A farmer, a fisherman, and a chef walk into a kitchen . . .

If there’s one way to describe Terra Madre Visayas, it is this: it reintroduces Philippine ingredients to Filipinos and foreign chefs. It’s almost like a courtship ritual among farmers, fisherfolk, and chefs.

How do you make use of what’s growing in our land and what we catch in the sea to create a dish? It’s not even about inventing a new dish, although that is welcomed and celebrated at the event as well. It’s about adapting to what’s available.

This was the theme of the recent event held in Bacolod, including the dinner created by the Roots team of Siargao at the Lanai restaurant. The group of chefs made use of what they could find in Negros to create dishes they grew up with. They had members who hail from Italy, Spain, Mexico, and the Netherlands. One of the ingenious things they did was create a substitute for olive oil using ampalaya.

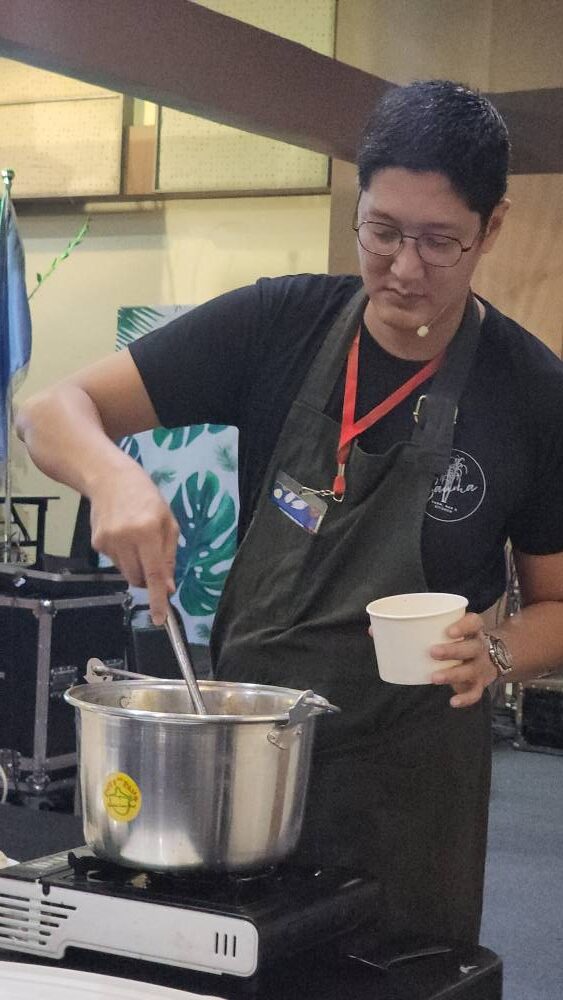

We spotted Lifestyle’s own Angelo Comsti purchasing ingredients for his adobo from the festival grounds of Terra Madre Visayas, where fresh produce was available daily. He made his version with batwan vinegar and batwan fruits. People often think of batwan when they make or eat kadyos, baboy, langka (KBL). Using batwan for something other than what it is famous for is the point. He presented his adobo after his talk at the Negros Residences Hall.

Terra Madre is a network of food communities that pushes for food production that protects the environment and communities. Behind this effort is the Slow Food Movement, which advocates for good, clean, and fair food for all.

This vision was translated into a street full of organic food stalls from all over Panay Islands. North Capitol Road was converted into a marketplace for fresh produce, dry ingredients, and condiments. Some of our finds included mulberries that randomly popped up in the stalls, an abundance of batwan and takway, and dried fish from Cadiz. But the pinindang from Antique was probably one of the best discoveries of the week. Pinindang is a cluster of small dried anchovies. It melts in the mouth after being fried crisp.

The Slow Food Movement had its own spot at the end of the market, where dishes, drinks, and desserts could be enjoyed on the spot. This included grilled eel from Bago City, sea urchin roe from Sagay, and kulabo crepe cake from Lambunao, Iloilo. Kulabo is young coconut meat. There was a bar that served cocktails, including Minoyan Sling, which was made of vodka, kamias, barako, and topped with a burnt bay leaf.

The vibe was very relaxed and jovial. The word “chef” often had a sophisticated ring to it.

Communal dining

But at Terra Madre Visayas, chefs from all over the Philippines ordered the same food as you did. You ate with them at the same monobloc table, introducing yourselves between spoonfuls and chatting about food. The festival ground was made up of curious people who wanted to give undiscovered gems a try.

At the Negros Residences, speakers, including chefs, breeders, and farmers from all over the country, shared their expertise on various topics. One of the most interesting sessions we attended was by University of the Philippines professor Raymond Macapagal, who discussed the “Power of Sourness.”

Macapagal shared how our bodies are built to reject sour flavors, but Filipinos are trained to enjoy sour food from a young age. We like our sinigang, unripe mangoes, and sour citruses. He also shared how, in some places, we balance sour fruits by dipping them in vinegar.

The workshops and talks were multilingual. They were in English, Filipino, and even Hiligaynon.

On Nov. 21, Tourism Secretary Christina Garcia-Frasco committed the support of the Department of Tourism to Terra Madre Asia Pacific, which will be held next year in the city. Local officials, including Negros Occidental Gov. Eugenio Jose Lacson and Bacolod Mayor Alfredo Benitez, likewise committed their continuous support to the Slow Food Movement and Terra Madre.

The Slow Food Movement started in Negros Occidental in 2010, spearheaded by a group that included Ramon Uy Jr., Southeast Asia Slow Food councilor. The movement had grown significantly since then but they set their sights further.

“We’re very happy, but we know that we’re not yet finished. We’re still growing,” he said. They will set up a hub for Southeast Asia, where other countries can come and learn how the region did it.