philippines (NMP) until Feb. 25.

The paintings depict the destruction of Manila’s landmarks during the war. NMP director general Jeremy Barns emphasized their historical significance: “These are not just works of art; they are historical visual accounts made, as far as we know, firsthand by the artists—Fernando Amorsolo, Diosdado Lorenzo, Nena Saguil, and Galo Ocampo—during this period of war in Manila and its aftermath, from the 1942 bombing of Intramuros and other parts of Manila to the postwar years in the late ’40s.”

Amorsolo painted the “Burning of Sto. Domingo,” Ocampo did “Ruins of the Legislative Building,” Lorenzo depicted “Ruins of Sales Street, Quiapo,” and Saguil painted “Ruined Gate of Fort Santiago.”

“In just one month, the city was reduced to rubble, its people caught in unimaginable suffering, and its legacy forever scarred. Sadly, most people don’t know about this battle. As we mark the 80th anniversary of this tragedy, our goal throughout the past year has been to ensure that this milestone is recognized with the weight and solemnity it deserves,” said ABMC superintendent Ryan Blum.

Many of these buildings have been rebuilt and can still be visited today. The Legislative Building now houses the National Museum of Fine Arts. Sales Street has once again become a bustling area, and Fort Santiago still stands strong.

Sto. Domingo Church was relocated to Quezon City. In Amorsolo’s painting, a statue of Miguel de Benavides stands prominently. He was the third archbishop of Manila and founder of the University of Santo Tomas (UST). The same statue can be found in front of UST’s Main Building. There’s a replica where it once stood in Intramuros.

During the war, UST served as an internment camp for 4,000 civilians. Some of those who did not survive are buried in Taguig, their stories commemorated on a panel in the Visitor Center.

“It was once a battlefield, its streets bearing witness to both the horrors of war and the triumph of the human spirit,” Carlson said. “Through unimaginable loss 80 years ago, Manila and its people emerged with a resilience that endures to this day.”

For Lim, remembering also means having hope for a better future.