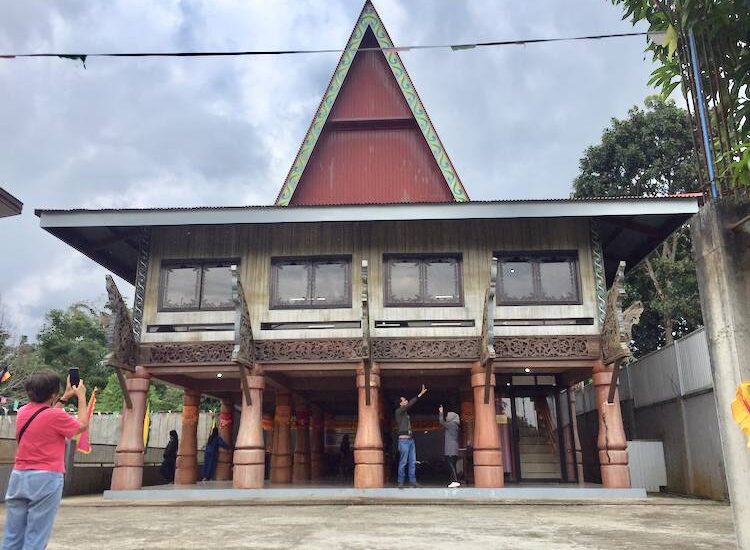

A new landmark rises in Marawi

As Marawi is slowly but surely rising from the tragedy of the 2017 siege, a new landmark rooted in Maranao culture and heritage rises in the city known for its cool weather and Islamic character.

As an adaptation to change of various kinds, the Dayawan Torogan in Barangay Dayawan has been reincarnated to become a cultural center where family meetings and Islamic seminars are held.

It is also some sort of a lifestyle museum, where the life of the Maranao nobility and daily life are presented through a setup featuring undivided bedrooms, a section for the musical instrument kulintang, loom weaving, and shell inlaid baors (wooden chests).

Inaugurated in August last year, this new torogan was built from 2020 to 2022 with funding from the local government of the city through Mayor Majul Gandamra. The torogan, which literally means “a place to sleep,” is the large house of a datu in Maranao society.

Typically, there is one torogan in every agama or village, but very few of these structures remain to this day.

Perhaps the creme de la creme of Philippine indigenous domicile architecture, a torogan is a one-story wooden edifice with a steep gabled roof, traditionally of cogon, and posts made from large tree trunks resting on stones to avoid damage in the event of an earthquake.

Its walls are made of wooden planks, and the floor from a type of wood called barimbingan.

Artistically, the most important parts of the house are the panolong or wing-like house beams jutting out of the façade, the carved panels inside and outside of the house, and the central beam called tinai a walai (house intestines).

All designed in okir, the panolong are carved with pako rabong (fern) or naga (serpent) motif, while the beams are polychromed with Maranao traditional colors of green, yellow, red, and white.

Old Dayawan Torogan

The old torogan was first built from bamboo and nipa by Sultan Boowa Ayop in the 18th century and was reconstructed by Sultan Conding Arindig and Datu Cotawato Maguindanao, together with their siblings and relatives, in the late 19th century.

This 19th-century house was located on land measuring 12 by 15 meters, with a floor area of 120 square meters. In a decrepit state, it was abandoned by the family of the sultan living there some time in the late 1950s.

It was, however, rebuilt and reconstructed at an adjacent lot by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and Mindanao State University (MSU) in the 1990s. Dr. Abdullah Madale, former MSU official and educator, was the one who initiated the restoration.

Local artisans were employed in restoring the posts, wooden panels, and carvings and the overall reconstruction of the house.

The family and the National Museum agreed in a verbal statement that the house would serve as a living museum showcasing the culture and heritage of the Maranaos. It is, however, not clear if this deal pushed through or was sustained.

Historic site

This torogan is a historic site, as it is said that this was where the Dansalan Declaration of 1935 was signed by the Maranao datus who were resisting being included in the Republic of the Philippines.

The new torogan was built on the lot at the back of the old one. The large wooden posts, walls, and floor were replaced with concrete while the windows are now made of sliding glass. The roof is made from galvanized iron sheets.

The panolong from the old torogan were reinstalled, along with various carved wooden panels and the central beam. Stored inside are heirloom pieces such as baors inlaid with shells, earthenware vessels, and food trays called talam.

According to the local government, the torogan’s reconstruction is dedicated to the residents of Dayawan “in preservation of the Maranao culture and heritage.”